POETRY MONTH 30/30/30 : Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 23: Lauren Marie Cappello on Lorine Niedecker

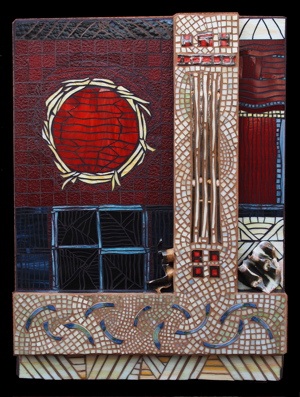

The way it happens with water is like this: The beginning is unclear, maybe it happened first with rain, maybe the clouds made water from vapor or notes on dreams. Also, there is the way the water moves; it is sure of itself, searching the lowest point - steady in the breaking down of it retaining its structure to the smallest division. It asserts itself in seeking to fill its surroundings, tracing a path from one substance to the next leaving great distinction between where it is and where it is not. Lorine Niedecker’s poetry contains the essence of the water she lived by, moving across one phenomenon, seeking another in connection like a river, leaving a trail on the small portion of those places her poetry touches.

The way it happens with water is like this: The beginning is unclear, maybe it happened first with rain, maybe the clouds made water from vapor or notes on dreams. Also, there is the way the water moves; it is sure of itself, searching the lowest point - steady in the breaking down of it retaining its structure to the smallest division. It asserts itself in seeking to fill its surroundings, tracing a path from one substance to the next leaving great distinction between where it is and where it is not. Lorine Niedecker’s poetry contains the essence of the water she lived by, moving across one phenomenon, seeking another in connection like a river, leaving a trail on the small portion of those places her poetry touches.

Niedecker's work places the objects before the reader; it is in the selection of them by this poet that the scene is imbued with meaning. All else is relative. Throughout the objectivist movement, most avoided metaphor in their poetry. They took to the style of portraying the happening as it was with a feeling that in its conveyance to the audience the intended emotion would be transmitted. Niedecker’s work is a hybrid of objectivism blended with her interest in surrealism, which was contained and bubbling just below the surface. In a letter to Monroe in 1934, Lorine wrote"…the whole written with the idea of readers finding sequence for themselves, finding their own meaning whatever that may be, as spectators before abstract painting."

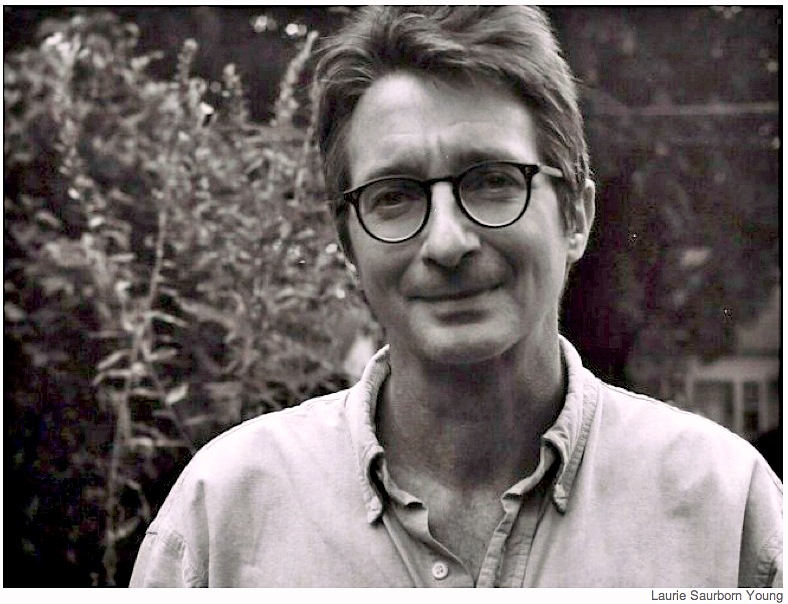

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 22 :: Tony Hoffman on Vicente Huidobro

I don’t recall where I first encountered the works of Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro (1893-1948)—most likely in the introduction to a collection by one of his contemporaries who came to overshadow him (Neruda or Borges). In America, at least among English-speaking poets, his work is largely forgotten; I don’t remember his name ever coming up in a conversation I didn’t initiate. But he is still well loved by people with an interest in Spanish-language poetry.

