5th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 25 :: Ariel Resnikoff on the Hidden Eminences of Harold Schimmel

[box]It’s hard to believe that this is our FIFTH annual 30/30/30 series, and that when this month is over we will have seeded and scattered ONE HUNDRED and FIFTY of these love-letters, these stories of gratitude and memory, into the world. Nearly 30 books, 3 magazines, countless events and online entries later, and this annual celebration shines like a beacon at the top of the heap of my very favorite things to have brought into being. [If you’re interested in going back through the earlier 120 entries, you can find them (in reverse chronological order) here.]

When I began this exercise on my own blog, in 2011, I began by speaking to National Poetry Month’s beginnings, in 1966, and wrote that my intentions “for my part, as a humble servant and practitioner of this lovely, loving art,” were to post a poem and/or brief history of a different poet…. as well as write and post a new poem a day. I do function well under stricture, but I soon realized this was an overwhelming errand.

Nonetheless the idea stuck — to have this month serve not only as one in which we flex our practical muscles but also one in which we reflect on inspiration, community, and tradition — and with The Operating System (then Exit Strata) available as a public platform to me, I invited others (and invited others to invite others) to join in the exercise. It is a series which perfectly models my intention to have the OS serve as an engine of open source education, of peer to peer value and knowledge circulation.

Sitting down at my computer so many years ago I would have never imagined that in the following five years I would be able to curate and gather 150 essays from so many gifted poets — ranging from students to award winning stars of the craft, from the US and abroad — to join in this effort. But I’m so so glad that this has come to be.

Enjoy! And share widely.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/box]

[line][line]

New York School-Hebrew : Ariel Resnikoff on the Hidden Eminences of Harold Schimmel

I’m in uniform fresh from basic training Frank

all leanness of thighs moves to a bass-beat with a glass

of Jim Beam (his partner) on ice Edwin presents me

(this anonymous soldier) and we speak of a mutual philosopher-

friend’s fairness and decency “And when he wants his boy”

O’Hara attacks . . . “Wham.” I come-to-after through splintery

seconds of catching deer

like river minnows nipping at my toes Jane Freilicher

descending her ladder smiles wily sexy and Frank

devotes himself to pulling at his absent dinner-tie

You in all of this are where? In the corner

in the Whistler’s rocker — holding court with both

your hands heterosexual and learned . . . “ten dollars”

“car keys” and “thigh” in your poems were arranged with

Chardin-like precision or the floral exhibitions (set to the

botanic-calendar) at the Isabella Gardner Museum

—“I’m in Uniform” (1985, Hebrew; trans. Peter Cole)

[/box][line]

I

[line]

I first encountered Harold Schimmel in the pages of Paideuma, in a special issue dedicated to the life and work of Louis Zukofsky. Schimmel’s essay in that issue, “Zuk. Yehoash David Rex” —later collected in Caroll F. Terrell’s Louis Zukofsky: Man and Poet—addresses in detail the Yiddish modernist tenor of LZ’s early verse: “the music is Yiddish,” he writes, “not yet contrapuntal, not yet Bach: Jewish Folk Song despite the typically New York School-Yiddish modernism, ‘Plash. Night. Plash. Sky.’ (referring to Zukofsky’s “Ferry”).

[textwrap_image align=”right”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/2-e1461593433154.jpg[/textwrap_image] When I searched for Schimmel on the web, the most I could find was his ITHL (Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature) bio, which simply said he was an American-born poet and translator living in Jerusalem. The other thing that came up was a Jacket interview between Kent Johnson and David Shapiro, in which David casually remarks that Schimmel is “one of the ten best artists of the Hebrew language,” and that he should win a Nobel and “share it with a great Palestinian” (Jacket 37). But what was Schimmel’s connection to Zukofsky, I wanted to know—and had he known my cousin, Charles?—or to Yehoash and the Yiddish American modernists, for that matter? And why was he included in this special issue of Paideuma, alongside so many eminences from the New American Poetry and after.

The following year I was living in Tel Aviv, writing and translating through the Dorot Fellowship. I had gotten in touch with an old friend of my parents, Zali Gurevitch (a poet and anthropologist—the sole translator of Ashbery, Olson and Rothenberg into Hebrew), and he and I would often meet for coffee at a little café near his apartment, on Yehuda HaLevi St. During one of these meetings, the topic of Zukofsky’s yiddishkayt came up and Zali mentioned Schimmel’s name. I was floored. Schimmel was, according to Zali, both an eminent American writer, and also a leading figure in the contemporary Hebrew avant-garde, as well as an important mentor and friend to many of the radical Hebrew writers and artists of Zali’s generation.

