4th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 24 :: The Difference Between the Nautical & Geographical Mile :: Joe Pan on Denis Johnson

[line]I find it difficult to discuss Denis Johnson with any real authority, not because I don’t have anything to say regarding his consummate ability to describe the human traits that render fictional characters three-dimensional, but because Denis Johnson is the authority, in my mind, of saying anything at all. His sentences arrive hot in the ear, like an intimate aside. When he shares a bit of dark humor you find yourself snorting out of politeness, if not genuine enjoyment. It would be untrue to say I’m envious of his gifts; I’m absolutely livid with jealousy. His sporty lines squiggle into the space between the trance-inducing, economically pared-down style of Don DeLillo & the wandering, playful, but despairing vulnerability of Charlie D’Ambrosio, with sentences honed to a pinpoint accuracy. Add a splash of Blake’s Christian mysticism & the largesse of Whitman, to taste, & you’re well on your way to creating a cocktail by turns wondrous, violent, flabbergasting, & illuminating. If I could consume one human being & gain his superpowers I would fricassee Denis Johnson. As it stands, I can either use what I’ve learned from him or go back to imitating him. Literally. For some months after first reading Jesus’ Son fifteen years ago, I rewrote paragraphs from the book, whole pages even, in an effort to gain passage into the author’s mind & discover how it was he made the magic happen.

[line]I find it difficult to discuss Denis Johnson with any real authority, not because I don’t have anything to say regarding his consummate ability to describe the human traits that render fictional characters three-dimensional, but because Denis Johnson is the authority, in my mind, of saying anything at all. His sentences arrive hot in the ear, like an intimate aside. When he shares a bit of dark humor you find yourself snorting out of politeness, if not genuine enjoyment. It would be untrue to say I’m envious of his gifts; I’m absolutely livid with jealousy. His sporty lines squiggle into the space between the trance-inducing, economically pared-down style of Don DeLillo & the wandering, playful, but despairing vulnerability of Charlie D’Ambrosio, with sentences honed to a pinpoint accuracy. Add a splash of Blake’s Christian mysticism & the largesse of Whitman, to taste, & you’re well on your way to creating a cocktail by turns wondrous, violent, flabbergasting, & illuminating. If I could consume one human being & gain his superpowers I would fricassee Denis Johnson. As it stands, I can either use what I’ve learned from him or go back to imitating him. Literally. For some months after first reading Jesus’ Son fifteen years ago, I rewrote paragraphs from the book, whole pages even, in an effort to gain passage into the author’s mind & discover how it was he made the magic happen.

It was during these faltering attempts at transference that I began experiencing Denis Johnson’s sentences as tiny, pressurized universes. There’s a great deal of dark space in them, the space of things left unsaid, but the few lighted points ignite within the mind a much grander scene, complete with dying stars, aggressive rogue asteroids, sick planets, and their emotional satellites. To keep his prose spare & rushing forward, Johnson relies on implication to do a lot of the dirty work. I would love to quote in its entirety Francine Prose’s unpacking of the first paragraph of Johnson’s debut novel, Angels, which appeared as part of an essay in her book Reading Like a Writer, but rather than hand over the remote, here is an excerpt:

[articlequote]Two words, “Oakland Greyhound,” are enough to give us our bearings, both geographically and socioeconomically…Baby Ellen’s name, and the fact that the nuns are playing I-see-you with the kids, spares the writer from having to tell us that they are kids…[W]hen Jamie projects her doubts and fears about her self-presentation (pants, makeup) and her situation (she’s left her husband and may have few employment options aside from prostitution) onto the nuns, regarding and judging herself from their viewpoint, Johnson performs the difficult feat of enabling us to see his heroine simultaneously from the inside and the outside….Every detail…grounds the character so firmly in a recognizable reality, however peculiar and altered, that by the second paragraph we’re willing to accept the loopy poetry of a consciousness that registers the “mutilated” luggage and expands to embrace the idea that a paper sack could contain a lifetime of regrets, justifications, and wounds.*[/articlequote]