A century ago, he initiated a literary movement known as Creationism (no relation to the term’s current religious context), which holds that a poem is something new, created by the author for its own sake, not to act as commentary or to please either author or audience. He wrote of the created poem, “Nothing in the external world resembles it; it makes real what does not exist, that is to say, it turns itself into reality. It creates the wonderful and gives it a life of its own. It creates extraordinary situations that can never exist in the objective world, that they will have to exist in the poem so that they exist somewhere.”

I don’t recall where I first encountered the works of Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro (1893-1948)—most likely in the introduction to a collection by one of his contemporaries who came to overshadow him (Neruda or Borges). In America, at least among English-speaking poets, his work is largely forgotten; I don’t remember his name ever coming up in a conversation I didn’t initiate. But he is still well loved by people with an interest in Spanish-language poetry.

A century ago, he initiated a literary movement known as Creationism (no relation to the term’s current religious context), which holds that a poem is something new, created by the author for its own sake, not to act as commentary or to please either author or audience. He wrote of the created poem, “Nothing in the external world resembles it; it makes real what does not exist, that is to say, it turns itself into reality. It creates the wonderful and gives it a life of its own. It creates extraordinary situations that can never exist in the objective world, that they will have to exist in the poem so that they exist somewhere.”

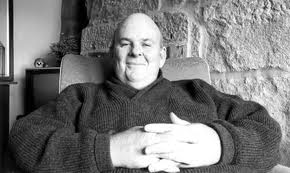

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 21:: David King on Frederick Seidel

On Frederick Seidel

People often ask me what I’m reading, who I’m reading, who I like. My answer is always the same. I say nothing. I say nothing to protect them. I say nothing, like a hero. The problem I find is that the people who ask me what I’m reading, who I’m reading and who I like aren’t at rock bottom. They aren’t in dire need of an artistic overhaul. They aren’t where I was when I first experienced Frederick Seidel’s Ooga-Booga. They’re just asking, often, to be polite, which is the worst kind of asking.

In August of 2009, everything was going wrong. The creative world in which I

was consumed was turning indie. Vegan. It was going soft, because to walk around with a hard-on in one’s head was impolite. The world around me was craving sterility. Political correctness of the mind and body was becoming impotent-making. I was growing sleepless with softness. I started to feel like the world was slowly denying my human right to tear. PC thought police had waged war inside my head with Nerf truncheons.

What I found in Ooga-Booga was a harsh reality of the mind. I found an

honest viciousness. I found humor in the utterly terrifying. I found terror in the utterly humorous. I found that I was terrified to find certain things funny. I found that my body would force a laugh to conceal a multitude of other emotions. But most importantly, I found that all of this could be done with poetry.

On Frederick Seidel

People often ask me what I’m reading, who I’m reading, who I like. My answer is always the same. I say nothing. I say nothing to protect them. I say nothing, like a hero. The problem I find is that the people who ask me what I’m reading, who I’m reading and who I like aren’t at rock bottom. They aren’t in dire need of an artistic overhaul. They aren’t where I was when I first experienced Frederick Seidel’s Ooga-Booga. They’re just asking, often, to be polite, which is the worst kind of asking.

In August of 2009, everything was going wrong. The creative world in which I

was consumed was turning indie. Vegan. It was going soft, because to walk around with a hard-on in one’s head was impolite. The world around me was craving sterility. Political correctness of the mind and body was becoming impotent-making. I was growing sleepless with softness. I started to feel like the world was slowly denying my human right to tear. PC thought police had waged war inside my head with Nerf truncheons.

