5th ANNUAL NAPOMO :: BONUS! DAY 31 :: NOMI STONE on PRODUCING AWE and TERROR in the POEM

[box]It’s hard to believe that this is our FIFTH annual 30/30/30 series, and that with this bonus post we will have seeded and scattered ONE HUNDRED and FIFTY (ONE!) of these love-letters, these stories of gratitude and memory, into the world. Nearly 30 books, 3 magazines, countless events and online entries later, and this annual celebration shines like a beacon at the top of the heap of my very favorite things to have brought into being. [If you’re interested in going back through the earlier 120 entries, you can find them (in reverse chronological order) here.]

With Nomi Stone’s piece today we venture digitally into a realm you’ll see more of from The OS in the months and years to come — The OS as pirate library: space for the publishing, open-source archiving, and distribution of texts that might normally get stuck behind academic paywalls, might never leave the classroom, might get edited or languaged into oblivion by the ontological powers that be, and crucially, might never reach the public. Some of these may appear anonymously, to protect those who wish to distribute their work, but without threat to their tenuous non-tenure.

Stone’s full text is available as a downloadable PDF, for personal or classroom use. Others will appear as physical pamphlets, available for free or cheap at bookfairs to come. Stay tuned.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/box]

[line][line]

PRODUCING AWE and TERROR in the POEM:

TREMBLING AWAKE IN THE WORKS of GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS, JORIE GRAHAM, and PAUL CELAN

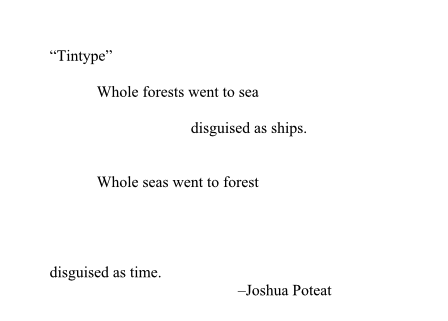

[line][script_teaser]The forests process into the sea. Watch the treetops amidst the crests. No: they are vessels, or masquerading as vessels. Wait: reset. Whole seas are swallowed within the forest, crumbling into infinity. The imagination batters against Poteat’s propositions, producing an exquisite vibration between awe and terror. Can the world’s immensity be rendered and what tools are available? [/script_teaser][line]

[box]

In the American South, a soldier is roasting a pig on his porch until its sinews are tender. I have been interviewing him for years and again he is telling me stories about Iraq. The American occupying forces warned the Iraqi population to remain within Baghdad while homes were searched. But many of them tried to cross the Euphrates River in the middle of the night. The soldiers waited above the bridge. “We told them not to,” he tells me. But they crossed, in droves, slicing through the black water in the blackest hour of the night (“Whole forests went to sea”). “We told them not to” (“Whole seas”) — “they were asking for it” (“to forest”). This is the sensation as the tiny bullet enters the tiny body in the black night (“Disguised as time”). Something has happened, but the interior cannot carry it; the imagination cannot bear it. Poteat knows this; he renders the impossible moment as a tintype, an image on dark lacquered metal: it is a human portrait of awe. That is, it is the winnowing of the experience into our representation of that experience.

[/box][line]

[line]

[box] What appears below are excerpts of Nomi Stone’s full text, alongside the poems of Hopkins, Graham, and Celan that inspired her writing. We’ve included these paragraphs to allow you to enter into the space of her inquiry in a shorter time frame, but encourage you to download and read the PDF at your leisure. [/box][line]

Introduction

According to Immanuel Kant, it is not simply the exterior phenomenon in the world but our struggling interface with it, which creates the sublime experience. For Kant, the Imagination’s inability to wholly access a phenomenon produces a fluctuation between pleasure and pain. Yet ultimately, in his Enlightenment construct, the “sublime” experience produces the “momentary checking of the vital powers and a consequent stronger outflow of them” (102). In this outflow, the painter ultimately captures the mountain in his frame; the atrocity in Iraq can be rendered. I am inspired here by Kant up to a point. The poems herein are far less about heroic arrival points and more about the trembling work of finding the tools to make the experience the poet feels resonate through the body of the reader.