This leap from structured narrative realism (recognizable reality) to a kind of lyrically emotive dynamism (loopy poetry) is one that Johnson takes regularly, often during pivotal scenes, in moments of climax you might not recognize as climax until the sky is falling down around you. The shift from realism to dynamism can be disconcerting at first, but after several encounters, one begins to understand its reasoning & the importance of its role in the storytelling. By modulating the color & complexity of the language used in his descriptions, Johnson repeatedly places us squarely in the ever-changing psychological framework of whatever character we’re engaged with. In this way we receive a more complete, albeit fragile, rendering of the character’s complicated relationship with a broken world. Sometimes drugs are involved, which half-accounts for the musical or poetic nature of the descriptions, but these shifts—as much existentially philosophical as psychologically motivated—are just as likely to occur during moments of deep sobriety. These breaks in consciousness, willed or not, take place during some of the more interesting & evocative scenes, indicating a point where real & imagined worlds overlap. Take for example this scene from the story “Dundun” in Jesus’ Son—three men in a car, one of whom has been shot, are driving to a hospital:

[box]Dundun said, “What about the brakes? You get them working?”

“The emergency brake does. That’s enough.”

“What about the radio?” Dundun punched the button, and the radio came on making an emission like a meat grinder.

He turned it off and then on, and now it burbled like a machine that polishes stones all night.

“How about you?” I asked Mclnnes. “Are you comfortable?”

“What do you think?” Mclnnes said. It was a long straight road through dry fields as far as a person could see. You’d think the sky didn’t have any air in it, and the earth was made of paper. Rather than moving, we were just getting smaller and smaller.

What can be said about those fields? There were blackbirds circling above their own shadows, and beneath them the cows stood around smelling one another’s butts. Dundun spat his gum out the window while digging in his shirt pocket for his Winstons. He lit a Winston with a match. That was all there was to say. [/box]

Here Johnson exposes his tragic narrator’s clueless narcissism (for clarity, there’s a guy dying in the backseat while two addicts fidget with the radio) by utilizing blunt dialogue to imbue the scene with a realistic feel, only to undermine that realism with a warped interior soliloquy that betrays the speaker’s altered state using a flighty but beautiful series of visual shifts that border on revelation. Confronted with this, the reader takes a mental step back, rightly questioning the protagonist’s ability to differentiate fact from fiction. We as readers realize we’re dealing with a flawed consciousness here, rather than a trustworthy authority, which is to some degree our default perspective with regards to narrators. How can we possibly trust this speaker with anything again? But then, how can we not?—surely he can’t lie about everything! The fields, the car, the Winston. Earlier I opted to separate the real world from the imagined, but as we know, there is no real world in books, there’s only language. A delightful hiccup accompanies the uncomfortable moment one realizes one’s reading an untrustworthy narrator, because we want not only to interact with characters in books, it seems we want relate to them as well. Our brains happily fill in what details the author omits, & in our revising & reimagining a story or text set before us, we can’t help but calibrate characters according to our liking. But when we realize they’re lying, to us, their closest confidants, it’s like we’re suddenly lying to ourselves, & what a dirty little game the author’s played on us. We are left feeling a bit disabused, possibly, & maybe less apt to be as generous with our emotions next time. Following this uninvited hiccup, though, we usually continue with our reading, but with a measured distance, waiting for the next instance of insubordination, which in the end will result in the kind of terrible final reckoning liars & flawed characters in fiction are often dealt.

Denis Johnson writes beautiful lies & complicated liars, which is to say, it’s difficult to distinguish between the bad from the good, because everyone is a sinner & a saint, depending on when you find them.

