4th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 6 :: AUDEN IN ICELAND :: Andre Bagoo on W.H. Auden

When he was a child, W. H. Auden had a friend. One weekend, when Robert Medley was staying at the Audens’ home at Harborne, England, Auden’s mother found a poem that alarmed her. She gave it to Auden’s father, physician Dr George Auden, who called the boys in to the study and interrogated them about their friendship. There, among the rows of silent books, the boys assured their relationship had never been sexual. Nonetheless, at the age of 15, Auden was deeply in love with Medley. It was at Medley’s suggestion that Auden had begun to write poetry. Dr Auden burned the poem.

When he was a child, W. H. Auden had a friend. One weekend, when Robert Medley was staying at the Audens’ home at Harborne, England, Auden’s mother found a poem that alarmed her. She gave it to Auden’s father, physician Dr George Auden, who called the boys in to the study and interrogated them about their friendship. There, among the rows of silent books, the boys assured their relationship had never been sexual. Nonetheless, at the age of 15, Auden was deeply in love with Medley. It was at Medley’s suggestion that Auden had begun to write poetry. Dr Auden burned the poem.

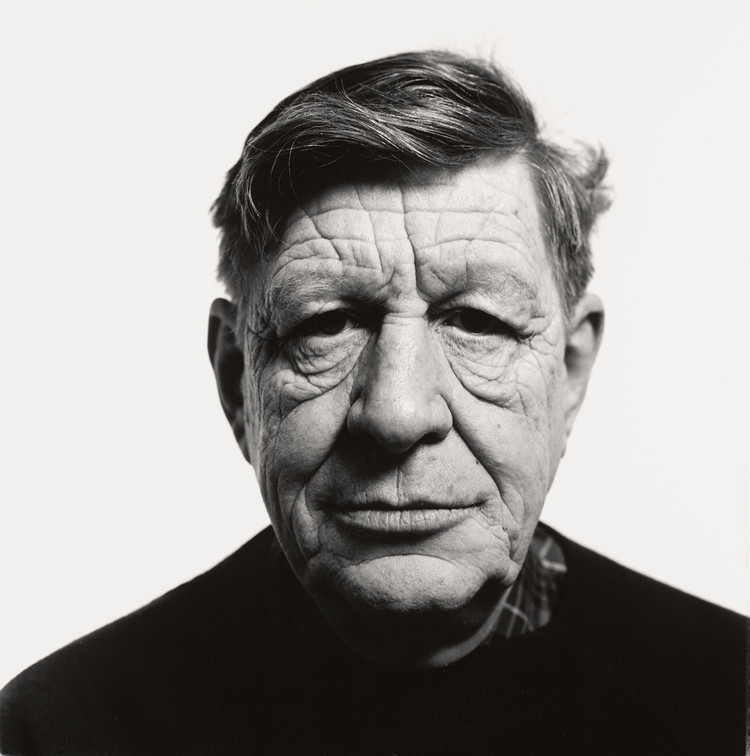

When I think of Auden, I think of his face and the story it tells. All of the photographs agree. In his later years, his wrinkles were unmistakable. He looked like weathered rock. Or a slab of Arctic ice, cracked and hewn by time. I imagine his eyes as black pools, forming fluvial valleys, crying, whether in sorrow or joy. In a sense, Auden’s face tells the story of his first love. And in a sense, all of his poetry tells that story. What was unspeakable in that study at Harborne, is loud and clear now.

When I was writing BURN, I was drawn to Auden’s contradictions. On the one hand, here was a poet concerned primarily with form. He once said poetry should be, “classic, clinical and austere”. There is something of his childhood love for sciences and machines, for geography and rock formations (he wrote a poem called “In Praise of Limestone“) on how he adopted certain forms. Yet it wasn’t all just about the structures. It was also about the images and the feelings. The stonier his writing, the more emotional. Each poem is like a relic fusing molten feeling with hard, inexorable truth. Consider, for example, ‘The Prophets‘:

[box] Perhaps I always knew what they were saying:

Even the early messengers who walked

Into my life from books where they were staying.

Those beautiful machines that never talked

But let the small boy worship and learn

All their long names whose hardness make him proud,

Love was the word they never said aloud

As something that a picture can’t return. [/box]

The form mirrors the objects of the poet’s affection. Just as emotionless machines trigger affection in the small boy, so too the rhyme scheme allows love to become the word that rings loudest. It has been said that no other poet during Auden’s lifetime used the word love as much in his poetry. What else are we to expect of a writer whose entire career and output, in a way, came because of love? Love appears again and again, as it does in, ‘Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone’ – read in the funeral scene of Four Weddings and a Funeral – and, ‘As I Walked Out One Evening‘ which begins:

[box] As I walked out one evening,

Walking down Bristol Street,

The crowds upon the pavement

Were fields of harvest wheat.