What I found in Ooga-Booga was a harsh reality of the mind. I found an

honest viciousness. I found humor in the utterly terrifying. I found terror in the utterly humorous. I found that I was terrified to find certain things funny. I found that my body would force a laugh to conceal a multitude of other emotions. But most importantly, I found that all of this could be done with poetry.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 20:: Annaliese Downey on CA Conrad

CA Conrad gave a reading at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where I study poetry, about a week ago, and afterwards the general consensus among the students in attendance was that Conrad was “insane.” We meant this affectionately and admiringly. If the motto of the Situationists, with whom Conrad has much in common, was “Be realistic—demand the impossible!”, then a suggested motto for those wishing to proceed in the spirit of Conrad might be, “Be reasonable—do what is insane!”

Conrad’s most recent book of poems, A Beautiful Marsupial Afternoon, [from Wave Books] is a guide to practical insanity. Collected within are twenty-seven “(soma)tic exercises,” instructions for the radical disruption of routine living at the individual level, and the poems resulting from those created conditions. For example: “(Soma)tic 7: Feast of the Seven Colors,” which instructs the reader to consume and surround themselves with a single particular color each day for seven days. Or “(Soma)tic 17: OIL THIS WAR!,” an exercise in making visible the linkages between waste and war. Many of the exercises are even wilder, weirder, and more uncomfortable than these, and Conrad has performed them all.

CA Conrad gave a reading at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where I study poetry, about a week ago, and afterwards the general consensus among the students in attendance was that Conrad was “insane.” We meant this affectionately and admiringly. If the motto of the Situationists, with whom Conrad has much in common, was “Be realistic—demand the impossible!”, then a suggested motto for those wishing to proceed in the spirit of Conrad might be, “Be reasonable—do what is insane!”

Conrad’s most recent book of poems, A Beautiful Marsupial Afternoon, [from Wave Books] is a guide to practical insanity. Collected within are twenty-seven “(soma)tic exercises,” instructions for the radical disruption of routine living at the individual level, and the poems resulting from those created conditions. For example: “(Soma)tic 7: Feast of the Seven Colors,” which instructs the reader to consume and surround themselves with a single particular color each day for seven days. Or “(Soma)tic 17: OIL THIS WAR!,” an exercise in making visible the linkages between waste and war. Many of the exercises are even wilder, weirder, and more uncomfortable than these, and Conrad has performed them all.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 19 :: Jack Cooper on Hala Alyan

The Faces of Influence - John Jack Jackie (Edward) Cooper Faces or facets? Am I being facetious in considering fact a species of essence, even essences, precipitate—from the lot conjoined—a chemical residue, like water, plain oxygen: and if residue what of, why not, feces? Fax—is this, are they—iteration of facsimile? Effect, then, whether spelled—particularized—with e or a, Classical byproduct: aeffect,a lode of Pindarian award for aesthetic gain or distinction. I first saw—first beheld—Hala Alyan in the dark. She half sat, upright in the darkness familiar from unknown places. No pitch, the tentative sensual isolation adheres to bodies, but another vividly sensuous through which perception nears to the material: where Eros does prevail—palatial imagining, short-lived, with Psyche. Thanks, if such issue exist, conceded apology, acknowledgment, ripening gratitude flow from the misunderstanding, sundered conjunction, memory, recall, facsimile, fable (weakness of memory at maximum componential strength), influence.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 18:: Ben Wiessner on Dean Young

Before Fall Higher’s table of contents Dean Young booms out a call to action:

hark, dumbass,

the error is not to fall

but to fall from no height

As soon as I came across those lines I snapped a grainy picture on my prehistoric flip-phone and sent them to the person who knows most clearly my errors, how much of that dumbass I can be.

This book belonged in my apartment. It was meant to be poured over on a couch, read with dinner. His words and I line-danced toward and from each other, catching promising glimpses between partner switches:

When you finally admit you’re broken,

Can I come back up now? asks the chair

with its leg snapped in the basement

and Don’t even get me started, says the sky.

- (“Irrevocable Ode”)

Before Fall Higher’s table of contents Dean Young booms out a call to action:

hark, dumbass,

the error is not to fall

but to fall from no height

As soon as I came across those lines I snapped a grainy picture on my prehistoric flip-phone and sent them to the person who knows most clearly my errors, how much of that dumbass I can be.