From “Dundun”:

[articlequote] If I opened up your head and ran a hot soldering iron around in your brain, I might turn you into someone like that.” [/articlequote]

Johnson’s pen is an eloquent & effective soldering iron. He also excels at putting to work the inherent lyric musicality of language to develop consciousness in regards to reader & character progression. (To paraphrase William Gass, whenever a character learns something, his or her consciousness shifts, & when consciousness shifts, so must the language used to represent it.) This lends itself well to many challenges of writing: pace, rhythm, drive, everything that accounts for narrative progression. Including portent. You can call it foreshadowing, but you’d be undercutting the sense of overwhelming human dread & inevitability that propels you forward in your reading of a Johnson novel. He’s a master at constraining time, character development through concise description, & explicating the various ways we as humans emotionally self-sabotage. You can find the same attention to tension in the lithe but endearing Train Dreams or the sad, frank depths of the National Book Award-winning Tree of Smoke. But I’m thinking of poor goddamn Bill Houston here, whose fate in Angels, reported by way of interior monologue, & which I won’t spoil by describing, is for me one of the most powerful scenes in all of literature.

All of this begins with managing the musicality & flow of language. His fluid paragraphs pack more information per printed page or pixel than most, which is to say, he’s ruined a lot of books for me. That’s the problem with great writers. You walk into the Strand or Book Thug Nation or Unnameable Books & crack open an author who’s been getting a lot of press lately & settle down into those first few paragraphs & suddenly you’re drifting away from it, because stored somewhere in your lizard brain is a neural cluster responsible for reactions against not quite rancid but not quite palatable meat, & you are—without even realizing it—weighing the heaviness of the poetry or prose against its literary forebears. You are judging the narrative switchbacks or poetic line breaks, resisting asides, evaluating the musicality and your sense of the author’s determination, or some sense of authenticity, along with all the other things that great writing calls upon when effectively disappearing the page before your eyes.

It’s a bit unfair to judge in such a way—different books seek different things, & in these moments it’s best to remind oneself that writers stack their talents in accordance to their pursuits. But we do judge, because we like to return to those great chroniclers who offer us greater riches. Which is why I return to Johnson’s wry but heartbreakingly sincere renderings of human fallibility, construed with such perfect, clarifying, encapsulating phrases.

Regarding these phrases, it’s easy to think, “Well, here’s someone who can spin a good sentence.” But then I try visualizing for a moment the book’s lexicographical negative. I imagine seeing all the words that might have been used to create a scene from a Denis Johnson book—all the unnecessary actions that were erased made suddenly visible, like a character’s switching of hands, the uncomfortable shifting from foot to foot, the descriptions of place & space & time, the evaluative descriptions left unremarked upon, or erased, or revised, & in their place, a single sentence, an entire resonating moment cleft of unnecessary action & feelings, to be boiled down to its essential urgency.

It’s easy to imagine the word-litter crowding this invisible spectrum with any writer, but with Johnson, one senses a real possibility that this is what’s happening, that he’s visualizing a world as if it’s real & doing the necessary cutting, tweaking, judging, & meshing in order to bring us something that feels lived in, authentic. One senses a mind fully present in its habitat, & full, to an almost pitiable degree, of an earnest need to represent a moment dutifully, with sincerity, understanding, patience, & a touching degree of generosity.

Here is a poem I read drunkenly to friends at an impromptu get-together at my house a few weekends ago. Afterwards, I looked into their faces, hoping to find there something inconsolable. But they weren’t inconsolable, they were filled with joy at the novelty of having been read to by a poet who minutes before had been inundating them with hundreds of ridiculous gifs culled from the internet. The inconsolable part was in me, in my memory of the small moments I’d spent in the mind of the narrator of this poem I’m now sharing with you. It’s the titular piece from The Incognito Lounge, Johnson’s third book of poetry, & contains the kind of textured sadness it’s wonderful to hold inside you as you walk out onto the sunny streets of Brooklyn, feeling both present & left behind by the passing of time. The kind of erased feeling that leaves you spending an inordinate amount of time watching strangers drink coffee, or scold their small dogs. Maybe there’s another writer who does this for you. For me that writer is Denis Johnson.

