4th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 13 :: Anthony Cappo on William Blake

I.

When I first read William Blake in a Romantic Poetry class my junior year of college, it set off immediate shockwaves. I had read the Beats and knew that they were big Blake fans, but had never read any of his work. Blake’s is a voice of freedom. A voice that smashes hypocrisies, injustice, and sexual repression. A voice I never heard growing up.

Poetry, literature, and the arts in general, were not things that were discussed in my house growing up. Writers and artists were “weirdos” and “freaks.” They were the hippies, the people who hung out on South Street in Philadelphia, the theater workshop types. Any expressed desire to pursue a career in the arts was met with the question, “How are you going to make any money doing that?”

We were conservative and Catholic. My dad was in favor of Frank Rizzo, Richard Nixon and the Vietnam War. Any contrary opinion would not have a long airing at our dinner table.

Every Sunday, my parents, my four sisters, and I would put on our best and head to church. We paraded down the aisle to our seats and everything looked spiffy and perfect. We weren’t Bible-thumpers, but priests and the moral teachings of the Church were not seriously questioned. I attended weekly CCD classes throughout elementary school so that I could receive the sacraments. Stern priests enforced order and guided religious learning.

This whole creaky edifice came toppling down when my parents split up soon after my 13th birthday. All Commandments were not followed in my parents’ marriage and now my father was living with the woman who would eventually become his second wife. All of a sudden, the certainties had evaporated—we didn’t all gather for church Sunday mornings, the values that once seemed so sacred were not anymore, home finances cratered and spiraled further down.

My parents’ divorce was not a one-and-done event. For years afterwards, throughout my adolescence and young adulthood, there was constant tumult. This mishegoss was caused, mostly, by the borderline antics of my father’s second wife and my mother’s and sisters’ inability to not let her get the best of them.

II.

Into all this stepped Blake. A man who heard and spoke to angels, who sat around naked with his wife in his garden and read Paradise Lost, who sharply questioned the religion, politics and morality of his time. A man who, to my twentieth century eyes, looked conservative enough to be one of my uncles!

But conservative he was not. I was angry and questioned everything. In Blake, I found a kindred spirit. His cry for social justice and puncturing of hypocrisy spoke to me.

The poem, “The Chimney Sweeper,” resonated with me. In Blake’s England, little children as young as six years old, either orphaned or sold into brutal apprenticeships by their parents, were used to clean soot from chimneys. Their lives and work were extremely hard and often resulted in painful injuries, death on the job, or early deaths in their teens or twenties from the work’s toll. But the society seems to have weighed the need for clean chimneys over the awful costs to the children in blighted bodies, shortened lives, and shattered innocence. Here is the poem, in its entirety:

[box]The Chimney Sweeper

A little black thing among the snow

Crying ‘weep, ‘weep, in notes of woe!

Where are thy father & mother? say?

They are both gone up to the church to pray.

Because I was happy upon the heath,

and smil’d among the winter’s snow;

They clothed me in the clothes of death,

And taught me to sing the notes of woe.

And because I am happy, & dance & sing,

They think they have done me no injury,

And are gone to praise God & his Priest & King,

Who make a heaven of our misery.

[/box]

Blake gives the chimney sweeper his voice. Innocence destroyed while the sweeper’s parents satisfy themselves that they are doing the right thing. The sweeper’s labor eases the way for the pillars of society and this is alright with their God.

The parents’ reaction echoes what slavery defenders said during the same time period: they choose to mistake the sweeper’s heroic efforts to keep some joy in his life, especially through song, as evidence that he is happy with his lot in life. And so the parents’ (and slaveholders’) guilt is assuaged, because—look!—how happy they are.

Blake found further fault with the Church and organized religion in “The Garden of Love”:

[box]

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And “Thou shalt not” writ over the door;

So I turn’d to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore,

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be;

And Priests in black gowns were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars my joys & desires.