A week later, we met. It was at the old Templar home of the Jerusalem poet, Gabriel Levin. Gabi had prepared some light food and drink and he, Zali, Schimmel and I, spent the afternoon “playing catch and release” (Reina Maria Rodriguez) across Hebrew and English, noshing and drinking, and smoking good grass, provided by Z.

After that, Schimmel and would I meet often, usually in south-Jerusalem (Arnona) on Yarden street, in the Schimmel’s third-story walk-up, an atelier-style wall–to-wall in paintings and sketches and photos and books. We talk of friends and family, alive and deceased, eat homemade olives carefully, and watch Palestine sunbirds hop about on the terrace; Dylan plays loud on the Hebrew stereo and the Yiddish American modernists read us “under the music” (Schimmel), drink our arak, smoke our grass.

I’ve become close to Varda Schimmel, as well: a wonderful photographer for years, she loves to guide me through the hundreds of photographs of loved-ones—many of them prominent writers and artists themselves—which she has taken over the last half-century. The three of us—and then four of us, after Rivka joins-up—spend the better part of the afternoon in the Schimmel’s apartment reading and watching the sunbirds and recounting the lives of our Levant ancestors, in France and the Americas, and drinking arak and eating Riga Gold sprats. (Or lemons with mustard—Varda’s favorite.)

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/4-e1461593586377.jpg[/textwrap_image] As the conversation flows, the Schimmel’s reveal bits and pieces of their pasts: the relationships and collaborations that have informed their literary/aesthetic lives. Those stories of friends—the names that come up in that apartment, among the books and the paintings and the arak and the fish and the lemons and the mustard and the grass—those names (just call them breathing nouns, says Bill B). My friends are never gone, says Schimmel, they’ve all left things behind, writings and stories and pictures and names.

Schimmel’s career spans more than sixty years, and traverses between/across English and Hebrew (and back again) countless times. It transfigures, between its languages, a number of disparate geographies—from the Americas to Europe and the Levant—and builds from Hebrew and English (and Greek and Arabic and Italian…) dense language-cartographies: poems as translingual maps. And Schimmel is the great poet-draftsman, radical linguist, “bird-like arranger” (Peter Cole, From Island to Island 14).

Aside from his many Hebrew books, including his ongoing serial “poem of a life,” Ar’a, (Aramaic: “Land”), Schimmel has been a prolific translator of Hebrew poetry and an important, though wholly peripheral, nomadic (in Pierre Joris’s sense) or outsider (in Jerry Rothenberg’s) participant in the New American poetry/poetics, as a writer of many English essays, meditations, poems and translations, and a longtime contributor, first to Epoch, and then to Sagetrieb, Paideuma and Conjunctions— if not merely through his numerous friendships and collaborations in the New American Poetry scenes and beyond.

What I’d like to do in the space remaining is to provide a brief history and selected bibliography of Schimmel’s work, including snap-shots of the (mostly early) poetry itself at various intervals. I do this most of all because when I began to write this essay, I could not find one in-depth online resource on Schimmel’s life or work. A PennSound and EPC page are forthcoming, as is Rivka Weinstock’s and my translation of Schimmels Shirei Malon Tsion (Songs from Hotel Zion). Many thanks are due to Peter Cole, Gabriel Levin, Adriana Jacobs and Shahar Bram, for their English translations of and writings on Schimmel, which were all a great help to my own writing here. [line]

II

[line]

[articlequote]

You fall in love with a new language and follow it. It grabs you. At the same time, that which is yours—your language—sort of breaks apart. You can’t take a step forward without this opposing disintegration.”

—Schimmel (interview with Helit Yeshurun; trans. Adriana Jacobs)

[/articlequote][line]

