5th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 16 :: Mark Gurarie on the Sly Science of Francis Ponge

[box]It’s hard to believe that this is our FIFTH annual 30/30/30 series, and that when this month is over we will have seeded and scattered ONE HUNDRED and FIFTY of these love-letters, these stories of gratitude and memory, into the world. Nearly 30 books, 3 magazines, countless events and online entries later, and this annual celebration shines like a beacon at the top of the heap of my very favorite things to have brought into being. [If you’re interested in going back through the earlier 120 entries, you can find them (in reverse chronological order) here.]

When I began this exercise on my own blog, in 2011, I began by speaking to National Poetry Month’s beginnings, in 1966, and wrote that my intentions “for my part, as a humble servant and practitioner of this lovely, loving art,” were to post a poem and/or brief history of a different poet…. as well as write and post a new poem a day. I do function well under stricture, but I soon realized this was an overwhelming errand.

Nonetheless the idea stuck — to have this month serve not only as one in which we flex our practical muscles but also one in which we reflect on inspiration, community, and tradition — and with The Operating System (then Exit Strata) available as a public platform to me, I invited others (and invited others to invite others) to join in the exercise. It is a series which perfectly models my intention to have the OS serve as an engine of open source education, of peer to peer value and knowledge circulation.

Sitting down at my computer so many years ago I would have never imagined that in the following five years I would be able to curate and gather 150 essays from so many gifted poets — ranging from students to award winning stars of the craft, from the US and abroad — to join in this effort. But I’m so so glad that this has come to be.

Enjoy! And share widely.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/box]

[line][line]

MARK GURARIE on The SLY SCIENCE of FRANCIS PONGE

[line][script_teaser]”Idéologiquement c’est la même chose: elle m’échappe, échappe à toute definition, mais laisse dans mon esprit et sur ce papier des traces, des taches informes.[/script_teaser]

[script_teaser]Ideologically this comes to the same thing: it escapes me, escapes all definition, but leaves traces, shapeless marks, in my mind and on this piece of paper.“ [/script_teaser]

[script_teaser]–Francis Ponge, De l’eau (Of Water) [/script_teaser]

[line]

Francis Ponge’s poetry is an investigation, there’s a kind of serene science to it. It’s a poetry that observes, that takes notes but also savors its own soup. Perhaps this is why Ponge’s poems, written as they were in the early to middle of the last century in France, seem so timeless, so relevant now. It’s a poetry that is able to marvel, wonder at the everyday, while also, cleverly but never too cute-ly commenting on the art of writing. I like to think of it as films in Ponge-O-scope: how joyful the poems are! How playful! And this from someone who saw two world wars, who fought in the French resistance, who saw so much destroyed by violence, by actual bombs.

Each prose poem (it seems a majority of his adopted that form) is a playful, purposeful description; he is the narrator to this documentary of the everyday, of received forms, nature, cigarettes, gymnasts, water, what have you. But, of course, Ponge isn’t afraid to wink: “A shell is a small thing, but I can exaggerate its size by putting it back where I found it on the expanse of sand,” he writes in Notes Toward a Shellfish. How lovely to consider the page a kind of beach, the word object nestled in the dunes, growing larger as it returns to the ground, surrounded by sand.

Here the eyes, the ears, the tongue are trained on the world around us, and that is what envelopes the reader because, as involved as it all is with observation, it also becomes its own linguistic territory. “It isn’t easy to define a pebble,” begins the poem, The Pebble, after which we get, among other things, a geologic consideration of the origins of the stone and a discourse that leads to the sun itself, the formation of the solar system, the expanse of geologic time, what that might mean to a pebble, and “the slow catastrophe of cooling, its history has been nothing but a perpetual disintegration.” The voice urges us to slow down—“The reader should not skim through this part too rapidly. He should stop to admire, not my thick elegiac expressions, but the grandeur and glory of a truth that could make them transluscent without seeming entirely overshadowed by them”—but the narrator will not. We are rewarded with glorious pages: a discourse on pebbles, on the earth, on commerce, the gentle language of the rocks, of physics, description, description, description of “the forms that stone, now scattered and humiliated throughout the world, assumes.” It’s incredible, the universe captured inside the mundane, neglected object, and the extent to which its materiality itself is more than a fitting subject.

