5th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 6 :: Don Zirilli on John J. Trause

[box]It’s hard to believe that this is our FIFTH annual 30/30/30 series, and that when this month is over we will have seeded and scattered ONE HUNDRED and FIFTY of these love-letters, these stories of gratitude and memory, into the world. Nearly 30 books, 3 magazines, countless events and online entries later, and this annual celebration shines like a beacon at the top of the heap of my very favorite things to have brought into being. [If you’re interested in going back through the earlier 120 entries, you can find them (in reverse chronological order) here.]

When I began this exercise on my own blog, in 2011, I began by speaking to National Poetry Month’s beginnings, in 1966, and wrote that my intentions “for my part, as a humble servant and practitioner of this lovely, loving art,” were to post a poem and/or brief history of a different poet…. as well as write and post a new poem a day. I do function well under stricture, but I soon realized this was an overwhelming errand.

Nonetheless the idea stuck — to have this month serve not only as one in which we flex our practical muscles but also one in which we reflect on inspiration, community, and tradition — and with The Operating System (then Exit Strata) available as a public platform to me, I invited others (and invited others to invite others) to join in the exercise. It is a series which perfectly models my intention to have the OS serve as an engine of open source education, of peer to peer value and knowledge circulation.

Sitting down at my computer so many years ago I would have never imagined that in the following five years I would be able to curate and gather 150 essays from so many gifted poets — ranging from students to award winning stars of the craft, from the US and abroad — to join in this effort. But I’m so so glad that this has come to be.

Enjoy! And share widely.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/box]

[line][line]

DON ZIRILLI on JOHN J. TRAUSE

[line][script_teaser]“John challenges contemporary notions of what a poem is. He is a poet for both the optimist and the cynic. The optimist will be open to his difference, and the cynic is craving that difference. The only reader who is not for John is the complacent one, the reader who already knows what they want from poetry and is already getting it on a regular basis. It was only my vague dissatisfaction, a hungry curiosity, that gradually opened my mind to what John was doing.” [/script_teaser]

[line]

I want you to meet John J. Trause, and I want you to do it faster than I did.

John and I started out as pen pals. We were “set up” as correspondents by his cousin Chris when we were both at Drew University in the 80’s, and we sent each other poems. I resisted his poems at first, they didn’t fit my admittedly Romantic expectations. In other words, he didn’t write the sort of poem that Robin Williams would shout while standing on a desk.

John was getting his MA in Classics at the time, in Cincinnati. Later, he would get a Master of Library Science at Rutgers New Brunswick. Figuratively speaking, he’s not writing at a desk in his bedroom, or on the kitchen table, expressing or bemoaning an individual life. He’s writing in a giant arcade, filled with worlds within worlds, listening to the echoes of our earliest literatures.

John challenges contemporary notions of what a poem is. He is a poet for both the optimist and the cynic. The optimist will be open to his difference, and the cynic is craving that difference. The only reader who is not for John is the complacent one, the reader who already knows what they want from poetry and is already getting it on a regular basis. It was only my vague dissatisfaction, a hungry curiosity, that gradually opened my mind to what John was doing.

I’m hoping, perhaps naively, that you can skip all that resistance, trust me, and trust the poet. Ultimately, I’m asking you to trust yourself as a reader, trust the part of you that instinctively feels that something exciting is going on, something different.

As an example, let’s take a look at the first poem in his collection, Inside Out, Upside Down & Round and Round, called “In The Zoo.” On one level, it’s a simple, amusing story about a visit to the zoo, but if you approach it as an anecdotal poem and nothing more, it will seem flawed. My challenge to you is to explore those flaws, pry open the cracks in the veneer. Here are the opening lines:

[box]

On such a day as this in hot

July, when moistness slides around

Us everywhere as if alive,

And sunshine pours down like the rain

And moistens us the same, …

[/box]

5 lines into a 33-line poem and he’s still talking about the weather. Is the poet being merely indulgent, or just garrulous? If we trust the poet, if we assume it is deliberate, an explanation will appear. The iambic tetrameter, the internal rhyme (slide/alive, rain/same), the wet sibilants, and the slightly exalted diction might seem old-fashioned to your ear. But I think of it as good, if a little flashy, cinematography, setting the mood of a scene (the “flashiness” is a deliberate disturbance of the reader’s expectations, a cue that this poem is participating in something larger than one person’s afternoon).

[box]

…the place

To be for cool refreshment is

The Zoo in Philadelphia.