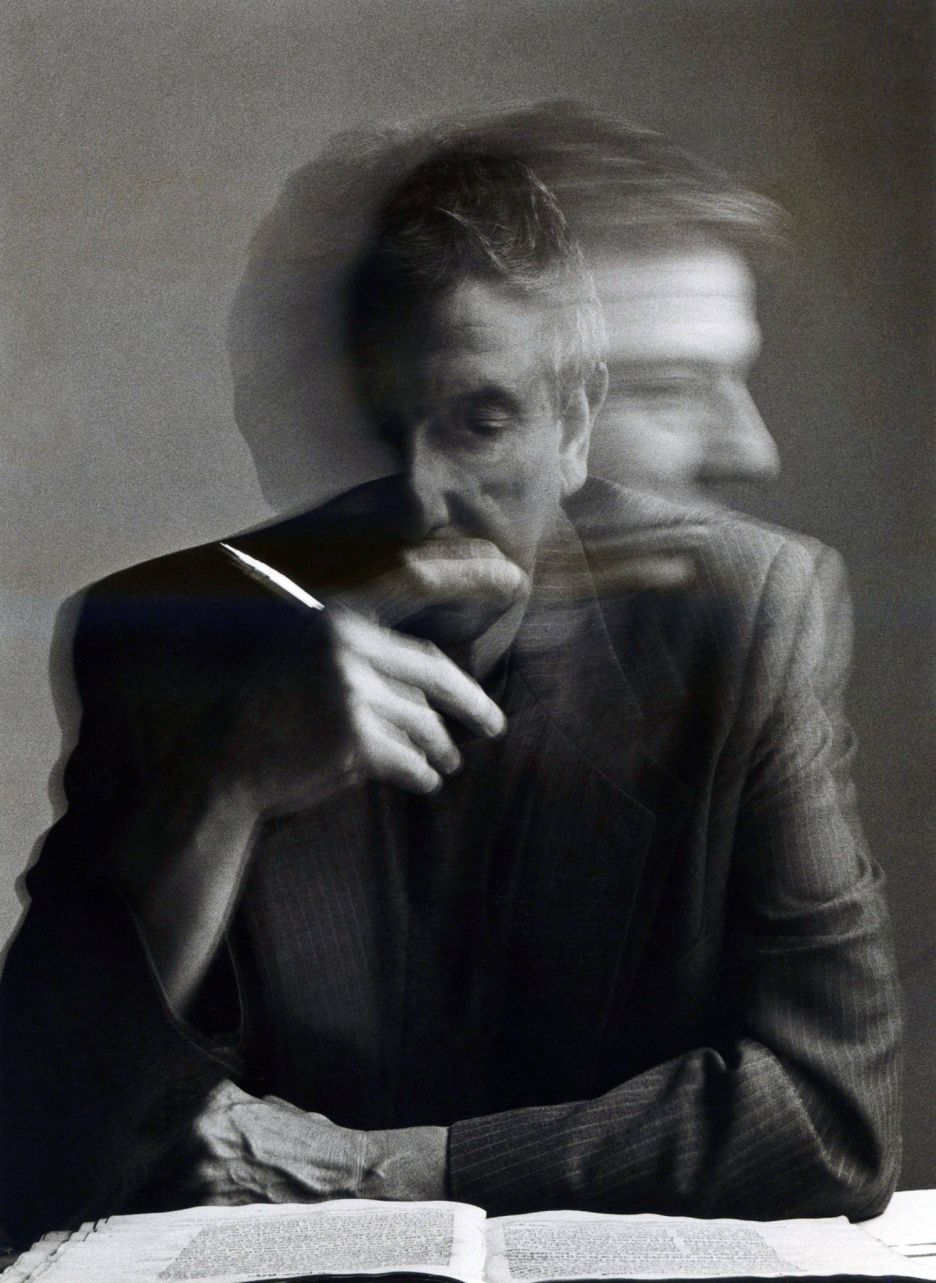

[textwrap_image align=”right”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/5-e1461593923150.jpg[/textwrap_image]Harold Schimmel was born in 1935 in Bayonne, New Jersey. He grew up in a religious Jewish family, and though his first language was English, he was surrounded early on by Hebrew and Yiddish . As a boy he studied at a yeshive ketone (religious primary school) in Boro Park, Brooklyn.

In the mid-1950s, Schimmel attended Cornell University and participated in a flourishing undergraduate literary/arts scene there, which included, Steve Katz, Thomas Pynchon, Susan Brownmiller, Ron Sukenick, Richard Fariña and Steve Reich, among others. Vladamir Nabokov was on faculty in those days and, according to Katz, “went out of his way to contact [Schimmel] after reading a couple of his poems in the student literary magazine,” Epoch (Time’s Wallet 36).

[line]

[box]

Like I was telling Katz in the

bicycle shop—

the thing’s to learn to work in an un-

settled state . . . ”But the Elegies”

he says, “Rilke spent a lifetime looking

for the place.”

The Schloss Duino faces the Tito-side

Of Trieste.

—from “Words for Elio” (1962, English)

[/box][line]

After graduating from Cornell, Schimmel moved to Waltham, MA to pursue a Masters degree in English at Brandeis University. He worked closely there with the critic-editor and co-founder of the Partisan Review, Phillip Rahv. On weekends he took the train down to New York to visit his friend and mentor, Edwin Denby. It was Denby who first brought Schimmel into the New York School scene of the late-1950s, introducing him to Frank O’Hara, among others, and inviting him to various parties and openings around the City.

[box]

Shatzkin reading to me in Yiddish

from the new testament

(blessed be the God who got me this far)

Not study,

but sitting under the silvered fig; on the edges

like the Shem-tov,

where even the toe-nail parings

are carried away in system by the ants.

Martin Buber meeting the horse’s eye

in the stalla.

Up on the roof, under the bed-clothes,

God coming down the chimney,

Recognizing the mouth under the beard.

A stubbed-toe for every blasphemy!

“With broken talk and foreignisms

I must speak to this people.”

—from “My Life” (1962, English)

[/box]

[line]

In 1958, Schimmel entered the US Army. He was stationed in Verona, Italy for two years, in the same unit as the New York artist, George Schneeman and the former US poet-Laureate, Charles Wright. The three men became close friends and were important early influences on one another. Wright, in fact, attributes his earliest foray into poetry to his friendship with Schimmel: “It was when I was in the army serving in Italy,” he says, in a recent Library of Congress interview

[articlequote]…A friend of mine who was already writing poetry, named Harold Schimmel, had given me selected poems of Pound and said, “When you go out there read this poem out on the peninsula.” And I did and I was totally taken with it, you know?…but that’s when I started when I was 23 years old (“On Being the Poet Laureate”) [/articlequote]

And likewise, as Bill Berkson recently recalled to me, it was Schimmel who convinced Schneeman to become a visual artist instead of a poet. He was also the link between Schneeman and Steve Katz, the two of whom became lifelong friends and collaborators.

[line][box]

George! Quick bring the canvas.

I am feeling like Toshio Neruda here in the sun,

an undershirt turned around the head

like swallows nesting, their purple

membranes trembling in an evergreen.

Below them in their blindness,

THE EYE OF THE ALMOND! A bank of sunlight

Drops plumb for the heart, but it won’t take

The complement, the old road

Mounting the river-bed to its plain—

(a stillness farther than hers)

—“Laughter’s a long way off” (1962, English)

[/box][line]

Schimmel’s first (and to date only) full collection of English poetry, First Poems, came out in 1962 in Lecce, Italy (Edizioni Milella), and included a landscape drawing by Schneeman on the cover page. Later that year he emigrated to Israel. “That was a loss to the American language,” writes Katz. “He was the first to ever show me poems by Frank O’Hara” (Time’s Wallet 37)

[line][box]

The sun is here.

All my handkerchiefs have my name

now in Hebrew.

I can’t even blow my nose

without feeling jewish. I am even

complimented by some fellow

clingers-to-zion with statements

like : “it sits well on you,

Harold” ie my jewishness.

Or the other day. “You know,

Herbert really likes you.

He says you’re a real

jew”

—from “Two Views of Jerusalem” (1964, English)

[/box][line]

In 1965, the editors at Epoch described Schimmel in the following way:

[articlequote]

Harold Schimmel is, according to our frequent re-assertions, one of the most powerful voices in contemporary poetry in English; his continued residence in Jerusalem removes him from the American scene. [/articlequote]

Schimmel, however, was hard at work bringing the “American scene” to Jerusalem. In 1968 he edited Get That: New York School Special (Jerusalem, Motsa), which included English writing from Steve Katz, Ted Berrigan, Ron Padgett, James Schuyler, Joanna Russ, Michael Brownstein, Peter Schjeldahl, and Schimmel himself. That same year, he published his first book of Hebrew poems, HaShirim (The Poems):

[line][box]

Gerard Malanga eats an apple under a gorgeous hat

in a film by Andy Warhol

“the primitive” from the Street of Prophets draws peasants healthier

than from a more-ancient era return in darkenss, with pushkes (now-empty)

from JNF

“Manhattan or Martini?” in a blurry photo . . .