It is probably true to say that every poet, every writer, is wearing a suit made of mirrors; she is a reflection of what she is reading, what she is hearing, what she is seeing. It is probably also true that there are lineages in poetry: that one can, if one likes, draw threads between writers, between approaches to form, between aesthetics as they continue to develop over both short and long periods of time. Certainly, in the MFA era and the era of the internet, it might be easy to plot and to track what is often called influence, and this ordering itself satisfies the human categorical imperative. It’s even in that sense Pongean (if that’s an adjective) to do so. Armchair philosophy aside, though, what gets fascinating are the ways in which these influences can be a kind of two way street, or perhaps something even messier. By this I mean not only the ways that a poet might be influenced by what she is reading, but also by the ways what she is working on might influence her reading.

Case in point of the above: A couple years ago, I was handed Francis Ponge’s Selected Poems by poet Matthew Yeager after one of the ad-hoc workshops that he would occasionally host. Why did Matt hand me this paperback volume (which I still need to return!)? Essentially, it’s because I had started writing poems in the manner of Ponge without even knowing it, and I obviously felt good enough about them to share with the group. What I said about it that night was that I was inspired by televised documentaries, things like Attenborough’s Blue Planet or Degrasse-Tyson’s Cosmos. It wasn’t the documentary approach or subject matter that caught me as much as the role of the narrator in them; I just love the way the words themselves set the scene, and got to wonder about the ways they might work without the adjoining footage. To that end, I might’ve gone on to my peers after taking another sip of wine, I began writing a series of prose poems that applied this approach to the mundane world of the corporate office building. The poems have simple, noun titles: The Drinking Fountain, The Stairs, The Ceiling Fans, The Corridors, etc., and they are a manner of still life or drawing from life.

It was therefore a revelation, later that same evening, to open the borrowed book to a poem called The Orange, and read:

[line][articlequote]But it’s not enough to recall the orange’s peculiar way of perfuming the air and delighting its torturer. We must call attention to the glorious color of the resulting liquid, and to how, as is not the case with lemon juice, the larynx has to open wide to pronounce its name as well as to ingest it.”[/articlequote][line]

I love how the object itself grounds everything, and yet there is at once the violence of eating the fruit, and that of saying its name.

To put it a touch dramatically, a kind of dance ensues: I read Ponge and think about my series—dip—and Ponge slyly hot steps into my sterile, corporate but also quite magical office—and spin.

But of course Ponge’s poems are more than life drawings or still-lifes; what he’s able to do—and come to think of it what my series probably fails at—is to also call attention to the artifice of it all, the extent to which that orange is a collection of (French) scratches on the page, a certain idea or association surrounding orange, and perhaps most importantly, a linguistic construct. Through it all, we get the kinds of nuggets about art and writing itself that I might someday apply were I ever lucky enough to actually teach poetry craft. Just look, I imagine myself saying to a class: in the poem Earth he describes a fistful of dirt in this way: “Past, not as memory or idea, but as matter.” What the hell else should a poem be?

The tragedy of it all, in some sense, is that I do not speak or read French. The translations I encounter in Selected Poems, done alternately by Margaret Guiton, John Montague and C.K. Williams, are wonderful, luminous, absolutely fantastic, but I also know that there are some surface level elements or word plays that I am missing. Once, while reading the book, I thought about how Ponge, himself, is a translator of what he is looking at and what he is thinking, and how to read Ponge in translation, on some level, might be even more in fitting with the spirit of his work. It’s bullshit, I know, but I’ll take it in absence of French lessons.

I identify with Ponge, too, because he is, a relatively obscure figure and gained little recognition in his life time; however, his admirers are, well, admirable themselves. He has hardly any notoriety at all until the publication of the collection Le parti pris des choses in 1942, when he is himself in his 40s. A sort of late bloomer myself, and likely to remain a relative unknown, I like the idea of this poet holding onto his vision, steadily plucking away over the course of decades as styles come and go, only to grow in reputation in later life and posthumously. I have very little idea about how it all went down for him, to be sure, but there must have been a steely resolve in it all (the man lived through world wars). I hope, as I continue to move forward, that I have something like that in me, rejections, submissions, jealousy and all that be damned. Ponge is not a rock star; he is an ancillary figure who in his lifetime gains the esteem of Camus, of Sartre, of Calvino. If I may, Ponge strikes me as a case like that of The Velvet Underground (at least in the 70s); few people bought the records, but everyone that did formed a band. It strikes me also that good poetry should do exactly this for the art form.

