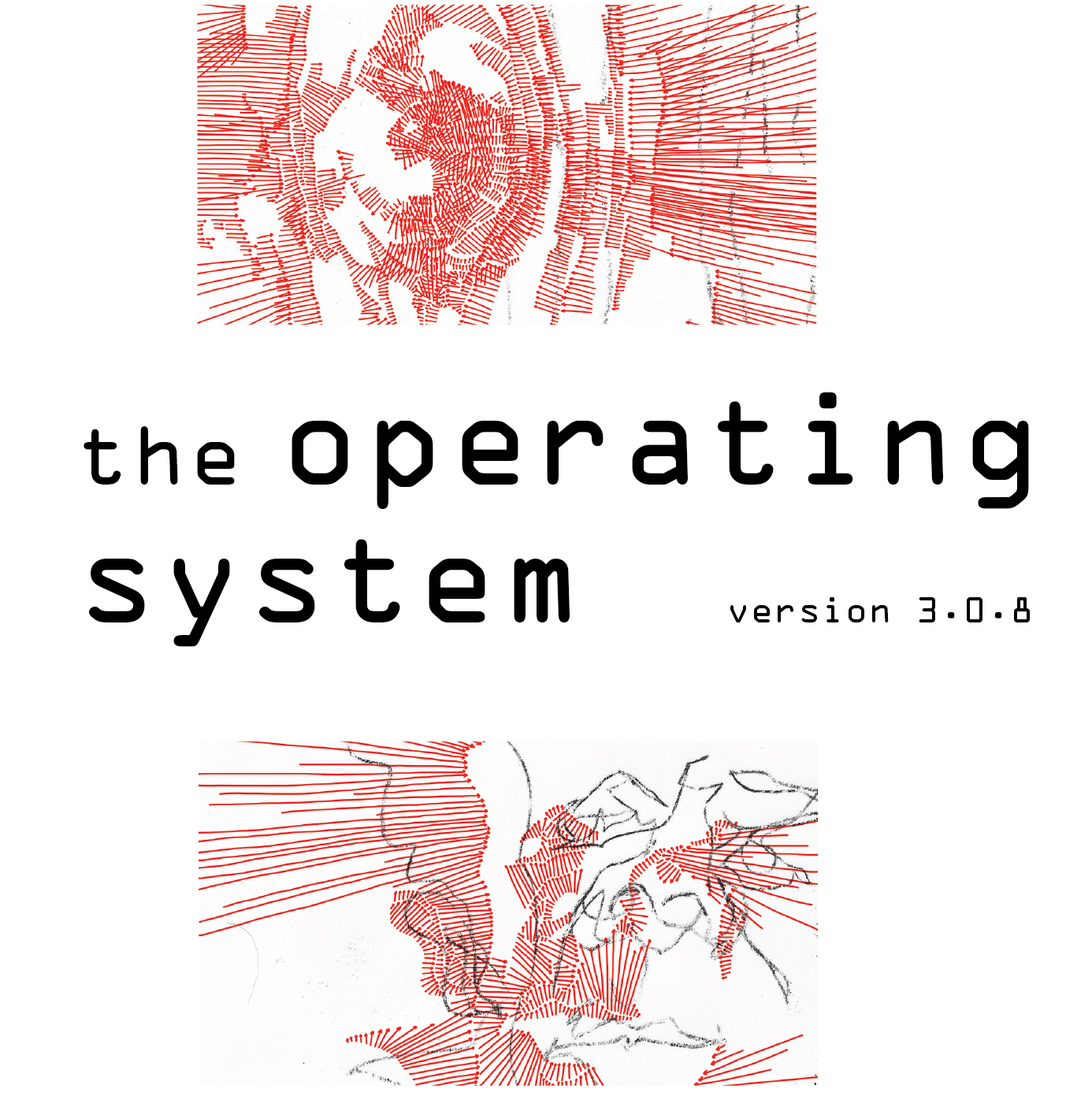

5th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 9 :: Sam Selinger on Wallace Stevens

[box]It’s hard to believe that this is our FIFTH annual 30/30/30 series, and that when this month is over we will have seeded and scattered ONE HUNDRED and FIFTY of these love-letters, these stories of gratitude and memory, into the world. Nearly 30 books, 3 magazines, countless events and online entries later, and this annual celebration shines like a beacon at the top of the heap of my very favorite things to have brought into being. [If you’re interested in going back through the earlier 120 entries, you can find them (in reverse chronological order) here.]

When I began this exercise on my own blog, in 2011, I began by speaking to National Poetry Month’s beginnings, in 1966, and wrote that my intentions “for my part, as a humble servant and practitioner of this lovely, loving art,” were to post a poem and/or brief history of a different poet…. as well as write and post a new poem a day. I do function well under stricture, but I soon realized this was an overwhelming errand.