[/box]

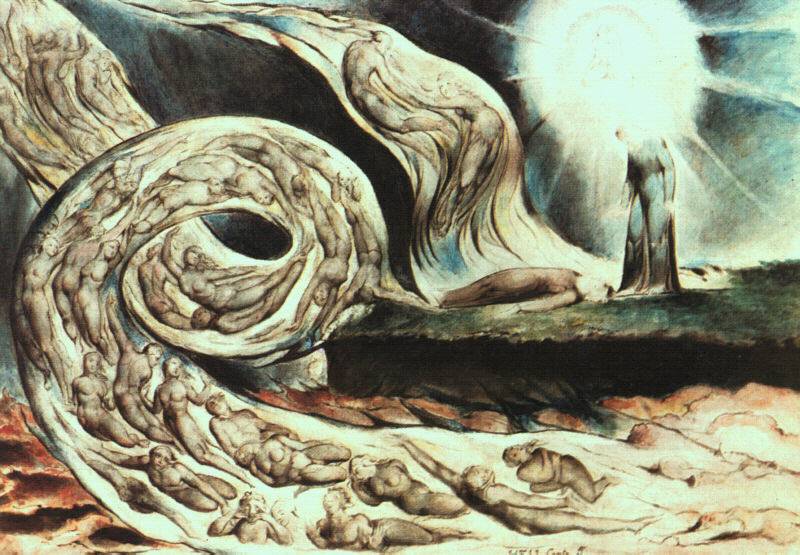

[textwrap_image align=”right”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/blakegardenoflove.jpg[/textwrap_image]For me, this poem was a freedom text. A celebration of sex and the body, and a rejection of repressive, and false moral rules. Emblems of death and repression replacing flowers, and dour priests enforcing their stern rules and killing all joy, sex, and expression. When I read this poem, I always think of the priests at CCD and at Church, and how repressive (and repressed) they always seemed.

And the last two lines are so powerful. The spondee of “black gowns” breaks up the iambic flow, liked a raised hand putting an end to all fun. The internal rhyme is memorable and impeccable. These lines always remained with me, a testament to the power of words and, especially, poetry.

Blake returns to the themes of sex and repression in “The Sick Rose”:

[box]

O Rose, thou art sick.

The invisible worm

That flies in the night

In the howling storm

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy,

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

[/box]

Again, for a twenty-something who came from a fairly repressed background, this was explosive stuff. The obvious sexual imagery, and hints of passion and lost innocence rung something in me. I can’t claim to fully understand this poem, but, like in “The Garden of Love,” an outside force destroys the more innocent “crimson joy” of the rose. Its arresting images and turbulent sexuality helped stoke a love for poetry and the ability of words to create such a powerful canvas.

Blake’s effectiveness with relatively simple language has been a major influence on my writing. In his lyric poems, Blake does not try to obscure or create unnecessary barriers with the words or syntax he chooses. Virtually anyone can “understand” Blake’s lyric poems. But Blake makes them memorable and he makes them sing. And he does it economically—not even close to a wasted word. These poems are from Blake’s “Songs of Experience” and they are songs in every way.

Blake, too, had a keen grasp of human psychology, as shown in “A Poison Tree.”

[box]

I was angry with my friend:

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow.

And I watered it in fears,

Night & morning with my tears;

And I sunned it with smiles,

And with soft deceitful wiles.

And it grew both day and night,

Till it bore an apple bright.

And my foe beheld it shine,

And he knew that it was mine,

And into my garden stole,

When the night had veild the pole;

In the morning glad I see

My foe outstretchd beneath the tree.

[/box]

That first stanza has always blown me away. So simple, yet so true. A psychological guide for sustaining friendships and relationships. And the wonderful image of the unexpressed anger, encased with layers of deceit, morphing into a deadly apple. I came back to this poem more than once in my twenties, thirties and forties. It has always contained an essential truth for me.

Blake returns to this theme of unexpressed feelings, though this time in the romantic context, in “The Angel.” Here, the speaker dreams she has an angel beside her, who comforts her and dries her tears. But she does not tell him how she feels about him and “hid from him her heart’s delight.”