I examine here how awe and terror are produced in the poem, examining sonic qualities in Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “The Windhover,” syntax in Jorie Graham’s “Mother and Child (The Road at the Edge of the Field),” and negation in Paul Celan’s “Psalm.” In Hopkins, I look at how sonic plosions and dizzying breath work in tandem with a potentially multiple metaphor to create the sublime. In Graham, I show how the prolonged and indeterminate winding of syntax creates an equally wonder-trembling height. And, in Celan, I show how the void itself, and the manipulation of negation, might bring the reader to a similar nearly unspeakable location.

[articlequote]The poem in each case is a heady negotiation between the most virtuosic mastery of craft and a mounting sensation that seems to nearly exceed language. A phenomenon in the world exceeds itself, becoming the all. The violence of loss threatens to devour beauty. In the aftermath of catastrophe, the forsaken world burns the glow of nothing awake. [/articlequote]

Furthermore, in each case, the catalyst for the sensation is enormous, multifoliate: it can neither be read nor rendered in a single way. Rather, there is uncontainability, multiplicity and ambiguity: our imaginations are exceeded, we silver the sublime for a moment into our tintypes.

[line]

[line]

[line][box]

The Windhover

To Christ Our Lord

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

…dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

…Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

…As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

…Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

…Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

…No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

…Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.

[/box][line]

Sonics in Gerard Manley Hopkin’s “The Windhover”

In his journal in 1871, Hopkins wrote of the “inscape”: an entity of “simple and beautiful oneness” that floods the observer, suggesting the object’s divine fashioning (520). He described the “instress” as the process by which the observer perceived the inscape. He explains this movement: “I saw the inscape…freshly, as if my eye were still growing” (Greene, Cushman, and Cavanagh 708). “The Windhover,” through its sonic percussion (irregular meter, rhythm, assonance, consonance, modulation of breath) and its metaphoric multiplicity, progressively positions us within that exhilarating instress around the glow of a bird. I trace here how wonder and awe are produced in the process, as the bird expands into a manifestation of the all: at once, the godly and ever-living; the human and the ever-dying.

The poem is called “The Windhover,” referring to a kestrel, a kind of small falcon that beats its wings rapidly, facing into and aloft upon the wind. It is dedicated to “Christ our Lord,” preparing the reader for the possibility of (but not necessitating) the metaphorizing of the bird to the divine. The first line of the poem is in regular iambic pentameter, offering the most recognizable of rhythms. Yet, still, the line estranges and astonishes the ear, through the use of a combination of wild sonic explosions and percussive stresses.

[line][articlequote]From the outset of the poem, Hopkins locates the bird as a manifestation of divine creative capacities on the earth: in this sense, the bird like Christ is an iteration of God — but, implicitly, so is every embodied phenomenon in the lower world. For me, as the poem progresses, all adjacent phenomenon of the earth — ocean, trees, and our own bodies, become animated proof of the electric force that binds them. [/articlequote][line]

Hopkins continuously uses sonic tools to enlarge our imaginative and metaphorical possibilities for the bird. Indeed, Hopkins is attuning us not only to his masterful assonance and consonance, but also to an additional kind of sonic pleasure — the susurration of the reader’s breath itself, trying to keep pace. This syllabic unfurling as the breath works alongside it might be felt as the work of Hopkins’ “instress” in its movement towards the inscape: that is the active enlargement of the eye and consequently the mind of the reader, around the windhover.

Only four lines into the poem, metaphor opens, showing its multiplicity, in tandem with Hopkins’ sonic work. Likewise, when an instrument is played, columns of air vibrate and then produce sensation in the listener: that sensation, in this instance, is the awe produced by a bird becoming multifoliate in our imaginations.

Indeed, the poem is a heady negotiation between the most careful mastery of craft through tools of language (virtuosic sonic invention; a new meter that made breath itself vertiginous) and a mounting sensation of awe that seems to nearly exceed language.

