6th ANNUAL NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: DAY 9 :: RAQUEL SALAS RIVERA ON ÁNGELA MARÍA DÁVILA’S 'ANIMAL FIERO Y TIERNO'

[box][blockquote]HAPPY POETRY MONTH, FRIENDS AND COMRADES!

For this, the 6th Annual iteration of our beloved Poetry Month 30/30/30 series/tradition, I asked four poets (and previous participants) to guest-curate a week of entries, highlighting folks from their communities and the poets who’ve influenced their work.

I’m happy to introduce Janice Sapigao, Johnny Damm, Phillip Ammonds, and Stephen Ross, who have done an amazing job gathering people for this years series! We’re so excited to share this new crop of tributes with you. Hear more from our four guest editors in the introduction to this year’s series.

Hungry for more? there’s 150 previous entries from past years here! You should also check out Janice’s piece on Nayyirah Waheed, Johnny’s piece on Raymond Roussel, Phillip’s piece on Essex Hemphill, and Stephen’s piece on Ronald Johnson’s Ark, while you’re at it.

This is a peer-to-peer system of collective inspiration! No matriculation required.

Enjoy, and share widely.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/blockquote][/box]

[line][line]

[box] WEEK TWO :: CURATED BY JOHNNY DAMM

PROPOSITION:

Every time a WRITER sees another WRITER on the street, WRITER # 1 yells the following question:

“Who are you reading?”

WRITER # 2 answers, also yelling, and at the first word, EVERYONE on the street stops walking, presses hands over mouths of cooing/crying babies, slams down car brakes and hurriedly unrolls windows.

EVERYONE listens, the world not allowed to resume until WRITER # 2 stops yelling.

SMALL REVISION:

Keep everything exactly the same, except make sure that WRITER # 2 is a talented writer, a fascinating writer, that WRITER # 2 is the present or future of what literature should be.

PROPOSITION:

Hush, y’all. Listen as Colette Arrand, Stephen Emmerson, Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, E.G. Cunningham, Douglas Luman, Travis Sharp, Raquel Salas Rivera, and Terri Witek yell into the street. [line]

Johnny Damm is the author of Science of Things Familiar (The Operating System, 2017) and three chapbooks, including Your Favorite Song (Essay Press, 2016), and The Domestic World: A Practical Guide (Little Red Leaves, forthcoming). His work has appeared in Poetry, Denver Quarterly, the Rumpus, Drunken Boat, and elsewhere. Visit him online at johnnydamm.com. [/box]

[line][line]

RAQUEL SALAS RIVERA ON ÁNGELA MARÍA DÁVILA’S ANIMAL FIERO Y TIERNO

[line][script_teaser]To be of the book is to become the nameless animal that lives between signs, and to assume the precariousness of an identity that is always becoming through the shared anonymity of collective loss.[/script_teaser]

[line]

I inherited a copy of Animal fiero y tierno¹, from my grandfather, the poet Sotero Rivera Avilés. It was part of a literary patrimony that ended with my queer, trans, infertile body: una hoja de yagrumo. Along with it came a mythology: stories upon stories about a working class black man who was wounded and almost died fighting for the country that colonized us, and came back to Puerto Rico a disabled poet. These were stories about the diaspora, return to a homeland, the building of a nuclear family, and the dreamt reconstruction of a fragmentary masculinity. They came to define poetry as a daunting project, a male, cis and heterosexual greatness born out of struggle. Poetry was the nation, the revolutionary figure that bore the collective burden, as he cut open a path towards the river.

Animal fiero y tierno was the river itself, the lizards, the moss, the mulch, everything outside that lineage and somehow part of a story I’d never heard. It took place simultaneously, in the same, now unrecognizable, forest, and was about those of us who were left outside of poetry’s greatness, but embraced by poetry’s diminutive anonymities. Published by queAse in 1977, this was Ángela María Dávila’s (Anjelamaría Dávila) second poetry book, but the first book she wrote without her husband, the poet José María Lima; yet, this statement is in some ways misleading, since the book continually undermines her authorial role, attributing its production to the voices of countless poets, political figures, family members, and unnamed sources, making it impossible to conscribe it within narratives of continuity or rupture. Written during the years in which she gave birth to and began raising her son, it offers him, her, and the readers an alternative to what Juan Gelpí has called Puerto Rico’s “paternalist” literary discourse.²