[box]

So he took his wings, and fled;

Then the morn blushed rosy red.

I dried my tears, and armed my fears

With ten thousand shields and spears.

Soon my Angel came again;

I was armed, he came in vain;

For the time of youth was fled,

And grey hairs were on my head.

[/box]

Again, Blake urges full expression of feelings, a kind of romantic carpe diem. Here the speaker does not express her feelings, is left, arms herself against further hurt, and when the angel returns not only is she now unreachable, but is also old and the time for love has fled.

III.

After college, I did not further my English education as a teacher or graduate student. Although I wrote poetry in college, I did not apply to an MFA program. (In fact, at that point in my life, I had never heard of an MFA program.) No, after taking a year off to think things over, I went to law school, and, although many fibers of my being resisted it, finished, and began a two-decade plus legal career. I wrote very little poetry for most of the next two decades.

As you can imagine this was a very demanding—and not altogether satisfying—career path. It was hard to keep a toe in poetry. But when I needed a reminder of my other self, my better self, I often turned to Blake. During this long Babylonian Exile, I found myself reaching most for Blake’s “Marriage of Heaven and Hell,” and its indispensable Proverbs of Hell.

The “Marriage of Heaven and Hell” contains many of the themes in the “Songs of Experience” poems that I liked so much: full expression of feelings and desires, celebration of creativity, and suspicion of priests and organized religion. This long poem contains a number of prose passages and, in the middle, what Blake calls The Proverbs of Hell.

Blake turns on their head the usual associations with Heaven and Hell. For Blake, Heaven is rules, laws, repression; Hell is energy, passion and creativity. The Proverbs of Hell are Blake’s imagining of the sayings of a people governed by these qualities.

During the years when I was not writing, I would turn to these Proverbs almost as Holy Scripture. In my dark legal wood, they were beacons of light, a reminder of when I myself was governed by energy, passion and creativity. They helped keep the pilot light on when the winds were howling.

The proverbs that moved me most can probably be divided into a handful of categories. Those that dealt with full expression of desires and feelings; celebration of creativity; suspicion of priests and organized religion; and general proverbs for living. “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” is worth many a read and re-read, but I’ll just leave with a couple of my favorites.

[articlequote]Expression of Desires and Feelings:

Exuberance is Beauty.

The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.

He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence.

The lust of the goat is the bounty of God.

You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.

Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires.

Celebration of Creativity:

Improvement makes strait roads, but the crooked roads without

Improvement are roads of Genius.

To create a little flower is the labor of ages.

Eternity is in love with the productions of time.

Suspicion of Priests and Organized Religion:

As the caterpiller chooses the fairest leaves to lay her eggs on, so the priest

lays his curse on the fairest joys.

Prisons are built with stones of Law, Brothels with bricks of Religion.

General Proverbs for Living:

Listen to the fool’s reproach! it is a kingly title!

The eagle never lost so much time as when he submitted to learn of the crow.

He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star.

As the air to a bird or the sea to a fish, so is contempt to the contemptible.

[/articlequote]

[line][line]

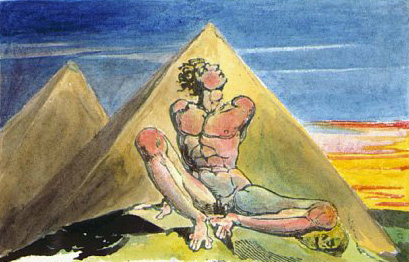

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/P10004891-e1428936841140.jpg[/textwrap_image]Anthony Cappo’s poems have appeared in Connotation Press – An Online Artifact, Stone Highway Review, The Boiler Journal, Yes Poetry, Lyre Lyre, and other publications. He received his M.F.A in creative writing from Sarah Lawrence College. Anthony lives in New York City, where he can be found singing through the streets and subway stations. He’ll be joining us, talking about his love for Blake as part of 30/30/30 LIVE! :: GROUP HUG at Mental Marginalia on 4/28.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]