2nd ANNUAL NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: DAY 4 :: FARZANA MARIE ON MIKHAIL, CARPENTER, AZZIZADA and POETRY IN SOCIAL CONFLICT

How does poetry grapple with the conflicts and social issues of our time? What can a poem do in the face of rocket-thuds, choking smoke, a child’s pink sandal in a blood-pool on the street? Can it find meaning in

2nd ANNUAL NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: DAY 3 :: RYAN NOWLIN on NORMA COLE

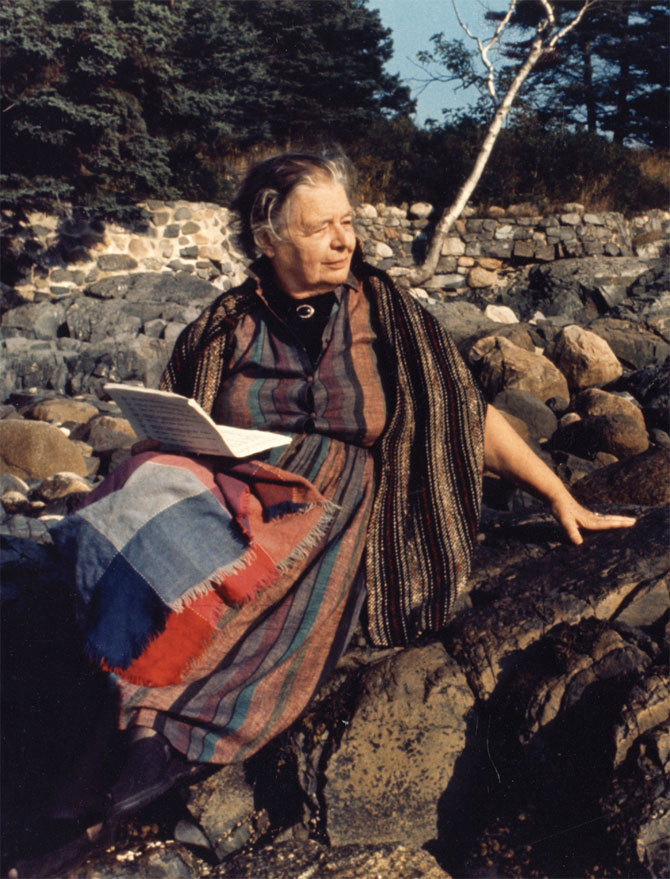

Norma Cole, an experimental poet and visual artist who has lived in the Bay Area since 1977, has received great acclaim for, as she puts it, her “openness to traditions and practices, artists and writings, radically divergent from her own.”

2nd ANNUAL NAPOMO 30/30/30 : DAY 2 :: Gary Sloboda on Buck Downs

Sifting the Workflow: A Comment On The Poetry of Buck Downs Buck Downs is a Washington D.C. poet whose work I’ve been reading for years. Downs’ poetry arrives, old school, on postcards in my mailbox on a monthly basis. As a

2nd Annual 30/30/30 Poetry Month Series :: Inspiration, Community, Tradition :: Day 1 :: Overview / Editor Lynne DeSilva-Johnson on Noah Eli Gordon and Anis Mojgani

The fisherman from Anis Mojgani on Vimeo. HOOOOOOOWOW! Poetry month is upon us once more, and do we ever have a line up for you this year! Last year we initiated a series that generated such an outpouring of goodwill and gratitude

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 30! (Could it be?) :: Lindsey Boldt on Aimé Césaire

The other night poets Julian Brolaski and E. Tracy Grinnell were in town and in a bar rotten with poets in North beach, we got to talking about translation and our varying positions on the desire vs. intimidation spectrum in relation to doing our own translations. I brought up the Martinican poet, Aimé Césaire, as an example of a poet whose writing would interest me enough to translate it. I had been saying how French can feel too precise, too clean, too “le mot juste” when I really love a hot mess. Aimé Césaire takes French, a very coy language, very good at hiding its skeletons, and busts open the closets letting the nasty flesh-dripping zombies come out...and muck things up. Césaire’s French, one that excretes vivacity, vitriol and jouissance like the flora and fauna, the active volcanoes he invokes in his poems, reminds us of the proliferation of Frenches, just like our current proliferation of Englishes, that exist in spite of and because of France’s imperialist history.

