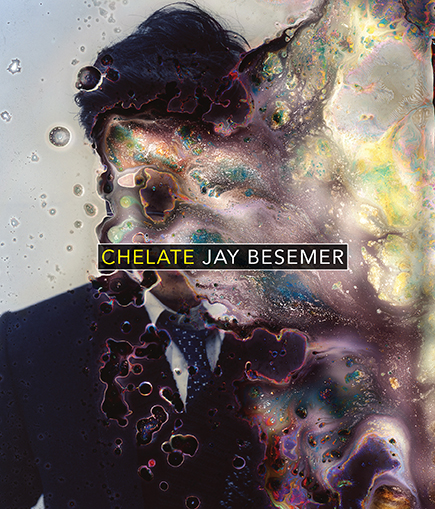

RE:CONVERSATION :: CHELATE :: QUEERING THE TRANS POETIC with JAY BESEMER

[line]

[line]

[articlequote]Written during the advent of hormone therapy and gender transition, Chelate by OS Contributing Editor Jay Besemer (out July 1 from Brooklyn Arts Press) explores the journey towards a new embodiment, one that is immediately complicated by the difficult news of a debilitating illness. This engaging chronicle speaks powerfully and poetically to the experience of inhabiting a toxic body, and the ruptures in consciousness and language that arise when confronted by a stark imperative, and choosing to live, and to change. The book moves intermittently from exile and alienation to hopeful anticipation, played out in short bursts of imaginative dreamwork, where desires eventually give way to their realities, as the self begins mapping the permutations of its momentous shift. What begins in uncertainty and commitment ends in self-recognition, and more uncertainty, but now in a necessary space unified by will, love, action, process, and documentation.

This is a striking, critical space and one we wanted to get the chance – and give Jay the chance – to explore further with our community, so today we have our classic author/poet Re:Conversation — questions on poetics and process — on CHELATE and on Jay’s work in general. We’re so happy to have him here. – Lynne DeSilva-Johnson

[/articlequote] [line]

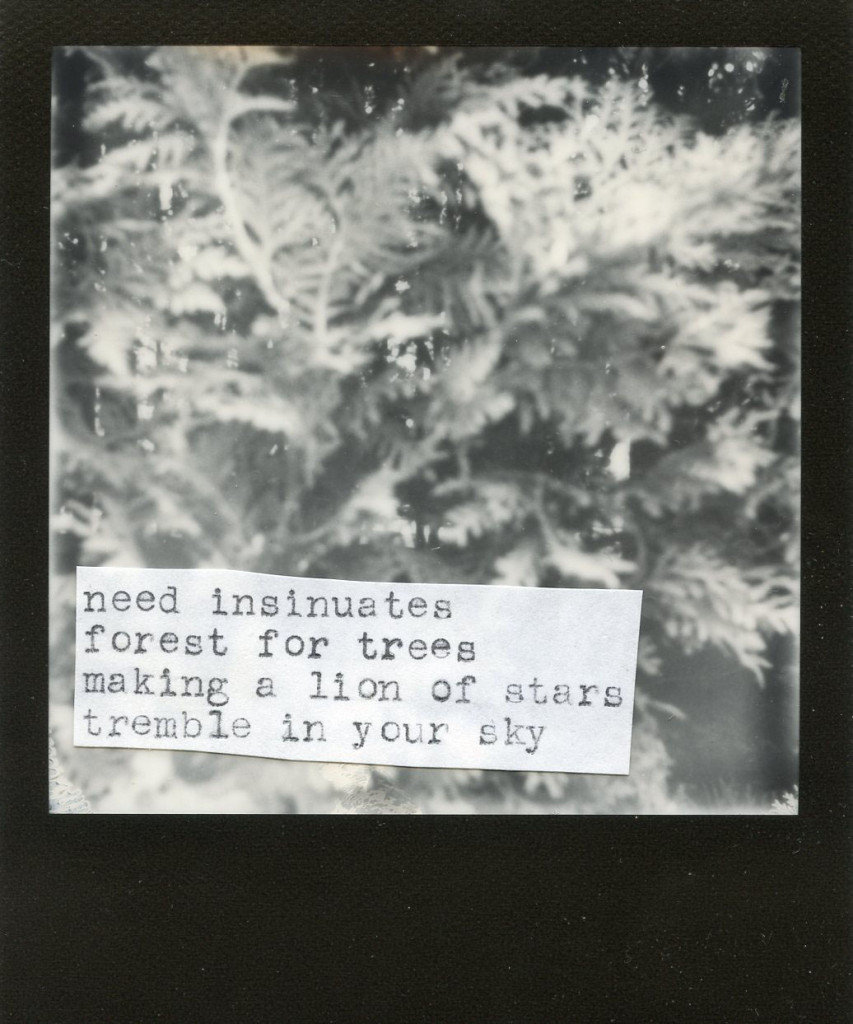

excerpt:

[line]

[line]

Hi Jay! Let’s just start with the very basics, for those who might not know: who are you?

My full name is Jay Andrew Besemer. I’m a hybrid artist, a queer-identified middle-aged trans man, and I live with multiple intersecting chronic illnesses and neurological realities that, in ableist society, disqualify me from some privileged modes of participation and production.

Why are you a poet?

There’s no single reason, other than that I can’t not be a poet. After over 30 years of daily poetic practice—and professional poetic career-building—I’m finally realizing that I process the world through writing/making, particularly through making poetry. Naturally over these decades my relationship to poetry has changed, and so has what I need from poetry. I’m also beginning to recognize what poetry needs from me.

When did you decide you were a poet (and/or: do you feel comfortable calling yourself a poet, what other titles or affiliations do you prefer/feel are more accurate)?

I began writing poetry in a dedicated way when I was 13, and it took about a year for me to recognize that this was going to be my life. The only other thing that I’ve ever wanted to do (as a lifepath) with that amount of certainty was to act. I didn’t wind up being an actor exactly, but performance is part of my practice.

I call myself a poet, as a shorthand, but that’s not to exclude the rest of what my practice involves. That’s why I say I’m a “hybrid artist,” and also why I say I “make” poetry rather than “write” it. My poetic starting point is not always pen-to-paper. When it is, it’s literally that—I draft in ink or pencil, on paper. I am a bit fetishy about fountain pens and notebooks. I also make poems using source texts (i.e. collage, erasure) and constraints or other processes (i.e. Markov-chain derived poetry). Much of my work combines still or moving images with text, like my video and photo poems.

[line][box][articlequote]I guess a poem-making poet does so from a space of acceptance; human language can’t possibly work the way we try to get it to work, and we know that, and can’t stop ourselves from trying anyway, or from loving the language. We can’t even really control language, but the act of surrender to the state of unknowing and to language itself, that material that flows in and through and around us, makes life worth living. I say it that way because not all poets produce on-the-page poems, or not all the time—there’s a way in which a poet is also sometimes a person who makes of life what others might call a poem. Substitute “life” for “language” above and you’ll see what I’m getting at. Sometimes one person is both kinds of poet.[/articlequote][/box][line]

What’s a “poet”, anyway?

I am not sure I know. I guess a poem-making poet does so from a space of acceptance; human language can’t possibly work the way we try to get it to work, and we know that, and can’t stop ourselves from trying anyway, or from loving the language. We can’t even really control language, but the act of surrender to the state of unknowing and to language itself, that material that flows in and through and around us, makes life worth living. I say it that way because not all poets produce on-the-page poems, or not all the time—there’s a way in which a poet is also sometimes a person who makes of life what others might call a poem. Substitute “life” for “language” above and you’ll see what I’m getting at. Sometimes one person is both kinds of poet.

What is the role of the poet today?

Well, there’s no single role, eh? I mean, I can’t make that call for anyone but myself.

What do you see as your cultural and social role (in the poetry community and beyond)?

I think that in the experimental, queer, trans, mad/sick sliver of the Venn diagram in which I operate, “culture” means something different than it does to institutions, media outlets, funding agencies, consumers and publishers. Of course, I am also a publisher to some extent, through working with you and The Operating System, and my work with Nerve Lantern: Axon of Performance Writing. And I run my own very well-named Intermittent Series for poetry and micro-performance. And I’m a critic, which I see very definitely as an act of service to the community, especially since I focus mainly (in poetry reviews and other critical engagements with poetry) on books by trans/genderqueer/nonbinary/intersex poets, poets of color, disability-spectrum poets and poetics, queer poets and poets’ first books.

That’s sort of official-sounding, but there’s a lot of informal networking and sharing in and beyond the official capacities outlined above. I assisted a friend in finding a publisher for his book. That same friend published a scroll-book by another poet friend, a piece he heard performed at a chapbook release party for me. Those are just two examples of a type of mutual-aid behavior that I find important to my overall practice. I devote a lot of my time and energy to this because I believe poetry is communal, cooperative, not competitive. The competitive, fear-driven scarcity mentality one sometimes sees in the po biz is a distortion. I have my own insecurities and needs for validation and approval, certainly, but I believe that your success is my success, especially when you are traditionally on the margins or not privileged by mainstream or normative valuation. When I go to bat for your work, in whatever way that manifests, it’s an act of love—for you, for me, and for poetry. Love is never failure.

Beyond the poetry community I have two roles as a poet:

To show by example that another way of life is possible, though perhaps not easy. That’s for everyone. To show younger queer/trans/mad/sick creatives that they too can make a life with their art. Even if they have to find their own ways through, some others like them have cleared many of the biggest obstacles (or at least put up markers warning of their existence).

Talk about the process or instinct to move the poems in CHELATE as independent entities into this body of work. How and why did this happen? Have you had this intention for a while? What encouraged and/or confounded this (or a book, in general) coming together? Was it a struggle?

CHELATE is my third published full-length collection. It is rarely a struggle for me to write. It’s a struggle for me to do much else, really. CHELATE actually didn’t involve a process of “moving independent entities into a body of work.” In demarcation of the boundaries of the collection, it’s less a matter of coming together or collection or compilation, and more like deciding how much hair to cut.

The “body of work” phrase fits very well here, though, because CHELATE is a book that lives in/is/is from the body. I mentioned before that I make poems as a way of processing the world around me. That means specifically that I use poetry as a mediating structure, but also as a mode of analysis and coming-to-understand (or at least to recognize) perceptions and experiences. In a real sense, poetry is another body. Any book of mine is therefore both of my body and an extension of (or a different version of) my body.

The “body of work” phrase fits very well here, though, because CHELATE is a book that lives in/is/is from the body. I mentioned before that I make poems as a way of processing the world around me. That means specifically that I use poetry as a mediating structure, but also as a mode of analysis and coming-to-understand (or at least to recognize) perceptions and experiences. In a real sense, poetry is another body. Any book of mine is therefore both of my body and an extension of (or a different version of) my body.

This is especially true of CHELATE, because it was written as an externalization of the internal disorientation, fragmentation and adjustment involved in early-stage medical gender transition. I wrote the book before and at the beginning of hormone therapy; during the course of routine blood work for monitoring the effects of testosterone, I was diagnosed with one of the chronic illnesses I live with (the others were long a part of me). So not only was CHELATE the result of navigating an urban, neoliberal capitalist socius in a socially illegible body, it also was the result of adjustment to living in a sick body. Some things about myself I was certain of, but they were largely in the negative: not a woman, not heterosexual, not totally healthy, not desirous of the things I was “supposed to” want. I didn’t know how to live while globally ill, nor did I particularly know what kind(s) of man I would like to be, or even the degree to which I then wanted to or would want to embrace “man” as a self-description. So I let that wild disorientation be the book.

Did you envision this collection as a collection or understand your process as writing specifically around a theme while the poems themselves were being written? How or how not?

When I write pen-and-paper poems I shape each book from a large number of raw poems organized roughly in chronological order. Each book of that type is generally representative of a period of time, a kind of anti- or queered nonlinear documentary in poetry. I feel like that sounds cheesy. What I’m getting at is that the books are already always a collection.

In pen-and-paper poems it’s a matter, as I said, of deciding where to cut the hair. At what point in time does the book tell me it’s finished? In project-focused books each collection contains its own boundaries; an erasure project won’t extend past the end of the source text, for example.

Speaking of monikers, what does this title, ‘CHELATE’ represent? How was it generated? Talk about the way you titled the book, and how your process of naming (poems, sections, etc) influences you and/or colors your work specifically.

Chelation is a chemical process used in medicine to treat metal toxicity (i.e. lead or iron poisoning). It transforms the toxic elements so they no longer harm the body. The title CHELATE is taken from a phrase in one of the poems in the book, in which I “chelate myself into a new man.” I draw a clear parallel between multiple medical procedures to treat the toxic body, linking chelation (as transformative biochemical process) to both hormone therapy and the action of other medicines that work in my body to keep certain substances to a non-toxic level (and make up for the lack of other substances).

Section titles in CHELATE reflect elements of my life and psyche ongoing at the time of writing the book. Most of the time, titles of books come from the poems themselves. Section titles in books can also, but many do not. I did not title individual poems in CHELATE; there are many reasons for this. In many ways the book is one big poem—at least I experienced it that way while working on it, as one big now. It didn’t feel appropriate to title each section of now. It would have been overstimulating too—there’s so much sensory input in the book, a swarm of titles would have drawn undue attention and pulled readers away from the immediacy of the experience of reading, and into distracting “meaning-hunts.”

In some ways sections are mini-books. This is actually true for other ongoing projects that combine related chapbook-length collections/texts. For those I retain the individual titles of those texts. One example of this is also found in CHELATE, with the first section, “Xenophilia.” This part started out as a chapbook and then became as unstoppable as a July zucchini vine—it became the rest of the book.

Let’s talk a little more about your language use in general. CHELATE has this incredible way of feeling very lyrical, like a nature poem — and yet very clearly engages scientific language and obscure, and/or technological references, “saurischian,” “elastoplast,” “travertine,” as well as colloquial phrases and depictions of modern life. The effect is not dissimilar to Carson’s tone in The Autobiography of Red or to reading a Margaret Atwood novel – a subtle collusion of storytelling and phrases familiar from myth with scenes from a suddenly present future. Given my proclivities towards all these things, it’s a comfortable space for me.

Thanks for the Carson comparison! Love her Red books; in fact I’m rereading them now, but I was not aware of being directly influenced by them when CHELATE was happening. I think I see what you mean by tone and I agree with the “nature poem” comparison.

My early years as a poet involved a lot of reading of poets like Issa and Basho, who were distilling very massive earth-based experiences into tiny potent language moments. That’s still in me, and I experience my life and identity as inextricable from the world around me; from the earth and the cosmos and the invisible but measurable energies and forces and fields that shape (and manifest as) matter. In my earlier life I was also actively involved in the sciences, as a research assistant and information specialist for the late biochemist and inventor, Dr. Leland C. Clark, Jr. So yeah, that is a lineage that soaks my work and my language.

Oh, and you don’t ask this, but I think it should be said: I am a passionate fan of science fiction in most forms. Readers who suspect references to various SF franchises, authors or concepts are probably right. And Samuel R. Delany is one of the biggest non-poet influences on my recent poetry.

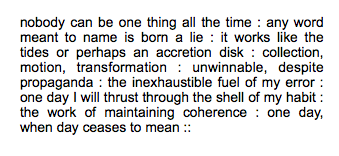

Same here. I’m always sort of confused when people don’t love science fiction – that space of discovery, of curiosity, of what comes next – it’s very poetic in its inquiry, even when the language is not. Sticking with language for a second — in the excerpt above, you write: “nobody can be one thing all the time : any word meant to name is born a lie.” Can we dig a little deeper into this, or this as it appears in the book at large?

I’ll expand on that segment if you like. It’s a refusal to be limited either by a gender binary or a name—or a “read”—someone else gives me. What another person thinks I am and tries to impose on me is not what I am. I fit even less into categories established by a government, an institution, a document or an application form. For most of my life I killed myself by trying to fit. No more. So I may identify as a man, but only I get to set the parameters of that, and only I get to experience the richness of it as the multiplicity I actually am.

[line][box][articlequote]The book engages much more of my personhood than the physical process of transition. I’ve queered the “trans book” by allowing the language to serve me rather than an audience expecting something standardized and simple. I am a critical thinker and a feeler, a deeply spiritual person and a person newly emerging into bodily pleasure in a way that was never before accessible to me. I am also a person whose thought processes, perceptions and sensory experiences are—I’ll claim this proudly, positively—abnormal. But the daily flow of living with all of that is very private. The choice of whether and how to language it is and can only be my own. Likewise, my body, my genitals and what I do with them are no one else’s truth and no one else’s entertainment. [/articlequote][/box][line]

What I also find myself drawn to question or eke out a little more about from you is your approach in speaking to, if around, the book’s “subject,” if you could call it that, insofar as details — or, more precisely, anticipated *vocabulary* around sexuality, gender, and surgery is largely absent. This isn’t to say at all that you’ve not spoken quite directly to the experience of the experience, but that you’ve done so using a carefully curated language much more your own (it seems), in which there’s enormous ownership of the spaces between as much as of definition. To what extent is this intentional? I know you and I both live in queer definition, and you’ve spoken to this as a personal label above, but can you talk about how this affects the language in these poems, and your poems in general?

Well, there’s a lot of expectation in the normative world that a book centering “the” trans experience (I’m trying not to sneer too loudly at that phrase) will contain recognizable, reassuring, normalizing experience-language signposts for them to consume/subsume. There’s a similar thinking that trans lit is limited to transition narratives or to first-person-singular, author-is-narrator, “self-expression” approaches to poetry. However, none of that reflects or has any room for my personal experience of transition. These expectations are only attempts to impose a master narrative or a master language onto trans people from the outside. I am more than my body, my genitals, my hormones. Everyone is. