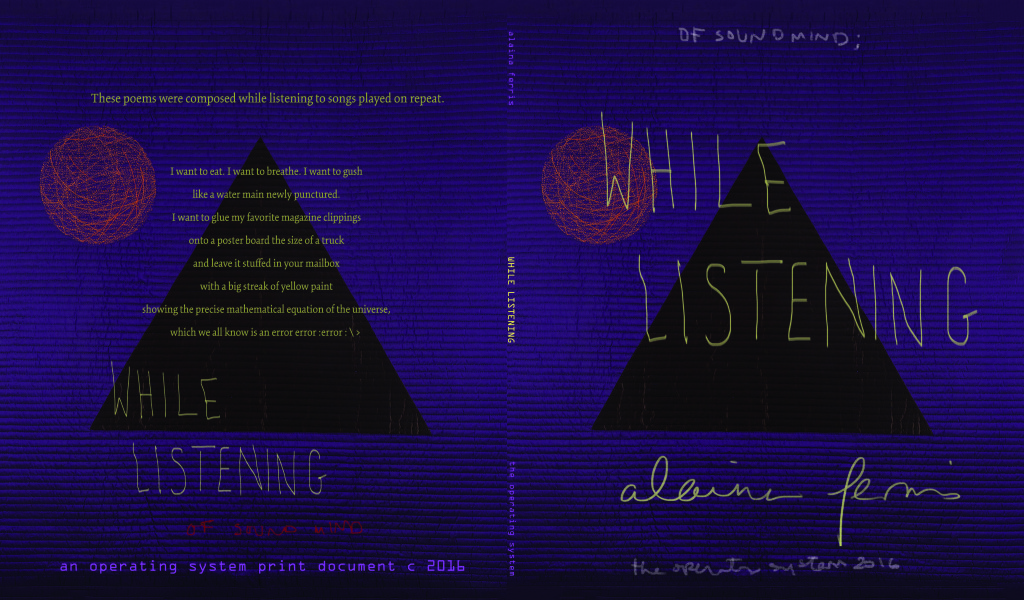

[re:con]versations :: OF SOUND MIND :: process and practice with WHILE LISTENING's Alaina Ferris

[line]

[line]

[box]

[quote] In 2016 The Operating System initiated the project of publishing print documents from musicians and composers, beginning with Everybody’s Automat and this year’s chapbook series, all of which fall under the OF SOUND MIND moniker, and all of which are written by creative practitioners who work in both poetry and music. I asked each of them a series of questions about the balance of these two disciplines in their practice, which I’ll share with you here.

Please consider this template, approaching The OS’s key concerns of personal and professional practice/process analysis combined with questions of social and cultural responsibility, as an Open Source document — questions to ask yourselves or others about process and the role of poetry today.

In this conversation, I talk to Alaina Ferris about her work and debut chapbook on The OS Press, While Listening.

– Series Editor / OS Managing Editor Lynne DeSilva-Johnson [/quote][/box]

[line][line]

[articlequote] An artist does not fulfill a role, but defines it for themselves. My role is certainly different than many of my peers. I use poetry as a keyhole: the world is baffling and beautiful and language is an access point. Poetry, in addition to being my medium, is my coping mechanism. ” – Alaina Ferris [/articlequote]

[line][line]

Who are you?

Why are you a poet / why do you write?

When did you decide you were a poet (and/or: do you feel comfortable calling yourself a poet, what other titles or affiliations do you prefer/feel are more accurate)?

I’m Alaina Ferris. I grew up in Las Vegas, a city that commodifies alternate realities. I grew up skeptical that the world around me was any more or less than the worlds of my own imagining. That invitation to fantasy, along with the city’s pressure of hyper-sexualization, led me to become an introvert at a young age. I found myself writing poetry, playing the piano, and socializing through online text-based RPGs. Those forums are my ways of coping, understanding, and loving the world.

What’s a “poet”, anyway?

What is the role of the poet today?

What do you see as your cultural and social role (in the poetry community and beyond)?

An artist does not fulfill a role, but defines it for themselves. My role is certainly different than many of my peers. I use poetry as a keyhole: the world is baffling and beautiful and language is an access point. Poetry, in addition to being my medium, is my coping mechanism. Meanwhile, there are many amazing poets who are using their art to speak out about issues, politics, and gender identify. Two peers whose work I respect greatly on that front are Christopher Soto and Chase Berggrun.

Talk about the process or instinct to move these poems (or your work in general) as independent entities into a body of work. How and why did this happen? Have you had this intention for a while? What encouraged and/or confounded this (or a book, in general) coming together? Was it a struggle?

The conceit of this book was unified from the start: write a poem start to finish while listening to a song on repeat. I actually wrote two of the first poems (‘For P.K.’, and ‘For T.F.’) as kickstarter rewards for the album of my first band, Small Dream Ada. At that time, I was having trouble writing, so I put on contemporary classical music to help give my hands a sense of motion. Music always opens up my writing because it gives me something to respond to. These poems are ekphrastic, contemplative, and participating with Frank O’Hara’s movement, Personism.