Nonetheless the idea stuck — to have this month serve not only as one in which we flex our practical muscles but also one in which we reflect on inspiration, community, and tradition — and with The Operating System (then Exit Strata) available as a public platform to me, I invited others (and invited others to invite others) to join in the exercise. It is a series which perfectly models my intention to have the OS serve as an engine of open source education, of peer to peer value and knowledge circulation.

Sitting down at my computer so many years ago I would have never imagined that in the following five years I would be able to curate and gather 150 essays from so many gifted poets — ranging from students to award winning stars of the craft, from the US and abroad — to join in this effort. But I’m so so glad that this has come to be.

Enjoy! And share widely.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/box]

[line][line]

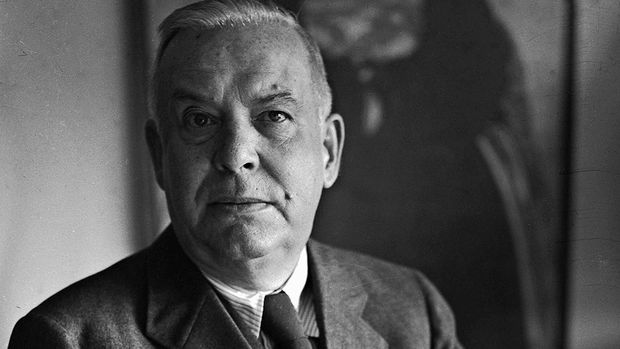

SAM SELINGER on WALLACE STEVENS

[line][script_teaser]”Stevens is the poet I turn to for our most deeply felt and least understood experiences, the ones we have the fewest words for, and the ones we need poetry for most, the experiences that in a less ironic age we would have called the sublime.”

[/script_teaser]

[line]

There are other poets I have turned to somewhat more in regard to how to write poetry, particularly John Ashbery and William Carlos Williams, and some more contemporary voices like Joshua Beckman and Mei-Mei Bersenbrugge. But Wallace Stevens has always been for me the poet I turn to in understanding why to write poetry.

That is not to say that the how of Wallace Stevens’ poems is not miraculous. When I first began reading him, I was stunned at his ability to turn a phrase, and I still am. The way he can pack utterly singular and witty wording, philosophical play and deep pathos into a single line is almost awe-inspiring:

[line]

[articlequote]“nothing that is not there and the nothing that is;”

“She sang beyond the genius of the sea; ”

“her terrace was the sand and the palms and the twilight;”

the arctic north “With its frigid brilliances, its blue red sweeps

And gusts of great enkindlings, its polar green,

The color of ice and fire and solitude.” [/articlequote]

[line]

In some regards, my Wallace Stevens does not always resemble other people’s Wallace Stevens. Other people I know describe the experience of reading a Stevens poem as a sort of lighthearted but cerebral exercise in philosophy, metaphysics or strange wordplay, the Stevens of “The Emperor of Ice Cream,” or “Bantams in Pine-Woods.” And, to be certain, this is always a part of any Stevens poem. But for me Stevens is the poet I turn to for our most deeply felt and least understood experiences, the ones we have the fewest words for, and the ones we need poetry for most, the experiences that in a less ironic age we would have called the sublime.

When my grandmother died I suddenly understood “The Owl in the Sarcophagus,” and it understood me also. When my friend took his own life last year only “Final Soliloquy of the interior Paramour” seemed to grasp the stakes of it, and the kind of meanings we are forced to try and invent, not because we necessarily believe them, but because they will do. When I was confronted with the vast night skies under the long plains in Wyoming two years ago, I suddenly heard phrases from “The Auroras of Autumn.” When I have been greeted with tragedy on the news, as happens all too often these days, I turn to “Chocorua to Its Neighbor” or “Esthetique du Mal,” or to Stevens’s most famous aphorism about poetry—it is the imagination pushing back against the pressures of reality.

At first, I thought I would close read either all of or an excerpt from one of the poems I mentioned above, or perhaps from another one of his odd and yet somehow also magisterial longer poems, such as “The Man With the Blue Guitar,” or “To an Old Philosopher in Rome.” But then I remembered a very short, early, lesser-known poem of his called “Fabliau of Florida:” [line]

[box]

Barque of phosphor

On the palmy beach

Move outward into heaven

Into the alabasters

And night blues.

Foam and cloud are one,

Sultry moon-monsters

Are dissolving.

Fill your black hull

With white moonlight.

There will never be an end

To this droning of the surf.

[/box] [line]

This was the first poem for which I had the experience that I memorized it without trying. One day it was simply there in my mind, in its totality. I think it was the catchy, deceptively metered cadence of it, and the sort of hypnotic quality to the way the words move that made it stay there. It was years before I wondered exactly about what the words meant; it almost didn’t matter. When I did finally sit down and attempt to understand the poem, I realized the sounds center around a single image. “Barque,” I quickly learned from the dictionary, is an archaic word for a boat or ship. The “barque of phosphor” that “moves outward into heaven” is a small, empty wooden boat, being pushed out to sea. It’s a simple, meditative image that feels almost religious, although I have never been able to put my finger on why. Despite, or even because of, the quintessentialy Stevens silliness of “sultry moon-monsters,” I have come to think of the poem as a sort of hymn.