This book belonged in my apartment. It was meant to be poured over on a couch, read with dinner. His words and I line-danced toward and from each other, catching promising glimpses between partner switches:

When you finally admit you’re broken,

Can I come back up now? asks the chair

with its leg snapped in the basement

and Don’t even get me started, says the sky.

- (“Irrevocable Ode”)

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 17:: Jim Lounsbury on Les Murray

POETRY : A DREAM SEA OF WORDS by Jim Lounsbury

About ten years ago, I stumbled into a heated debate with a filmmaker friend about whether words or imagery was a more effective way to convey emotion. I argued the case for words, and he took the side of imagery. As the disagreement escalated to a passionate squabble and then to a stamp your feet and beat on your chest free-for-all, I began to wonder what gave me such a strong opinion on the issue. We were both filmmakers. We were both avid photographers. We were both working in the visual arts. What then, was my problem with accepting the visual medium as the superior art form? At the end of the night, we agreed to disagree, and I left, still confused about why I was so confident in the power of words.

Of course, my affinity for words could be biological. My internal chemistry set might not react to imagery as powerfully as it does to a well placed noun, but I wasn't going to let myself off the hook that easily. Over the course of many months, my thoughts often returned to this argument until a plausible explanation finally struck me a few weeks later. Imagery was powerful at evoking emotion, but words have the ability to surgically cut to the bone and identify a precise emotion.

POETRY : A DREAM SEA OF WORDS by Jim Lounsbury

About ten years ago, I stumbled into a heated debate with a filmmaker friend about whether words or imagery was a more effective way to convey emotion. I argued the case for words, and he took the side of imagery. As the disagreement escalated to a passionate squabble and then to a stamp your feet and beat on your chest free-for-all, I began to wonder what gave me such a strong opinion on the issue. We were both filmmakers. We were both avid photographers. We were both working in the visual arts. What then, was my problem with accepting the visual medium as the superior art form? At the end of the night, we agreed to disagree, and I left, still confused about why I was so confident in the power of words.

Of course, my affinity for words could be biological. My internal chemistry set might not react to imagery as powerfully as it does to a well placed noun, but I wasn't going to let myself off the hook that easily. Over the course of many months, my thoughts often returned to this argument until a plausible explanation finally struck me a few weeks later. Imagery was powerful at evoking emotion, but words have the ability to surgically cut to the bone and identify a precise emotion.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 16:: Karen Clark on Marilyn Nelson

I want to talk about the work of Marilyn Nelson, whose poems fill me with the same mixture of awe, reverence and exultation that I experienced last month standing in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in front of the Van Gogh exhibition. It is the sense of privilege at having witnessed this miracle: that it is possible to take suffering, pain, and man’s brutal inhumanity to man and transform them, through the alchemy of art and genius, into works of sheer glory that become a lifelong blessing to the beholder, comforting us with the knowledge that the pain and the suffering were not wasted, not meaningless, for this beautiful work of art came out of it all, to spread its balm upon the human spirit and remind us that the artist’s sacred mission is to heal the world. Only recently I was overjoyed to see that Nelson (who has been honored many times for her work) was the 2011 recipient of the Poetry Society of America’s highest honor, the Frost Medal.

I want to talk about the work of Marilyn Nelson, whose poems fill me with the same mixture of awe, reverence and exultation that I experienced last month standing in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in front of the Van Gogh exhibition. It is the sense of privilege at having witnessed this miracle: that it is possible to take suffering, pain, and man’s brutal inhumanity to man and transform them, through the alchemy of art and genius, into works of sheer glory that become a lifelong blessing to the beholder, comforting us with the knowledge that the pain and the suffering were not wasted, not meaningless, for this beautiful work of art came out of it all, to spread its balm upon the human spirit and remind us that the artist’s sacred mission is to heal the world. Only recently I was overjoyed to see that Nelson (who has been honored many times for her work) was the 2011 recipient of the Poetry Society of America’s highest honor, the Frost Medal.

