4th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 16 :: Catherine Bull on Rimbaud …and Rambo

I’m not much for debauch, not much for rude rebellion, I don’t speak French. I don’t take inspiration from Rimbaud’s words, his visions, his attitude, or his life story. He’s never been a haven or a guiding light the way you usually mean when you say a poet’s had a huge impact on your work, this enfant terrible who galavanted about farting on the literary society he wanted to impress with the by turns murderous and cooing Verlaine; this symbolist poet who broke open free verse, the prose poem, the first person personification of inanimate objects, and synesthesia; this thoroughly debauched visionary who dropped the mic at 18 and wound up an ascetic merchant in Abyssynia writing nothing but boring, cranky letters home to his mom and then croaked at 37; this poet of poets who inspired all those 20th century biggies—the Bob Dylans, the Patti Smiths, the Surrealists, the John Ashberys, the Jim Morrisons—this figure upon whom my gaze remained fixed for years—well he would never make my desert island list.

[articlequote]When I was sixteen,” says Patti Smith, “my salvation and respite from my dismal surroundings was a battered copy of Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations.” [/articlequote]

That wasn’t my Rimbaud experience.

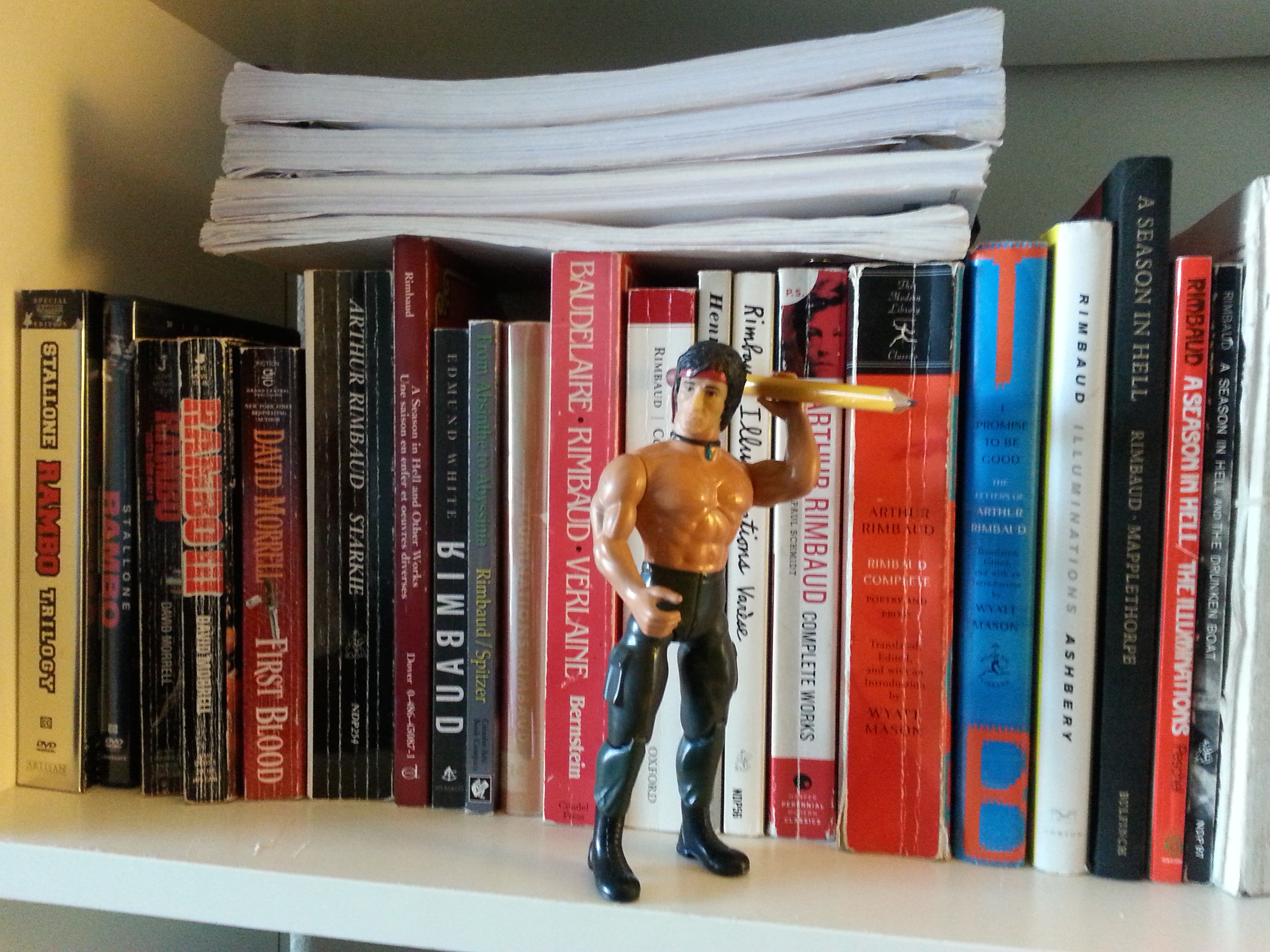

Although I did read almost all the biographies in English and a big bite of the translations. (I can’t say I’ve read them all, since everyone and their mother translates Rimbaud, but I have read three Completes cover to cover and more than a few different Drunken Boats, Illuminations, and Season in Hells.)