Did you envision this collection as a collection or understand your process as writing specifically around a theme while the poems themselves were being written? How or how not?

Because of their shared technical approach, these poems have a sense of unity. Their sequence can create a narrative, as movements in a symphony, but they are also meant to be single poems.

[line]

Speaking of monikers, what does your title represent? How was it generated? Talk about the way you titled the book, and how your process of naming (poems, sections, etc) influences you and/or colors your work specifically.

My title is very simple: it represents the mode of the work itself. Instead, I’ll talk about how I chose the songs that are the subtitles for each piece. Sometimes, I selected songs that matched the person for whom the poem was written: their personality, energy, or

perhaps a conversation we had about a particular band. For W.B., for Wiley Birkhofer, I found the song ‘3/4 Heart’ in my Spotify inbox a month after Wiley died. Other times, as was the case with ‘Storm’ for R.D., I picked a song which mirrored the energetic structure of the poem.

What does this particular collection of poems represent to you

…as indicative of your method/creative practice?

…as indicative of your history?

…as indicative of your mission/intentions/hopes/plans?

These poems are dedicated to people, but they are ultimately rooted in the first person perspective — me dealing with the frenetic landscape of New York city as a piano teacher, performer, composer, and poet. My work darts from place to place. Frenzied activity is something I both fight and draw inspiration from.

What formal structures or other constrictive practices (if any) do you use in the creation of your work? Have certain teachers or instructive environments, or readings/writings of other creative people (poets or others) informed the way you work/write?

Because I sing and play piano, I am very much influenced by the lyric and the internal rhyme. I don’t always care to follow strict meter, but can easily slip into it. When writing, I am often speaking my work out loud. This allegiance to sonic quality is something I learned from working with Eleni Sikelianos and Anne Waldman, both incredible orators.

Talk about the specific headspace of being a musician / composer / performer – when and how do you feel you enter a space of consciousness in which “sound” or “music” is the dominant sense?

Being a musician and composer alters the way I write because the melody of a poem (this is Ezra Pound’s term: melopoeia) comes first. Image is next (phanopoeia), then logic (logopoeia). Sound by itself can evoke emotion, this is something I feel viscerally when listening to a choir in a boomy room. If a poem can summon emotion through sound alone, then it provides the opportunity for meaning and narrative.

Do you feel that you are ever unaware of sound? (How) does your relationship to sound/music inform and/or affect and/or change other parts of your life / day / experience?

[articlequote]I love it when the screech of two subway cars creates a harmony, just like I love it when my dog howls to match the pitch of a passing ambulance, or when the car wheels whir enough that I can sing over their drone. [/articlequote]

Music impacts my life on a financial level, because teaching music lessons is how I sustain myself in NYC, and impacts how I perceive sound as a pedestrian. I do think, like most musicians, I am very sensitive to frequencies.

[line]

Do you consider yourself equally musician/composer/poet? Are there other equally important disciplines, influences, labels or other words you’d want to call our attention to that we might not know that you feel are important in understanding your creative practice?

If we didn’t get asked “what do you do” and force ourselves to fit into easily consumable disciplinary categories, what would you like your title to be, if anything?

Maureen McLane, William Wordsworth, and video games have all instilled in me an irremovable desire to become a troubadour. I love Josquin Des Prez, the 15th century Franco Flemish composer. I especially adore his choral writing (which has very much influenced my own writing).

Describe in more detail the relationship between music and language in your life and practice. How and when are these discrete influences / practices and how/when are they interconnected? How do they influence each other? Do they ever not?

After teaching 4-5 hours of a piano and voice lessons on weekdays, in addition to my own composing and practicing in the morning, I often end the day by chopping a clove of garlic in silence.

In terms of your written or text based work, do you “hear” it, speak it out, hear its rhythms, before you write or as you write and/or before you perform? Do you ever memorize your texts / treat them more like a score or sheet music?

I do memorize my texts, especially those that have a more defined meter. I also occasionally set poems to music.

Let’s talk a little bit about the role of poetics and creative community in social activism, in particular in what I call “Civil Rights 2.0,” which has remained immediately present all around us in the time leading up to this series’ publication. I’d be curious to hear some thoughts on the challenges we face in speaking and publishing across lines of race, age, privilege, social/cultural background, and sexuality within the community, vs. the dangers of remaining and producing in isolated “silos.”

It is easy to fall into the safety of what one knows. I grew up reading white, male poets because those were the books put into my hand. And I loved and still love them. I spent hours and hours reading and memorizing. That said, I believe it is a social responsibility for any artist to look beyond themselves and challenge their own upbringing, wherever it is that they might be coming from, to understand what is giving momentum to other artists and why.

[line]

[box]

Alaina Ferris is a poet, composer, and performer. She received a B.A. in Music and English from the University of Denver and an M.F.A. in Poetry from New York University. Alaina lives in Brooklyn where she teaches piano lessons.

[/box]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]