—from “The Triangle” (1968, Hebrew; trans. is mine)

[/box][line]

The bunch of poets and artists that Schimmel became involved with in Israel, what I often refer to as the “Jerusalem School,” included, Yehuda Amichai, Dennis Silk, Sasha Petrova, Aryeh Sachs, Aharon Shabtai and the Hebrew American painter, Ivan Schwebel; and later: Zali Gurevitch, Yorik Verete, Gabi Levin, Peter Cole, Seth Altholz, Linda Zisquit and Jenny Feldman, among others. At the same time, Schimmel kept up correspondence with many of his closest friends in the United States, writing for years to Schneeman, Katz, Denby and Wright, but also to Guy Davenport, Hugh Kenner, and David Shapiro, among others. He and Varda hosted George and Marry Oppen, Bob and Penelope Creeley, Saul Bellow, Avrom Sutskever, and even Robert Lowell (after whom Schimmel titled his 1985 book of New York School-Hebrew sonnets) in their Jerusalem home. Schimmel also continued to publish English essays, poems and translations in American poetry/poetics magazines and journals—even as he lead a parallel Hebrew writing life—for many years.

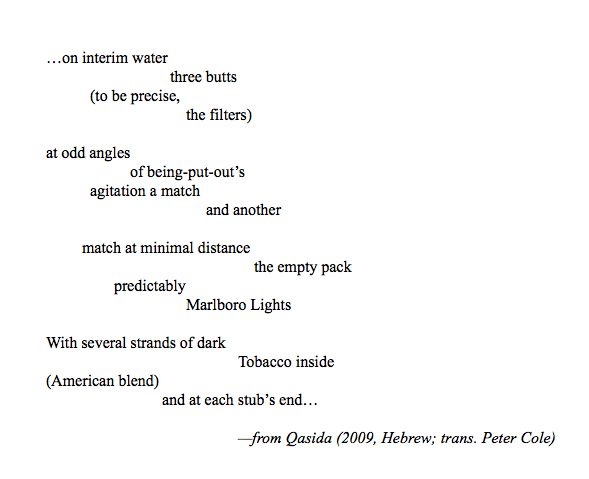

Even Schimmel’s great Qasida (2009)—a (post)modern Hebrew take on the pre-Islamic Arabic Ode—relies, in part, on a New York School-Hebrew sensibility. Afterall, in his 1978 Paideuma essay on Zukofsky, Schimmel pays close attention to Zuk’s use of the New York School-Yiddish poet, Yehoash, and his fartaytshn-un-farbesern (Yiddish: free translation, lit. translated-and-made-better) of Bedouin verse into Yiddish. “Not transference from language to language,” writes Schimmel, “but regeneration as the materials move…”[line]

[line]What David Roskies has said about the radical Yiddish modernist, Mikhl Likht, is valid also for Schimmel: that he is thinking in one language as he writes in another. Or as Schimmel himself writes of Avoth Yeshurun: “the lingua franca of the poet is the product of a multiple vision.” Schimmel’s vision relies on an aesthetics of the local and nomadic, translational and untranslatable, singular and polyvocal. His writing enacts a “double-life” or “double eternity” as Yeshurun called it; or as Schimmel writes (in a long Hebrew poem dedicated to LZ):

[box]

You do not see me

In fact I’m not here . . .

The task bending my neck

We’ll meet sometime

—from “1880” (Hebrew, 1981; trans. Guy Davenport with Schimmel).

[/box]

[line][line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/6-e1461593730163.jpeg[/textwrap_image] Ariel Resnikoff (reading, at right, in this shot) is a poet, translator and editor. His most recent works include the chapbook Between Shades (Materialist Press, 2014) and the collaborative pamphlet Ten Four: Poems, Translations, Variations (The Operating System, 2015) with Jerome Rothenberg. His poetry, essays and translations have appeared or are forthcoming in a number of journals and magazines, including The Wolf Magazine for Poetry, Eleven Eleven, White Wall Review, Jacket2 and Mantis, among others. With Stephen Ross, he is at work on the first full-length translation and critical edition of Mikhl Likht’s Yiddish modernist long poem,Protsesiyes (Processions). Ariel is an editor-at-large of Global Modernists on Modernism: A Sourcebook(forthcoming Bloomsbury, 2017) and curates the “Multilingual Poetics” reading/talk series at Kelly Writers House. He has studied multilingual diaspora writing at the University of California in Santa Cruz, McGill University, the University of Oxford, and independently in more than twenty countries over the past ten years. He is currently reading for a PhD in comparative literature at the University of Pennsylvania and lives with his wife, Rivka Weinstock, in the Cedar Park neighborhood of West Philadelphia.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]