[articlequote]Rimbaud seemed to me a kind of mirror,” says translator Paul Schmidt, “I set myself the task of entering his strange world as I perceived it; to seek his path even where the wind at his heels had effaced it. I came at last to see his poems as incidents in a life that we—he and I—somehow, somewhere, shared. […] I soon found no way within me or without to separate his voice from mine, nor did I want to.” [/articlequote]

That wasn’t my Rimbaud experience either.

Although I did spend the better part of three years writing (attempting) close to forty poems riffing off, relating to, or starring Rimbaud.

Everyone gets to have their own Rimbaud—Rimbaud the gay, Rimbaud the druggie, Rimbaud the seer, Rimbaud the precocious, Rimbaud the wayfarer, Rimbaud the misunderstood, Rimbaud the figure. Eminently claimable. Endlessly categorizable. Infinitely untranslatable. Relentlessly translated.

It might be important to mention that my Rimbaud is inseperable from Rambo.

It all started because I made a pretentious joke in a grad school workshop that landed well, and then I kept trying to use it as a line in a poem. “No no, you said Rimbaud, I said Rambo,” I inserted again and again into the post-modern confessionals I was doing at the time (cringe). And it never worked. This is such a great line! I said to myself one day (though it isn’t), Why can’t I make it work?

Well, dummy, I answered myself, Maybe it’s because you’ve never read Rimbaud or seen Rambo.

So I remedied that, with myriad translations and phone-thick bios. I laid books open on top of one another:

[box]

As I was going down impassive Rivers,

I no longer felt myself guided by haulers (trans. Wallace Fowlie)

While swept downstream on indifferent Rivers,

I felt the boatmen’s tow-ropes slacken (trans. Wyatt Mason)

As I came down the impassible Rivers,

I felt no more the bargemen’s guiding hands (trans. Louise Varese)

I followed deadpan Rivers down and down,

And knew my haulers had let go the ropes (trans. Martin Sorrell)

I felt my guides no longer carried me—

as we sailed down the virgin Amazon (trans. Robert Lowell)

[/box]

I tried to find Rimbaud by stringing gods eyes between the synonyms. I was astonished by the gaps between what Rimbaud himself seemed like to me, and what Rimbaud’s disciples wax on about. I was entranced by the astronomical interstices of translation, and by the deafening power of legend.

And I watched the Rambo movies, read the screenplays and the original carnographic novel, read the novelizations of First Blood Part II and Rambo III (I have suffered for my art). First watching the first film was what tipped me over into this Rambo/Rimbaud poems obsession I think—I could not figure out how the first movie’s John Rambo, the put-upon Vietnam vet with PTSD who doesn’t kill a single person in the film (though he does, I admit, do an extraordinary amount of property damage) was the same macho bullet-spraying Russians-vanquishing Rambo that Reagan talked about, the shirtless machine-gunning poster child of everything that was dumb about the 80s.

And I was mesmerized by the difference between what the filmmakers intended by, for instance, the scene in Rambo III where he cauterizes his own wound by pouring gunpowder into it and setting it alight—something brave and dramatic—and how the audience actually responds—with snorting laughter.

[script_teaser]Everything’s a bad translation, I decided at one point—the difference between what’s in your heart/head and what gets on paper, the difference between the printed and the spoken, all the other things other people hear when you say “poet”, your Rimbaud, my Rambo.[/script_teaser]

During the years I wrote Rambo/Rimbaud poems, it didn’t occur to me that what I was doing was looking for a way in, a way to understand these figures that had no resonance for me, as the world seemed to say they should.

Plus, of course, putting Rambo and Rimbaud together is just inherently funny.

[articlequote]”If we are absolutely modern—and we are—it’s because Rimbaud commanded us to be,” says John Ashberry.

“Interpret his work as you like, explain his life as you will, still there is no living him down,” says Henry Miller.

“All those who study Rimbaud soon reach a gulf of mystery which their imagination and intuition seem unable to bridge,” says Enid Starkie.

“Poetry will no longer accompany action, but will lead it” says Rimbaud, my Rimbaud. [/articlequote]

[line]

[box]

Filling Station (Rambo & Rimbaud, Proprietors)

A thoroughly dirty

little gas station

on a high desert road,

oil-soaked, oil-permeated

to an overall

mirage translucency

under the bored stare

of an afternoon which asks, if,

since things are so slow,

could it go early?

Rimbaud sits in the shade

of the cement porch

behind the pumps

on a crushed and grease-

impregnated wickerwork taboret,

part of a set,

beside a big hirsute begonia.

He wears a bowler hat

and a dirty, oil-soaked monkey suit,

too large, and rolled at the legs

and the arms into fat cuffs.

He is struggling

to remove his boots.

The taboret creaks

underneath him

as if it needs more oil.