And down by the brimming river

I heard a lover sing

Under an arch of the railway: ‘Love has no ending.

‘I’ll love you, dear, I’ll love you

Till China and Africa meet,

And the river jumps over the mountain

And the salmon sing in the street,

‘I’ll love you till the ocean

Is folded and hung up to dry

And the seven stars go squawking

Like geese about the sky.

‘The years shall run like rabbits,

For in my arms I hold

The Flower of the Ages,

And the first love of the world.’ [/box]

There is certainly something of this in my poem, ‘The Night Grew Dark Around Us‘, the opening poem of my first book, Trick Vessels:

[box] Let the daughter of that hibiscus say:

“His love has no end.”

Let the mother of the daughter say:

“His love has no end.”

Let the author of the mother say:

“His love has no end.”

Let the love, which is a flower, say:

“His love had no end.”

Let the flower, which is the night, say:

“His love has no end.” [/box]

As I was writing BURN, I became drawn more and more to the details of Auden’s life, his collection of essays, The Dyer’s Hand, and interviews and documentaries about him. [Ed: read this 1963 review of TDH by John Berryman in the NY Review of Books.] I felt I was getting to know him better. I believe that he always had a burning, unquenched thirst for love, whatever the vagaries of his relationships. Was this a yearning stemming from a theological belief? Or was everything he did in the shadow of those tentative moments at school with Medley? I pictured Auden, the unrequited lover, jilted since 15, wandering aimlessly amid the landscape of Iceland. (Auden worked on a collaboration with Louis Mac Niece, which was published as Letters from Iceland.) I began to imagine the poet in all sorts of contexts, at a bar on the prowl, at home eating ice-cream, in the hospital recovering from illness. In response to his tremendous impact on me, I began to picture a character called Auden and placed him at the centre of a sequence called ‘Auden in Iceland‘. And I made a film-poem about being in love with him, which I am. I’m so glad I met him.

[box] From ‘Auden in Iceland‘

II.

A sheet of paper crumpling on

Vodka, crevices draining into place,

Slopes of mountains torn agape.

I am in love with his face.

Desiccated cracks, diurnal longings –

Hewn, and by blades, eye a valley;

Skaters make grids of icy sweat.

This limestone, I will marry.

Not his soul or his mind

Or anything in his time

Just rain, salt, sub-surface chance.

His crystal face is mine.

V.

Auden planned it precisely:

All his life built to one moment.

He knew the afterlife could come in an instant.

And so he walked with it wherever he went.

For years.

If there was a car accident, or a plane crash, or a sniper attack

He would be ready.

If it met him in a hospital suite,

If it came in his sleep,

He trusted his subconscious to deploy it:

So well done, his body would not forget

The intricate imaginings of his cerement.

He believed one thing:

Each man must create his afterlife,

Must imagine how the light changes, the eyes dilate

And how the world could be.

And when he dies,

It unfolds eternally. [/box]

BURN by Andre Bagoo – a film poem

[line] [line] [textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/10371481_10100386546245626_4102992093905223133_n-e1428336685855.jpg[/textwrap_image]ANDRE BAGOO is a poet and journalist working in Trinidad. His second book of poems, BURN, is published by Shearsman Books.

Editor’s Note: Ordinarily, as a rule, this series attempts to make space for new contributors every year — we see it as a way to grow our community of voices, and reach new audiences — but that’s exactly why we make an exception for Andre Bagoo, whose presence here strengthens and reinforces our ties with the vibrant creative community in Trinidad and Tobago, where he is based. As I wrote in my notes for his first post for us on Poetry and Journalism, for our Field Notes series, our relationship is “one of those ‘why I love the internet’ moments”: a chance reading of Jacob Perkins and Matt Nelson’s 30/30/30 post on Paul Legault, a submission to our second PRINT magazine (then under the Exit Strata umbrella), and then participation in Field Notes, and the 30/30/30 series for now three years running, with tributes to DH Lawrence, Derek Wolcott, and now Auden. He also passed the torch and brought in Vahni Capildeo and Shivanee Ramochlan last year. For even more on poetic happenings in Trinidad and Tobago, check out this piece from their 100,000 Poets for Change organizers, part of our collaborative series with 100TPC some years back.

[line] [h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5] [mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”] [line] [recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]