To understand how this high seriousness and his strange, metaphysical sense of humor can come together in one poet is to grasp the ethics of Wallace Stevens. To some extent, even though I have been reading Stevens for years, it was only until recently that I fully understood this. And, in part, I had to read some other literature, in particular Jerome Rothenberg’s magnificent anthology Technicians of the Sacred, a collection of oral poetries from indigenous peoples around the world.

Stevens was not merely a Connecticut insurance salesman who was a strange modernist poet underneath. He was a Connecticut insurance salesman who was a strange modernist poet underneath, and underneath that he had the ambitions of an epic poet from a pre-modern or pre-scientific age. For millennia, in cultures from every corner of the globe, the work of the poet, and the work of the imagination, was the work of meaning-making, to give a story to everything from the origins of the cosmos to the workings of the weather to nature of death to the strange workings of love to the inexplicably brutal ways people can treat each other. In Imagination and The Meaningful Brain, Arnold Modell considers psychological and neuroscientific theories that look at the need to make meaning and metaphor as a biological necessity. Poets from the beginning were in the business of making existence meaningful, and the meaningful taken to its logical conclusion becomes the sacred. [line]

[articlequote]At a time when science was beginning to look into space and see nothing there, and the human being had become inextricably a technological creature with all of the terrible destruction that accompanies it, Stevens turned to the poem as the last place where one could still hear the imagination confronting the bare brute facts of existence and making a life out of them. [/articlequote] [line]

When Stevens wrote, we had just truly realized that we were hopelessly modern and that there was no turning back. His poems (particularly in Transport to Summer) rarely explicitly mention that World War II is occurring as he is writing them, but it is there and implied in every poem. At a time when science was beginning to look into space and see nothing there, and the human being had become inextricably a technological creature with all of the terrible destruction that accompanies it, Stevens turned to the poem as the last place where one could still hear the imagination confronting the bare brute facts of existence and making a life out of them. What Stevens understood is that in the modern world, the only way for many of us to find a transcendent belief is through make-believe– we may no longer believe the mythological or religious or spiritual stories or poems but it is through the imaginative act of inventing them that we can continue on. The answer, says Stevens, is to believe in a fiction while simultaneously knowing it is a fiction. Without being sentimental or grandiose or backward-looking or religious (often quite anti-religious), Stevens conceived of a modernist poetry where, even in the modern world, one might find something sacred.

Of course Stevens’ time is not our time. The modernity he attempted to reconcile the imagination to seems almost quaint and retrograde now, and perhaps sometimes his poems even might seem that way to the contemporary poet or reader of poetry. The ethics I write about, the individual armed only with his idiosyncratic imagination reconciling himself the brute facts of reality and the cosmos, may seem equally quaint and old-fashioned in our hyperconnected age of social commitment and political stance-taking, not to mention an age where the whole notion of the “individual” has become co-opted by the right wing as a buzzword for corporate free reign and evading any responsibility for others. But, unfashionable as it might be, I believe Stevens’ poetic commitment has the potential to speak to our time also. I know that I am still trying to write “The poem of the mind in the act of finding/ What will suffice.” In fact, I think I will finish with the whole of that poem, called “Of Modern Poetry,” and challenge anyone to say that this doesn’t still speak to the ideal of what we are trying to accomplish as poets.

[box]

The poem of the mind in the act of finding

What will suffice. It has not always had

To find: the scene was set; it repeated what

Was in the script.

Then the theatre was changed

To something else. Its past was a souvenir.

It has to be living, to learn the speech of the place.

It has to face the men of the time and to meet

The women of the time. It has to think about war

And it has to find what will suffice. It has

To construct a new stage. It has to be on that stage,

And, like an insatiable actor, slowly and

With meditation, speak words that in the ear,

In the delicatest ear of the mind, repeat,

Exactly, that which it wants to hear, at the sound

Of which, an invisible audience listens,

Not to the play, but to itself, expressed

In an emotion as of two people, as of two

Emotions becoming one. The actor is

A metaphysician in the dark, twanging

An instrument, twanging a wiry string that gives

Sounds passing through sudden rightnesses, wholly

Containing the mind, below which it cannot descend,

Beyond which it has no will to rise.

It must

Be the finding of a satisfaction, and may

Be of a man skating, a woman dancing, a woman

Combing. The poem of the act of the mind.

[/box]

[line][line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/FullSizeRender-2-e1459884787498.jpg[/textwrap_image] Sam Selinger’s work has been published in Bat City Review, Grey Magazine, Lotus Eater, Explosion-Proof, and elsewhere. He recieved his MFA from New York University in 2014, and is currently in graduate school to become a clinical psychologist. He was handed the 30/30/30 torch by Peter Longofono.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]