Rambo sits on the dirty

wicker sofa, sharpening

a large black knife.

It slides along the whetstone,

back along the whetstone,

along the whetstone,

back along the whetstone.

A comfy shushing.

His oil-soaked monkey suit

strains across his pectorals

and cuts into his jugular,

an indentation in danger

of becoming permanent.

He also wears a bowler hat.

His has a red band,

the only note

of certain color

in the station.

Even the daisy stitch

and marguerites on the big

dim doily draping the low back

of the wicker sofa

are heavy with oil.

Or were perhaps

crocheted out of it.

Rambo stands, unzips his monkey suit

halfway and ties the arms

together at the waist.

His scarred chest gleams

like it’s been oiled.

He does push-ups.

Rimbaud writes lists

on sheets of Your Co. Name

notepad paper,

the ballpoint slipping

across little rosettes of grease.

A hundred says Rambo.

A hundred and one.

The old neon sign spits

ESSO—SO—SO—SO

at its proprietors.

_______

The sun dawns like a tossed coin

landing heads after coming up

every time tails.

Rambo slowly settles his bowler hat

firmly, with both hands,

onto his head. The muscles

in his back and biceps quilt.

Rimbaud clumps

around back of the station, his boots,

lewd, sticking out their tongues.

There’s a bleached and shredded

tarpaulin lean-to

strung with spent light sticks

tied up with bits of shoelace.

Inside the lean-to everything

is mildew, mildew, mildew.

Parked catacorner

an ancient mini pickup truck,

its original color dubious.

_______

Rambo and Rimbaud

push the mini pickup

up to the top of a rise.

With Rambo in the driver’s seat

the little truck rolls backward

towards the station.

Rambo steers it

right at the pump island,

diving out of the cab

at the dire moment.

He hustles up the hill,

losing and retrieving

his bowler hat in the process.

Rimbaud upends a duffel

with three good shakes.

A bow drops. An arrow.

The greasy doily and a Zippo.

He flicks open the Zippo

and flips it shut,

flicks it open and flicks it shut,

a systolic clicking.

Rambo wraps the tip of the arrow

in the doily and Rimbaud,

with ceremony, lights it.

Rambo notches the arrow

and aims, the gasoline

from the knocked-over pumps

misting upright

and wisping sideways.

He lets the arrow,

with a snapping twang,

quite musical, fly.

Across the ground

a pulled thread, electric blue,

molts into flames,

low and peach-colored.

The sprays of gasoline

catch and thicken, rising twinned,

orange and blood orange,

spiraling askew

with infinite spongey flame.

And then at last—oh

but it is loud!

the rampant overlap of kablooeys.

Toasty heat

embraces the hill.

Rimbaud and Rambo

dance and cavort

though the smell is acrid

and makes their nostrils sting

and their eyes water.

The roiling plumage

of the filling station,

moil bearable to no one

but from afar, blown up,

and blowing up.

Will they open a new station?

They might stick out their thumbs

at the nearest crossroads.

Where would they go?

Somewhere

there is a place for them.

For somewhere

there is a place for us all.

[/box]

[line][line]

[box]

Sources for quotations & translations (in order)

Flores, Angel, ed. Smith, Patti, introduction. The Anchor Anthology of French Poetry. 3rd edition. Anchor Books, 2000.

Rimbaud, Arthur. Complete Works. Trans. Paul Schmidt. 5th edition. Harper Perennial, 1975.

Rimbaud, Arthur. Complete Works, Selected Letters. Trans. Wallace Fowlie. University of Chicago Press, 1966.

Rimbaud, Arthur. Arthur Rimbaud: Poetry and Prose. Trans. Wyatt Mason. Modern Library. 2002.

Rimbaud, Arthur. A Season in Hell and The Drunken Boat. Trans. Louise Varese. New Directions Publishing. 1945.

Rimbaud, Arthur. Collected Poems. Trans. Martin Sorrell. Oxford University Press. 2001.

Lowell, Robert. Imitations. 9th ed. The Noonday Press. 1958.

Rimbaud, Arthur. Illuminations. Trans. John Ashbery. W.W. Norton & Company. 2011.

Miller, Henry. The Time of the Assassins: A Study of Rimbaud. New Directions. 1946.

Starkie, Enid. Arthur Rimbaud. New Directions, 1961.

Rimbaud, Arthur. Illuminations. Trans. Louise Varese. 2nd ed. New Directions. 1957.

[/box]

[line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/CatherineBullPhoto-e1429197591257.jpg[/textwrap_image]Catherine Bull is a poet from the Pacific Northwest whose work can be found in FIELD, Literary Bohemian, and The Broken City. Other Rambo/Rimbaud poems can be read in The Bellingham Review (read more at link!) and Beatdom. She holds degrees in Poetry and English/Creative Writing from Oberlin College and U.C. Davis, and writes about contemporary poetry and poetics, plus film reviews, at catherinebull.com. Catherine came to us this year via my old friend Elizabeth Harlan-Ferlo, whose terrific piece on Linda Gregerson graced our Day 5 this year.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]