The zoo at feeding time among

The cats just at the peak of their

Ill humors and that space of time

When thoughts turn to the midday meal

Is where and when I found myself

With Jill this hot day in July,

Too hot to handle and too close.

[/box]

John’s second stanza would horrify most poetry workshops: the achingly passive phrasings spread out to an almost run-on sentence. Notice how aware he is of space, both physical and temporal: “the place to be” “at feeding time” “just at the peak of” “that space of time” “When thoughts turn to” “where and when I found” “this hot day”. It is to the point of absurdity, but it is also the point of the poem. Notice how it all seems to fight against the last line of the stanza, “Too hot to handle and too close,” as though he is pushing against the heat and proximity, however vainly. In fact, it’s this pushing that makes the reader more keenly aware of the oppressiveness, like the way you can gauge the intensity of the wind in a video by how much someone is leaning into it.

[line]

[articlequote]On such a day as this one tastes

the air. [/articlequote]

[line]

This couplet foreshadows the ending, and sets up a punchline behind the main punchline, but I’ll get to that later. For now, notice how the second line stops after one iamb. The rest of it is… air, as though he is giving you the chance (the space and time) to taste it (in a written poem, space can represent time, q.v. Olson’s projective verse). The passive, space-taking, space-making phrase, “On such a day as this” is repeated.

Only now, in this hot, humid, summer mood, does he plunge into the story:

[box]

Fat, quivering steaks were set for them,

The sexy cheetah, prancing in,

The slutty, sable panther, pards,

The testy, restive tiger tots,

The jaguar, leopard, ocelot,

And good, American cougar, each

Their slimy prey all set for them,

[/box]

This stanza, a robust list, would do well at the workshop, except maybe for the adjectives. One clever workshopper would inevitably tell John to start the poem here, but he would be wrong (as straw men always are). This poem doesn’t tell a story. The story that starts here is telling the poem. This feline parade is the madding crowd, too hot and too close, devouring the slime that is the “moistness” that is the day that is the world. They are the foil for our hero:

[box]

But in her cage the lioness

Named Agnes lay behind her steak

And licked and licked by increments

A path, immaculate, germ-free,

And didn’t pounce nor touch her steak

Until the space inside her cage

Around the steak was purified.

[/box]

As well as being a good joke, a lion named Agnes sets us up for the paradoxical nature of our hero. The name “Agnes” was mistakenly believed to mean lamb, and was given to Christian women to evoke the Lamb of God. Because the etymology is mistaken, Christ is really the only Lamb that this name signifies. So, more accurately than a lion named lamb, we have a lion named The Lamb, a lion with a Christian (Christ-like) name. Lamb and Christian: two of the most famous categories of lion victim. This living contradiction will fight “moistness” by licking (an even balder contradiction than Jesus washing away sins with blood).

[line]

[articlequote]Lustrational, …[/articlequote]

[line]

That’s not actually technically a word. It feels like a word (maybe someone stretching out in a relaxed and lascivious manner?), but it’s not the word it feels like. It’s really an improvised adjective form of “lustration,” which was originally a Roman sacrifice made every five years to purify the city. An animal sacrifice, to be specific (and here we are, at the zoo, looking for… redemption?). But the word is loaded with more contemporary meaning. It is associated with all sorts of political purges, like the denazification of Germany, the removal of Baathists from Iraq, etc etc etc. It can be something good, terrible, or both.

[box]

…she lay at least

Some seven feet behind her prey

And circumlicked her dining space.

It took a while; we watched her lick

And lick and clean and lick around.

Both Jill and I know Agnes well,

The obsessive-compulsive lioness.

[/box]

And here is the punchline, delivered calmly and authoritatively. Some will love the poem just for that, as it is a better joke than anything else they’ve heard that day. But, again, the poem isn’t telling a joke, the joke is telling the poem. The poem is itself obsessive in its detailed description of the obsessive behavior of the lion. This shows a certain reverence for, or at least complicity in, this obsession, and implies that something more than obsession is involved here: some sort of loving care, a sacred attention, and not something merely to be mocked. The poet thus honors the lion, and the lion honors the poetry, because they are both engaged in the same (il)lustration. But the poem isn’t quite done licking yet:

[line]

[articlequote] On such a day as this one tastes

the air. Too hot to handle, and

too close.[/articlequote]

[line]These repeated lines seal the deal. The poet must finish his ritual, is compelled to do so. Notice how the hanging “the air” disrupts the other phrase, so that “too close” is now hanging out by itself. In a way, the obsessive compulsion has solved the original problem. The phrase “too close” has been given air. The extra space at the end of the line feels like a breath of relief from an OCD sufferer completing his ritual.