[line]

[line]

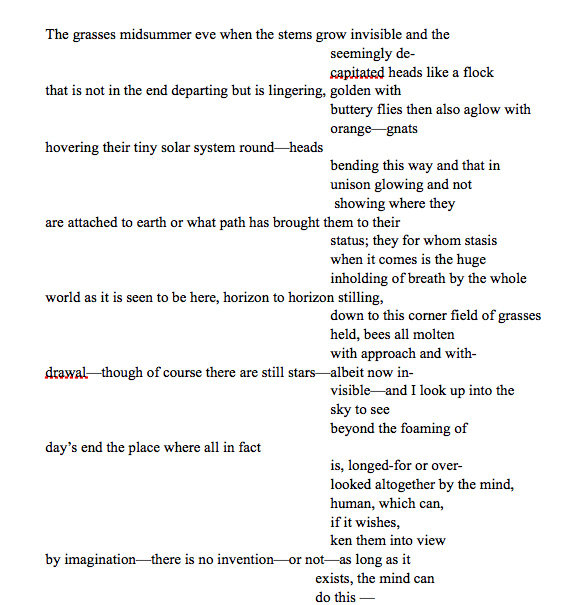

Mother and Child (The Road at the Edge of Field)

[Excerpt, full text in pdf]

Syntax in Jorie Graham’s “Mother and Child (The Road at the Edge of the Field)”

While Hopkins’ primary tools for generating the sublime were sonic, Jorie Graham equally masterfully manipulates syntax to similar effect. As in the case of Hopkins, Graham tests and extends the parameters of what the reader can carry within their own interior, while bringing awe and terror, and beauty and violence, into trembling interface. In “Mother and Child (the Road at the Edge of the Field),” Graham positions her readers amidst the tendrils of grass, in an ever-modifying sentence, which lasts across 120 lines. The dizzying additions she adds leave the reader in a state of near vertigo, awaiting, and bracing for, an uncertain predicate. The poem’s first sentence reads as a continuously billowing-open dependent clause, which finally seems to possibly, ambiguously land. The final lines of the poem, composed of short independent clauses, act as the syntactic and emotive fulcrum of the poem: gathering the sensation into a moment of sublime intensity. In addition, Graham also controls and accelerates moments of awe through her shifting use of pronouns, image, and metaphor, which I discuss along the way.

[line][articlequote]The poem enacts the inholding of breath, an intensifying waiting. Indeed, one of Graham’s characteristic moves, the breaking of a word into charged constituent parts, also comes to the fore in her enjambment of the word “in-/visible.” In this instance, the “in’s” prepositional and negational meanings are preserved, a reinforcement of the sensation of inholding of breath. Yet, at the same time, by breaking the word in this manner, the stasis of the moment is both “visible” and “invisible” at once: a charged duality and ambivalent that holds the reader taut.[/articlequote][line]

This moment of almost-pause is immediately counteracted with the poem’s essential and ongoing tug: between the billowing forward towards the predicate and the push back, to assimilate the growing heft of image into our seeing of the field. Syntax, enjambed line, alternating line length and image together collaborate to create this sensation, where we are made dizzy in our apprehension of the world.

[line]

[line]

[box]

“Psalm” by Paul Celan, Translated by Michael Hamburger

No one moulds us again out of earth and clay,

no one conjures our dust.

No one.

Praised be your name, no one.

For your sake

we shall flower.

Towards

you.

A nothing

we were, are, shall

remain, flowering:

the nothing-, the

No one’s rose.

With

our pistil soul-bright,

With our stamen heaven-ravaged,

our corolla red

with the crimson word which we sang

over, O over

the thorn.

[/box][line]

Negation in Paul Celan’s “Psalm”

Hopkins conjured the internal crescendos inspired by a bird that was ever more than bird, a lower manifestation of the upper world; and Graham traced the awe and terror of this one world’s savage beauty. Both began with the world’s profusion stabbing into the speaker’s seeing. Celan’s rendering of the sublime begins instead from a forsaken and retracted world. In “Psalm,” Paul Celan uses negation and markers of temporality, as well as the tension of the line, to induce a sensation where the world blooms furiously and paradoxically through its very unpetaling. I make use of the translation of John Felstiner, supplementing it in moments of ambiguity with Michael Hamburger’s translation in order to arrive more closely at Celan’s original poem. Thus, all instances where the poem is quoted are Felstiner’s translation, unless otherwise specified. Celan positions the reader in an inversion/ reinvention of two sacred genres: the psalm and the creation story. The genre of the psalm classically acts as a sanctification of god: either through a benediction or lamentation, faith of god is reaffirmed. The creation story narrates the emergence of the cosmos, as the roiling unities, that which is “formless and empty” separate: “he separated the light from the darkness” (Genesis 1:3). As the poem unfolds, I am reminded of Theodor Adorno’s post-Holocaust Earth that is “radiant with triumphant calamity” after an ever-illuminated earth became an engine of the obliteration of life (2002 1). In this poem, instead, the work of “nothing” and “no one” carries us back into the cover of the soil, into our first bright seed, a terrifying mental act that requires the reader to winnow away the all into bareness.