Anyway, there is much more that can be said about Ponge and his hyper-real and playful science. So many more yarns to spin, webs to weave about the way that he’s able to infuse personality and life into the inanimate or lend extra grace, wonder to the animate in the world around him, while guiding us through his pages. Instead, though, I leave you with a little section from Fauna and Flora, in which he is describing plants, but of course us too:

[line]

[line][articlequote]In Spring when, tired of restraining themselves, no longer able to hold

back, they emit a flood, a vomit of green, they think they’re breaking into

a polyphonic caniticle, bursting out of themselves, reaching out to,

embracing all of nature; in fact they’re merely producing thousands of

copies of the same note, the same word, the same leaf. [/articlequote][line]

It is fitting to consider poets as plant cells, vomiting up ourselves, saying the same things every spring.

[line][line]

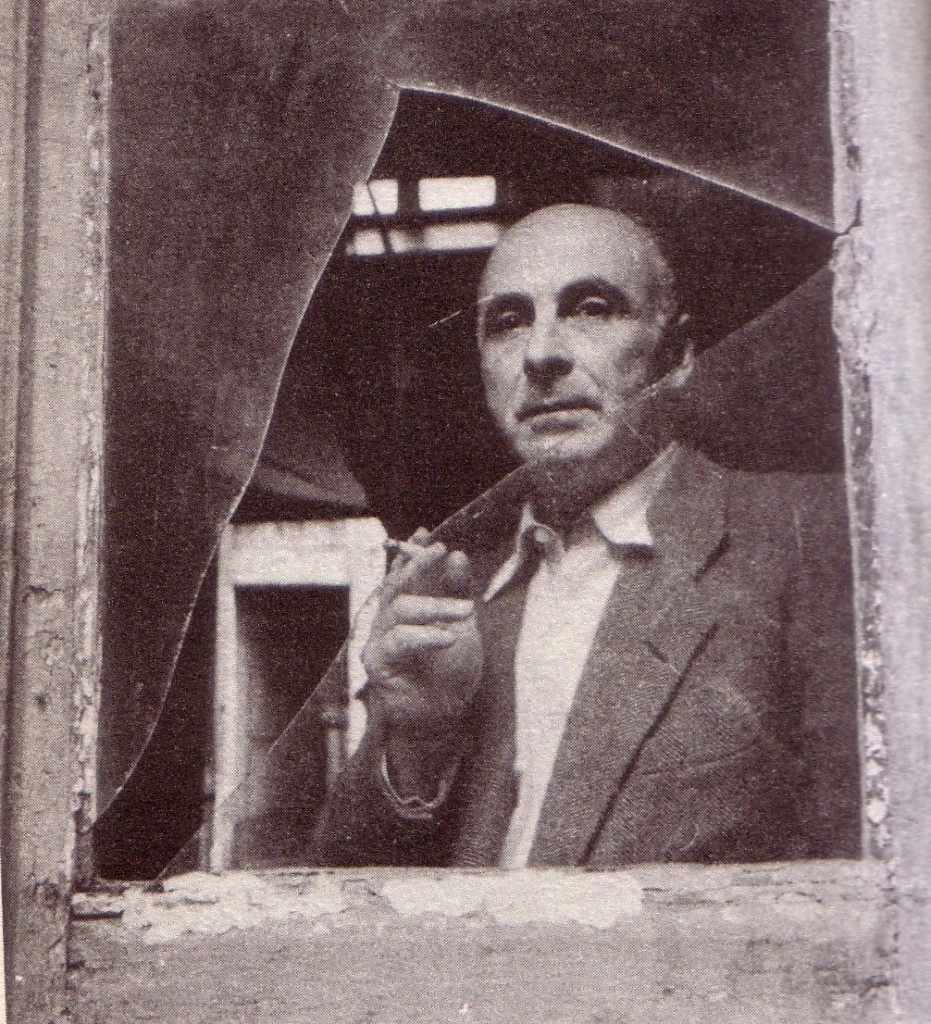

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Mark-at-Mic-2-e1460820825722.jpg[/textwrap_image] Originally of Cleveland, Ohio, Mark Gurarie currently splits time between Brooklyn, New York and Northampton, Massachusetts. He is a graduate of the New School’s MFA program, and his poems and prose have appeared in Pelt, Paper Darts, Sink Review, Everyday Genius, The Rumpus, The Literary Review, Coldfront, Publishers Weekly, Lyre Lyre and elsewhere. In 2012, the New School published Pop :: Song, the 2011 winner of its Poetry Chapbook Competition, and Mark’s debut full length poetry collection, Everybody’s Automat, was published by The Operating System in 2016. He co-curates the Mental Marginalia Poetry Reading Series in Brooklyn, serves as the Printed Matter Editor at Boog City and lends bass guitar and occasional vocals to psych-punk band, Galapagos Now!. In addition, he is an adjunct instructor teaching online for George Washington University, a book reviewer and a free-lance copywriter.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]