But I still haven’t gotten to the punchline behind the punchline that I mentioned before. To get there, we must return to the top of the poem, where there is an epigraph (that I neglected to mention until now):

[articlequote] ex ungue leonem [/articlequote]

which means, “from the claw, the lion.” Bernoulli used that phrase to explain how he knew that Newton was the author of an anonymous mathematics solution. So there’s a self-deprecating joke here, that the author of the poem is as OCD as the lion he writes about… but there is also a still larger joke, that the Author of the Universe is OCD. He is in “the air,” His careful licks are the sliding “moistness” “as if alive.” Especially when one reads more of John, one realizes that this poem is an assertion of faith in an orderly, ordered Universe.

I hope all this analysis hasn’t made you think the poem is merely clever, or, even worse, a homework assignment. The poem is as essential, as critical, to the poet as a claw is to a lion, or as Ariel is to Sylvia Plath.

However, if you think you’ve got a grasp of the poet now, you may be disappointed. His work is so varied that no one poem can epitomize it. He is visual, he is conceptual, he is perverse. He compares the fattest living man to a dormouse and a serial killer to the Madonna. He translates a sonnet into its punctuation. He writes poems in Morse Code, the international phonetic alphabet, and geometry. He sees no point in writing a poem that is similar to a poem he’s already written. He wants every poem to challenge you, because he is challenging himself.

His greatest influence on me as a writer was to fill me with doubt and possibility at the same time, because he shows me that there is no single path to a poem, that each poem is its own path. The title of his latest book is also an ars poetica: Exercises in High Treason. The main theme is translation (and the impossibility of true translation), but in all of his work he plays the traitor, working against expectations put on poetry.

Both Inside Out, Upside Down & Round and Round and Exercises in High Treason are major, wide ranging collections of John’s poetry. Either one or both would make an excellent introduction to his work. What I did in 30 years, you could do in a single book: Fight the genius, hate the genius, give in to the genius, love the genius. Repeat until hopeless.

[line]

[box] ENDNOTE: As is sometimes the case, our subject got a chance to read this piece and sends the following additional notes, on “Inside the Zoo”:

— You may want to consider “Inside the Zoo” as a modern type of pastoral and that “On such a night as this…” has a pedigree going back to Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice Act V, Scene 1 through Anne Finch, Countess of Winchelsea and her “A Nocturnal Reverie”.

— The name Agnes derives from the Greek name Ἁγνὴ (hagnē), meaning “pure” or “holy” or even “(ritually) clean”. It was associated by Latin-speaking Christians with agnus, the word for “lamb”, but that is only a side note. The coincidence and joke is that a ritually pure lioness is named Agnes.

You’ll be hearing more from John soon – he also wrote a piece for this series, on the Baroness Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven. [/box]

[line][line]

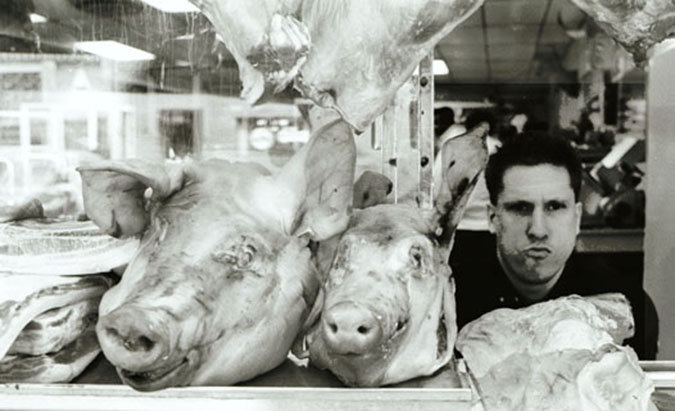

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/DSCF4041crop.jpg[/textwrap_image] By day, Don Zirilli is a director of web programming for a healthcare informatics company. Most of the rest of the time, he is writing poetry, taking photographs and making art. He has a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature from Drew University. His poetry has been published in River Styx, Art Times, Specs, Anima, Iota, Antiphon, and other literary magazines and anthologies. He was the editor of Now Culture, a journal of literature and arts, in addition to being the art editor of The Shit Creek Review. Last year, his painting served as the cover of theRed Wheelbarrow poetry anthology, in which he was also the featured poet. Don and his wife, Colleen, live in Tranquility, New Jersey, with 2 dogs and 3 cats.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]