God cannot create mankind again. The use of the temporal marker “again” is crucial here: at one time, there was an origin — humanity was sculpted out of the depths, an act of hope. However, in this instance, the agent is revoked. The effect here, of the iteration of the act only through its withdrawal and impossibility, creates something like the flare of light from that which is absent.

[line][articlequote]We come to understand that the very condition of being human now — in a newly broken world — is an unfolding into and out of the Nothing; that is the bloom we are left with and the bloom we must paradoxically learn to embrace.[/articlequote][line]

Celan englobes the selves spanning all times and conditions: the self of the past and present and the ever-more self of all imaginable futures, are all borne together into the Nothing. Effectively this temporal move creates a collision of infinities: alltimes, allselves, are simultaneously submerged into the condition of Nothing: this move creates a mental pivot so dizzying that the reader can hardly catch up: a sensation of imaginative excess that the human mind cannot contain.

Yet just when it appears this intensity has reached a new height, Celan brilliantly pivots, with the word “blooming”— into yet an even more profound pinnacle in the poem. This fourth line of this third stanza ends with a colon, a pause in the work of the line, allowing us to imagine that the lines that come subsequently are the very bloom itself. We come to understand that the very condition of being human now — in a newly broken world — is an unfolding into and out of the Nothing; that is the bloom we are left with and the bloom we must paradoxically learn to embrace.

Our pistil is bright, our stamen is of the firmament — and both these things might be directly a cause of and emergent from the purpleword, a word dunked in the dark of living (“our corona red/ from the purpleword”).

[line][articlequote]in each poem, the world dwarfs us: the world’s mountains and fish and birds and green fields and burnt fields and even its black voids, its love and tenderness and hope, its nourishing of and then brutal undoing of every living thing — come first. We cannot hold all of that world inside our bodies. That trembling awake is the sensation of the poem not holding it — holding it — not holding it.[/articlequote][line]

[line][line]

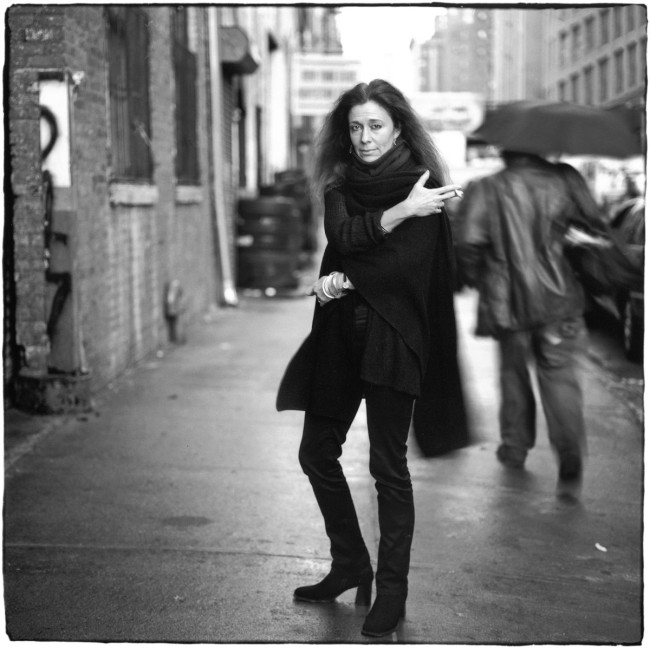

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Stone-headshot-e1462110331335.jpg[/textwrap_image] Nomi Stone is the author of the poetry collection Stranger’s Notebook (TriQuarterly 2008), an MFA Candidate in Poetry at Warren Wilson and a PhD Candidate in Anthropology at Columbia. Poems appear or are forthcoming in The New Republic, The Best American Poetry 2016, The Best Emerging Poets 2014-15, Guernica, Poetry Northwest, and elsewhere. She is currently working on Kill Class, a collection of poems based on her fieldwork within war games across America, and she will begin a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship at Princeton in the fall.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]