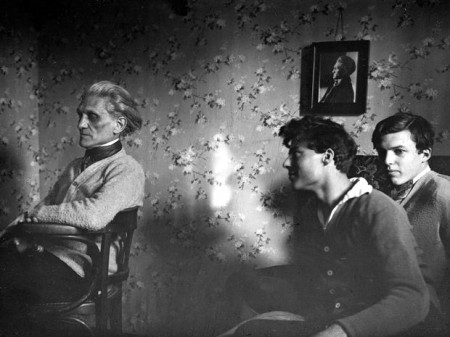

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 15 :: Peter Milne Greiner on Stefan George

The most recent and significant reference to Stefan George’s legacy is Fassbinder’s Satan’s Brew, which is one way of saying there is no legacy that does not involve excavation. Two other ways of hearing about him are through Mallarmé’s biography and exhaustive research of the NAZI party. I can scarcely imagine a more dubious constellation of access points.

George was one of those yesteryear poets who doubled as a public figure. An early conscript of French and German Symbolism, George toiled to shape his reputation not only as a poet, but as the editor of the recherché Blätter Für Die Kunst, and as the oracle of a new German cultural revival. By the turn of the twentieth century, his retinue of young male acolytes in tow, he was poised to affect national transformation. Using poetry.

The most recent and significant reference to Stefan George’s legacy is Fassbinder’s Satan’s Brew, which is one way of saying there is no legacy that does not involve excavation. Two other ways of hearing about him are through Mallarmé’s biography and exhaustive research of the NAZI party. I can scarcely imagine a more dubious constellation of access points.

George was one of those yesteryear poets who doubled as a public figure. An early conscript of French and German Symbolism, George toiled to shape his reputation not only as a poet, but as the editor of the recherché Blätter Für Die Kunst, and as the oracle of a new German cultural revival. By the turn of the twentieth century, his retinue of young male acolytes in tow, he was poised to affect national transformation. Using poetry.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 14 :: Daniel Owen on Bill Kushner

I first encountered Bill Kushner’s work at a reading at the Poetry Project a few years ago. That night, he read from In Sunsetland With You, a book of poems that emanate from young Billy’s relationship with old Abe Lincoln, poems that, with a language of grace and humor, narrate the misadventures of a lonely, horny, eternally innocent, old, sad, and joyous spirit through the wars, highway-watching nights, and skinny-dippings of Sunsetland. What struck me most about these poems, and what continues to strike me through all of Bill's work, is the delicate balance between wrenching and buoying the heart. Bill’s poems are like walking through the world with one’s eyes open, with the workaday bullshit stripped away; he reads the raw Whitman writ on every street corner or fragment of memory, real or imagined.

Over the course of eight books, Bill has rambled through the streets of Sunsetland and New York, across sonnets and daily diary poems, lustily crusing through time present and past, Billie Holiday records, beefcake babies, always in a mood of love, love, love. Yes, love appears on almost every page and it sure feels real, flapping in the face and the mind and the blood of a humble human life.

I first encountered Bill Kushner’s work at a reading at the Poetry Project a few years ago. That night, he read from In Sunsetland With You, a book of poems that emanate from young Billy’s relationship with old Abe Lincoln, poems that, with a language of grace and humor, narrate the misadventures of a lonely, horny, eternally innocent, old, sad, and joyous spirit through the wars, highway-watching nights, and skinny-dippings of Sunsetland. What struck me most about these poems, and what continues to strike me through all of Bill's work, is the delicate balance between wrenching and buoying the heart. Bill’s poems are like walking through the world with one’s eyes open, with the workaday bullshit stripped away; he reads the raw Whitman writ on every street corner or fragment of memory, real or imagined.

Over the course of eight books, Bill has rambled through the streets of Sunsetland and New York, across sonnets and daily diary poems, lustily crusing through time present and past, Billie Holiday records, beefcake babies, always in a mood of love, love, love. Yes, love appears on almost every page and it sure feels real, flapping in the face and the mind and the blood of a humble human life.