The book’s skin is composed of permeable boundaries or “frontera[s] con el aire” (“frontier[s] with the air”)³ that demarcate but do not exclude. Multiple voices echo within its intermittent frame, where the reader must choose whether to participate by lingering in the lacunas of shadowy, wet places, dark niches where the crying begins even before the crier can be named. There, the answerer—who is not a principal voice but an open subject that is searching for her “estirpe” (“lineage”)—learns to make alliances, responding to hostile voices through hopscotched multiplicity. To be of the book is to become the nameless animal that lives between signs, and to assume the precariousness of an identity that is always becoming through the shared anonymity of collective loss.

[line]

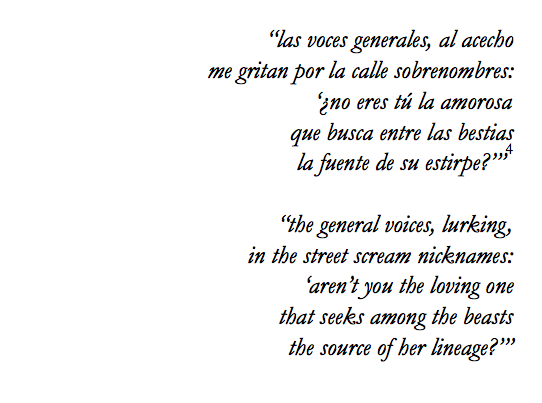

Dávila combined pictographic images; the suppression of capitalization and titles; large areas of blank space; the division of the book in regions; and phonetic spelling, in conjunction with more standardized syntax, lineation, and punctuation. This helped her articulate artifice and estrangement as intimacy. She also layered multiple voices by combining italics and quotation marks. We see this in the “autodedicatoria” (“self-dedication”) that prefaces the book’s decentralized body:

[line]

[line]

When the “general voices” scream the “nicknames” at the principal voice, it is not a one-word—which would shorten a long name—but rather a two-word sobriquet that converts the adjective “amorosa” (“loving”) into “la amorosa” (“the loving one”) by adding the definite article “la” (“the”); but when read them out loud, both words become one through a synalepha: lamorosa. The poetic voice is and is not singular. The difference (or lack thereof) between the written and the oral signs, allows Dávila to foreground both singularity and multiplicity of the speaking subject. Language becomes oral in the written/ written in the oral/ aural in the written/ written in the aural/ aural in the oral/ oral in the aural/a (singular) in the oral (plural)…

Phonetic unification also reveals a second nickname. La amorosa is also la morosa, she who acts slowly, in a state of perpetual delay. In a second translation, “‘“¿no eres tú la amorosa/que busca entre las bestias/la fuente de su estirpe?”’” becomes “‘“aren’t you the delayed one/that seeks among the beasts/the source of her lineage?”’” This is the temporality that prefaces Animal fiero y tierno, one that already prepares the reader for queer time, for stops, and derailments.

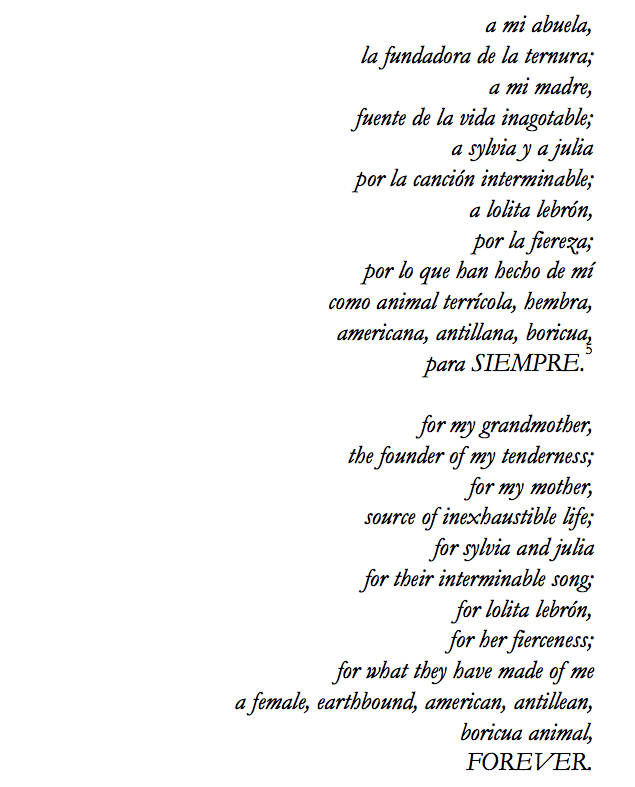

The self-dedication is dated “1969”, seven years before the date on the dedication and one year before the book’s publication. Dávila leaves this clue so that the reader can infer that after being confronted by the “voces generales” (“general voices”), the primary speaker went on a journey in search of “la fuente de su estirpe” (“the source of her lineage”) and returned with the “dedication” as an answer:

[line]

Dávila establishes her own matrilineal lineage. Instead of envisioning herself as a branch of the patertree, she creates what throughout Samuel Delany’s novel Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand are called “streams.” The women that make up these streams do not leave capital as inheritance, they leave “tenderness,” “inexhaustible life,” “interminable song,” and “fierceness”.

In Escritura afropuertorriqueña y modernidad, Eleuterio Santiago-Díaz explores the relationship between the ellipsis, the eclipse, and constructions of racial discourse in Puerto Rican literature. He outlines how official discourse defines the ellipse as the suppression of a something voidable, unnecessary, or excessive in relation to a core signification. In fact, some ellipses are accompanied by the three suspension points, concluding that the ellipsis does not just “suppress” it also “suspends,” “hangs,” and almost “leaves in the air.” One definition “embelezar” which translates as “when something produces in someone such admiration or shock that they momentarily forget all else,” may lead us to the astrological and astronomical term “eclipse” or the verb “to eclipse.” The analogy of the eclipse is “privileged by some subaltern discourses precisely for being an area that is inaccessible, invisible and unknown to the intelligence of power.” After restating and parsing the Neo-Baroque writer Severo Sarduy’s definition of the ellipsis as the baroque retombée of the eclipse, a “longitudinal dilation of the circle that creates two centers, one luminous and one blackened,” Santiago-Díaz paraphrases Sarduy’s argument stating, “As an expression of a new cosmology, the most radical ellipsis of the Neo-Baroque articulates itself as a proliferation of the sign that breaks with the homogeneity of logos and lack as the epistemic foundation of the subject.”6

With Santiago-Díaz in mind, we can think of how the time between the two initial dates—the self-dedication and the dedication—forms an ellipse in which the formative journey follows the telos of the matrilineal list. Animal fiero y tierno rewrites a genealogical narrative by offering a similar but altered matrilineal counter-narrative, yet the womb—the literary figure that structures the book—breaks with the linearity of the suggested genealogy by (dis)placing it’s centered nothingness, leaving it at the end of the lineage, as an unnamed and unnamable subject, still becoming-being. The lineage is the giving birth to lineage. It replaces a patrilineal lineage of heterogeneous passing-ons with a structure whose beginning anticipates a space “ALWAYS”-to-be(-)filled through continual self-displacement.

***

[box]

acercanamente lejos

de esta pequeña historia

expandida hacia todo deteniéndose.

se oye que dicen:

qué importa tu tristeza,

tu alegría,

tu hueco aquel sellado para siempre,

tu pequeño placer,

tus soledades

mira hacia atrás, y mira a todas partes.

yo miro,

de millones de pequeñas historias

está poblado todo:

¿importa si me cólera

detiene una sonrisa?

¿importa si algún rostro

tropieza con mi puño,

si algún oído atento

rueda hasta mi canción imperceptible?

¿qué importará, me digo

cuanta risa futura

fluya de mi placer hacia otra lágrima?