Julian brought up the hybridity of Cesaire’s texts, specifically thinking of his “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” [Notebook of a return to the native land] which reminded me of my first encounters with Césaire in college. I had never seen prose live and move like his--be that “free”. I had been trying to wake my own prose writing from a death-like stupor when a professor of French and Francophone literature, Maryanne Bailey, who had visited Césaire in Martinique, introduced us to his collected poetry, translated by Clayton Eshleman. We read it both in French and English and I learned in the process that if you want your writing to live on the page it really helps if you hate the language, hate its restrictions and biases. You have to be willing to beat it up and knock it around a bit. You have to let your true ambivalence show. No, more than that, you have to make the language speak your radical visions; the same ones that would tear apart and rip out at the roots the society that grew that language and the shit storm you grew up in. As Césaire says in his essay “The Responsibility of the Artist” when referring to decolonization,“What is necessary is to destroy it, that is, tear out its roots. This is why true decolonization will either be revolutionary or will not exist.” [ed: full text at link]

The other night poets Julian Brolaski and E. Tracy Grinnell were in town and in a bar rotten with poets in North beach, we got to talking about translation and our varying positions on the desire vs. intimidation spectrum in relation to doing our own translations. I brought up the Martinican poet, Aimé Césaire, as an example of a poet whose writing would interest me enough to translate it. I had been saying how French can feel too precise, too clean, too “le mot juste” when I really love a hot mess. Aimé Césaire takes French, a very coy language, very good at hiding its skeletons, and busts open the closets letting the nasty flesh-dripping zombies come out...and muck things up. Césaire’s French, one that excretes vivacity, vitriol and jouissance like the flora and fauna, the active volcanoes he invokes in his poems, reminds us of the proliferation of Frenches, just like our current proliferation of Englishes, that exist in spite of and because of France’s imperialist history.

Julian brought up the hybridity of Cesaire’s texts, specifically thinking of his “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” [Notebook of a return to the native land] which reminded me of my first encounters with Césaire in college. I had never seen prose live and move like his--be that “free”. I had been trying to wake my own prose writing from a death-like stupor when a professor of French and Francophone literature, Maryanne Bailey, who had visited Césaire in Martinique, introduced us to his collected poetry, translated by Clayton Eshleman. We read it both in French and English and I learned in the process that if you want your writing to live on the page it really helps if you hate the language, hate its restrictions and biases. You have to be willing to beat it up and knock it around a bit. You have to let your true ambivalence show. No, more than that, you have to make the language speak your radical visions; the same ones that would tear apart and rip out at the roots the society that grew that language and the shit storm you grew up in. As Césaire says in his essay “The Responsibility of the Artist” when referring to decolonization,“What is necessary is to destroy it, that is, tear out its roots. This is why true decolonization will either be revolutionary or will not exist.” [ed: full text at link]

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 29 :: Doug Van Gundy on Eamon Grennan

The thing that first drew me to the poetry of Eamon Grennan was his deft handling of ekphrasis and his strong, playful sense of the music that is possible within a poem. “In The National Gallery, London” from his first book, What Light There Is still stands as perhaps the most shining exemplar of these twin traits in his work.

On my first trip to London a few years ago, I carried a photocopy of this poem with me. During my visit to the Dutch galleries that inspired Grennan, I found myself reading the poem out loud to the Rembrandts and Vermeers and Avercamps (and the handful of other patrons within earshot) in an effort to reverse-engineer the impulse that led to this chewy, musical poem.

The thing that first drew me to the poetry of Eamon Grennan was his deft handling of ekphrasis and his strong, playful sense of the music that is possible within a poem. “In The National Gallery, London” from his first book, What Light There Is still stands as perhaps the most shining exemplar of these twin traits in his work.

On my first trip to London a few years ago, I carried a photocopy of this poem with me. During my visit to the Dutch galleries that inspired Grennan, I found myself reading the poem out loud to the Rembrandts and Vermeers and Avercamps (and the handful of other patrons within earshot) in an effort to reverse-engineer the impulse that led to this chewy, musical poem.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 28 :: Roxanne Hoffman on Urayoán Noel

As an active participant of the New York poetry scene since about 2004, as a writer, performer, frequenter of open mics, writing workshop participant, reading series host and small press publisher, I like to think of myself and the other familiar faces on the local poetry circuit as a movement, a not so quiet conspiratorial insurgency, the proverbial flea buzzing in the ear of the silent sleepy majority.

As an active participant of the New York poetry scene since about 2004, as a writer, performer, frequenter of open mics, writing workshop participant, reading series host and small press publisher, I like to think of myself and the other familiar faces on the local poetry circuit as a movement, a not so quiet conspiratorial insurgency, the proverbial flea buzzing in the ear of the silent sleepy majority.

We are the defenders of free speech, free expression, freedom of the press, the right of the individual, and the power of minority opinion. Influence is what we do. We aim to move not only hearts and provoke minds with our little rants but to wake the sleepers to action. While we may make these wake-up calls with charm and style and great humor we never forget for one second it’s all about conveying that subliminal message. What’s the message? Maybe it’s just that we count simply because all human beings can create something of value and interest with a little observation, a little introspection , a little craft, the gift of vocal chords, a pen and a notebook and not much else (though many of us now write on laptops and iPads, even reading off them on the circuit.)

One of my favorite co-conspirators is Nuyorican poet Urayoán Noel. Author of three poetry collections -- Hi-Density Politics(BlazeVOX, 2010), Boringkén (Ediciones Callejón/La Tertulia, 2008), and Kool Logic/La lógica kool (Bilingual Press, 2005); Assistant Professor of English at SUNY; a Bronx Council on the Arts fellow in poetry, as well as a Ford Foundation postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, he has firmly established his foothold in the mainstream, and continues to facilitate the message. His latest project is a book-length study of Nuyorican poetry and its performance from the 1960s to the present. Not only is he making the wake-up call, he is documenting it, never forgetting he is part of a movement.POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 27 :: Annie Paradis on Prageeta Sharma

"The heritage of being alone is to transmit truth to yourself faithfully, to still the paradigm of what opposes you in the world." - ON LOVE, from Bliss to Fill

What if you have daily access to technology, but you want to be in nature, but you want to have a web presence, but you want to find truth, but you yell at your mom, but you try to meditate, but you have an active Netflix account, but you want to be THE PUREST PERSON EVER, but then you are just a human being? Yeah, me too. That's where Prageeta Sharma comes in.

I recently encountered Sharma's Bliss To Fill (Subpress Collective, 2000) a work that actively reminds one of what it is to be a person participating in her own life, but also participating in the world; a person that lives, but checks herself to see how her daily actions expand, how very threadlike it all is as they extend outward into a bigger picture.

"The heritage of being alone is to transmit truth to yourself faithfully, to still the paradigm of what opposes you in the world." - ON LOVE, from Bliss to Fill

What if you have daily access to technology, but you want to be in nature, but you want to have a web presence, but you want to find truth, but you yell at your mom, but you try to meditate, but you have an active Netflix account, but you want to be THE PUREST PERSON EVER, but then you are just a human being? Yeah, me too. That's where Prageeta Sharma comes in.

I recently encountered Sharma's Bliss To Fill (Subpress Collective, 2000) a work that actively reminds one of what it is to be a person participating in her own life, but also participating in the world; a person that lives, but checks herself to see how her daily actions expand, how very threadlike it all is as they extend outward into a bigger picture.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 26 :: Keetje Kuipers on Poets' First Books

This fall I’ll be teaching a class on first collections of poems. We’ll be talking about theme and shapeliness, the individual poems themselves as well as the way they come together to make a collection. I’m interested in first collections because I just published my own first book of poems two years ago, Beautiful in the Mouth, and I’m at work now on a second collection. Working on the second collection has made me reflect on the first book in ways that I hadn’t expected: I question the first book, and try to come up with the reasons for the way I put it together though those reasons have dissolved over time. And thinking about that first book has made me do what I probably should have done before I published it—it’s made me read lots and lots of other poets’ first books, looking in particular for the reasons that they are shaped the way they are. It’s been a wonderful journey, discovering books I hadn’t read before, and revisiting books that I had read and loved without realizing that they were a poet’s first effort. And along the way I think I’ve discovered a thing or two about first books: though they are not always the poet’s best work (and sometimes they are, which is obviously pretty sad in the long run), they are generally the poet’s most raw work, and that hunger and greed and ferocious devouring of language and emotion that happens in those first poems is a pleasure to encounter every time. First books aren’t perfect books, but they are wild ones that don’t hold back. So I’ve been spending the last few days pouring over my books of poetry, looking for first collections that I love, and there are quite a lot to choose from. In fact, I’m having trouble taking my list of thirty books and paring it down to a very reasonable ten (I’m sure that many of us would love to spend our days reading poetry, but my undergraduate students might stop coming to class if I made them read thirty books). However, I’ve got three books that I know will make the final cut, and I’d like to share a poem from each with you today.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 25 :: Ana Bozicevic on Marguerite Yourcenar

disclaimer, from Ana: "if you need a word about why I am featuring a novelist as a poetic influence; her work is poetic to the point of absurdity." et alors...

---

I, YOUrcenar.

None of my friends seem to give a shit about Marguerite Yourcenar. Sure, someone’s father read her in the 80s—probably Memoirs of Hadrian—and there was an interview in the Paris Review with her just then—just at her death. Naming her as an influence has been taken at times (dans mon cas) as an affectation. {This is supposed to be personal, so I’m making it so. But what isn’t? There’s no person, so person’s everywhere.} So this is what I can tell you about Marguerite Yourcenar & “I” (“L’être que j’appelle moi”/the person I call myself, as she puts it):

That

- it was my father who introduced me to her. And started me toward owning most of her books.

- “I” passed her novella of incestuous love, Anna Soror, around my Croatian high school like the mind-porn that it sure was.

- “I” translated parts of her Fires, a reimagining of antique myths—especially the one about Sappho—and made an offering of them to a young woman. This was my idea of courtship; should’ve read Plato’s Lysis first.

- when “I” had a blog for four years, called Quoi? L’Eternité. it was named thus after Yourcenar’s memoirs, not Rimbaud. She also introduced me to Yukio Mishima.

That’s enough now. But from a current vantage, it’s incredibly ironic that Yourcenar’s writing should have served as a queer f-to-f offering – considering the fact that though she quite likely was queer, she was also very oblique about it – what I’ve heard called “old school.” Here’s a passage from that Paris Review interview cited here without value judgment – neither for Yourcenar nor her interviewer and his “deviance:”

disclaimer, from Ana: "if you need a word about why I am featuring a novelist as a poetic influence; her work is poetic to the point of absurdity." et alors...

---

I, YOUrcenar.

None of my friends seem to give a shit about Marguerite Yourcenar. Sure, someone’s father read her in the 80s—probably Memoirs of Hadrian—and there was an interview in the Paris Review with her just then—just at her death. Naming her as an influence has been taken at times (dans mon cas) as an affectation. {This is supposed to be personal, so I’m making it so. But what isn’t? There’s no person, so person’s everywhere.} So this is what I can tell you about Marguerite Yourcenar & “I” (“L’être que j’appelle moi”/the person I call myself, as she puts it):

That

- it was my father who introduced me to her. And started me toward owning most of her books.

- “I” passed her novella of incestuous love, Anna Soror, around my Croatian high school like the mind-porn that it sure was.

- “I” translated parts of her Fires, a reimagining of antique myths—especially the one about Sappho—and made an offering of them to a young woman. This was my idea of courtship; should’ve read Plato’s Lysis first.

- when “I” had a blog for four years, called Quoi? L’Eternité. it was named thus after Yourcenar’s memoirs, not Rimbaud. She also introduced me to Yukio Mishima.

That’s enough now. But from a current vantage, it’s incredibly ironic that Yourcenar’s writing should have served as a queer f-to-f offering – considering the fact that though she quite likely was queer, she was also very oblique about it – what I’ve heard called “old school.” Here’s a passage from that Paris Review interview cited here without value judgment – neither for Yourcenar nor her interviewer and his “deviance:”