[box]

The Incognito Lounge

The manager lady of this

apartment dwelling has a face

like a baseball with glasses and pathetically

repeats herself. The man next door

has a dog with a face that talks

of stupidity to the night, the swimming pool

has an empty, empty face.

My neighbor has his underwear on

tonight, standing among the parking spaces

advising his friend never to show

his face around here again.

I go everywhere with my eyes closed and two

eyeballs painted on my face. There is a woman

across the court with no face at all.

✶ ✶ ✶

They’re perfectly visible this evening,

about as unobtrusive as a storm of meteors,

these questions of happiness

plaguing the world.

My neighbor has sent his child to Utah

to be raised by the relatives of friends.

He’s out on the generous lawn

again, looking like he’s made

out of phosphorus.

✶ ✶ ✶

The manager lady has just returned

from the nearby graveyard, the last

ceremony for a crushed paramedic.

All day, news helicopters cruised aloft

going whatwhatwhatwhatwhat.

She pours me some boiled

coffee that tastes like noise,

warning me, once and for all,

to pack up my troubles in an old kit bag

and weep until the stones float away.

How will I ever be able to turn

from the window and feel love for her?—

to see her and stop seeing

this neighborhood, the towns of earth,

these tables at which the saints

sit down to the meal of temptations?

✶ ✶ ✶

And so on—nap, soup, window,

say a few words into the telephone,

smaller and smaller words.

Some TV or maybe, I don’t know, a brisk

rubber with cards nobody knows

how many there are of.

Couple of miserable gerbil

in a tiny, white cage, hysterical

friends rodomontading about goals

as if having them liquefied death.

Maybe invite the lady with no face

over here to explain all these elections:

life. Liberty. Pursuit.

✶ ✶ ✶

Maybe invite the lady with no face

over here to read my palm,

sit out on the porch here in Arizona

while she touches me.

Last night, some kind

of alarm went off up the street

that nobody responded to.

Small darling, it rang for you.

Everything suffers invisibly,

nothing is possible, in your face.

✶ ✶ ✶

The center of the world is closed.

The Beehive, the 8-Ball, the Yo-Yo,

the Granite and the Lightning and the Melody.

Only the Incognito Lounge is open.

My neighbor arrives.

They have the television on.

It’s a show about

my neighbor in a loneliness, a light,

walking the hour when every bed is a mouth.

Alleys of dark trash, exhaustion

shaped into residences—and what are the dogs

so sure of that they shout like citizens

driven from their minds in a stadium?

In his fist he holds a note

in his own handwriting,

the same message everyone carries

from place to place in the secret night,

the one that nobody asks you for

when you finally arrive, and the faces

turn to you playing the national anthem

and go blank, that’s

what the show is about, that message.

✶ ✶ ✶

I was raised up from tiny

childhood in those purple hills,

right slam on the brink of language,

and I claim it’s just as if

you can’t do anything to this moment,

that’s how inextinguishable

it all is. Sunset,

Arizona, everybody waiting

to get arrested, all very

much an honor, I assure you.

Maybe invite the lady with no face

to plead my cause, to get

me off the hook or name

me one good reason.

The air is full of megawatts

and the megawatts are full of silence.

She reaches to the radio like St. Theresa.

✶ ✶ ✶

Here at the center of the world

each wonderful store cherishes

in its mind undeflowerable

mannequins in a pale, electric light.

The parking lot is full,

everyone having the same dream

of shopping and shopping

through an afternoon

that changes like a face.

But these shoppers of America—

carrying their hearts toward the bluffs

of the counters like thoughtless purchases,

walking home under the sea,

standing in a dark house at midnight

before the open refrigerator, completely

transformed in the light…

✶ ✶ ✶

Every bus ride is like this one,

in the back the same two uniformed boy scouts

de-pantsing a little girl, up front

the woman whose mission is to tell the driver

over and over to shut up.

Maybe you permit yourself to find

it beautiful on this bus as it wafts

like a dirigible toward suburbia

over a continent of saloons,

over the robot desert that now turns

purple and comes slowly through the dust.

This is the moment you’ll seek

the words for over the imitation

and actual wood of successive

tabletops indefatigably,

when you watched a baby child

catch a bee against the tinted glass

and were married to a deep

comprehension and terror.

[/box]

—Denis Johnson, from The Incognito Lounge and Other Poems (Carnegie Mellon University Press, 1994). The Incognito Lounge was originally published by Random House and selected by Mark Strand for the National Poetry Series in 1982. The collection is now part of the Carnegie Mellon Classic Contemporary series.

I met Denis Johnson once, or several times, over the course of a day, beginning with a Q&A with students, of which I was one. He asked a quieted room if anyone knew the difference between a geographical mile & a nautical mile. Meters or feet, didn’t matter. We were stumped. We were exposed as writers without a curiosity for basic facts. He never told us the answer, moving on to another question for us. Later he would openly weep twice while recounting a story—once before twenty people, & again before two hundred or so—that involved a dead friend. If he were writing about himself, he wouldn’t go into voracious detail as to what psychological pressures instigated the break before a crowd of vaguely embarrassed & sympathetic listeners. The image of this large man hunched over the podium, hand to his face, would have been enough. It took all of about five seconds for Johnson to apologize & latch onto another point of discussion, having us travel away from that moment with him & join the cascade of another tale. Later, at a party in his honor, the graduate students of the writing program allowed him to sit alone in a chair staring straight forward, cowboy boots pointing ahead, as we cautiously circled about, ignoring him while conversing with each other, hijacking our nerves with a prescription of bottomless margaritas. After a while he simply got up & left.

God, there’s like a million ways to fail, isn’t there. The world is full of stances we quietly assume, for one reason or another, peripheries we peek over. Another thing that Denis Johnson is big on is redemption. It’s out there, in precious quantity. But you have to be willing to stare at yourself a good long while without blinking. & you have to be willing to receive it.

I wanted to ask if you consciously changed the music in your descriptions of objects & places to better serve the changing thoughts & behaviors of your characters. I guess it doesn’t matter now, so long as I believed that you did back then, & took that belief into my own work. I took your unanswered question, your desire to leave it unsaid, as a challenge. The geographical mile is 1855.3 meters. The nautical mile is slightly, almost negligibly less. They reference the same thing, a calculation of one minute of arc along the Earth’s equator. But to realize that there exists a variance in what is essentially the same truth, dependent entirely on perspective & available tools, has made, in how I now approach writing, all the difference.

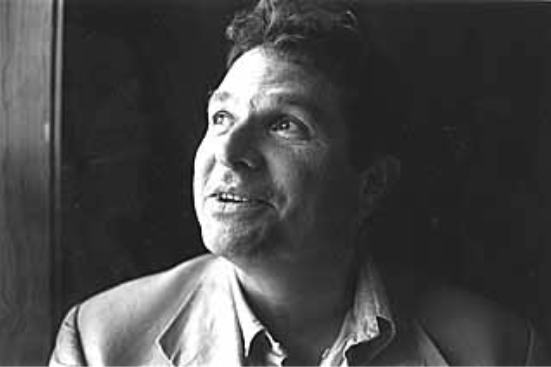

[line][line][textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Joe-Pan-photo-by-Adam-Courtney-e1429805472429.jpg[/textwrap_image]JOE PAN is the author of two poetry collections, Autobiomythography & Gallery (BAP) and Hiccups, or Autobiomythography II (Augury Books). He is the publisher and managing editor of Brooklyn Arts Press, serves as the poetry editor for the arts magazine Hyperallergic, and is the founder of the services-oriented activist group Brooklyn Artists Helping. His piece “Ode to the MQ-9 Reaper,” a hybrid work about drones, was excerpted and praised in The New York Times. In 2015 Joe will participate in Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s Process Space artist residency program on Governors Island. Joe attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, grew up along the Space Coast of Florida, and now lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

[line] [h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5] [mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”] [line] [recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]