¿importa si mi pena

alegra la bondad de un caminante?

mirándome las uñas

y rebuscando esta pequeña historia

por dentro de mis ojos diminutos

descubro la partícula gigante

donde habito.

closely far

from this small (hi)story

expanded towards everything stopping.

one hears them say:

what does your sadness matter,

your joy,

your hollow that’s sealed forever,

your small pleasure,

your solitudes

i look back, and i look everywhere.

i look,

millions of small (hi)stories

populate everything:

does it matter that the tear

that sometimes accompanies and abandons me

merges with the air?

does it matter that my rage

stops a smile?

does it matter if some face

trips on my fist,

if some attentive ear

rolls towards my imperceptible song?

what will it matter, i say to myself,

how much future laughter

flows from my pleasure toward another tear?

does it matter if my sorrow

brings joy to a traveler’s kindness?

looking at my nails

and searching for that small (hi)story

within my diminutive eyes

i discover the giant particle

i inhabit.

[/box]

[line]

My relationship to my own “womb” is characterized by rejection, but I felt freed by this book, not because I share Dávila’s experiences, but because there is something incredibly queer about choosing one’s lineage backwards, about finding that lineage through poetry rather than patriarchal genealogy. In a way, this dedication was the first example I saw of what I would one day come to call queer family. It has no beginning or ending. We are an ellipse/ellipsis/eclipse.

When did I first read Animal fiero y tierno? My memories tell me I was alone, and when I shared these poems with Lía, with Gaddo, with Polo, we were alone together. Angelía y Gaddiel dicen que fui quien les habló por primera vez sobre Ángela. Angelía juega con su propio nombre/su nombre propio: Angelía Mar Rivera…(Angel)a (Mar)(ía)…declama poemas, relaciones nuevas con el cuerpo, cuerpaza el papel. Gaddo memoriza fragmentos. Me siento por ahí hablando de la tristeza, en el piso de Chardón esperando que escampe. Together we shed all of the things we carried, mayagüezanxs al fin, we shed them slowly, as if tasting ourselves, sinning through some autodedicatoria, some masturbatory gesture exteeeee(ended) into openness. What is pleasure, intimacy and anger without telos, if not poetry, Angela, Anjelamaría?

[box]

notes:

1 Fierce and Tender Animal

2 Gelpí, Juan. Literatura y paternalismo en Puerto Rico. San Juan, P.R.: Editorial De La Universidad De Puerto Rico, 1993. Print.

3 This is the name of Animal fiero y tierno’s first region.

4 Dávila, Anjelamaría. Animal Fiero Y Tierno. Río Piedras: QueAse, 1977. 7. Print.

5 (8)

6 Santiago-Díaz, Eleuterio. Escritura Afropuertorriqueña y Modernidad. Pittsburgh, PA: Inst. Internacional de Literatura Iberoamericana, Universidad De Pittsburgh, 2007. 84. Print. [/box]

[line][line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Screen-Shot-2017-03-24-at-8.27.52-PM-e1490401739906.png[/textwrap_image] Raquel Salas Rivera ha publicado poemas y ensayos en numerosas revistas y antologías. En el 2011, publicó su primer libro, Caneca de anhelos turbios, con Editora Educación Emergente. En el 2016, publicó su segundo libro, oropel/tinsel, con Lark Books & Writing Studio, y su tercer libro huequitos/holies con La Impresora. En el 2017, Ediciones Alayubia publicó su cuarto libro, tierra intermitente. Actualmente es editorx contribuyente para The Wanderer. Si para Roque Dalton no existe revolución sin poesía, para Raquel no existe poesía sin Puerto Rico. Puedes aprender más sobre su trabajo si visitas raquelsalasrivera.com.

Raquel Salas Rivera has published poetry and essays in numerous anthologies and journals. In 2011, their first book, Caneca de anhelos turbios, was published by Editora Educación Emergente. In 2016, their chapbook, oropel/tinsel, was published by Lark Books & Writing Studio, and their chapbook huequitos/holies was published by La Impresora. In 2017, Ediciones Alayubia published their fourth book, tierra intermitente. Currently, they are a Contributing Editor at The Wanderer. If for Roque Dalton there is no revolution without poetry, for Raquel there is no poetry without Puerto Rico. You can find out more about their work at raquelsalasrivera.com.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]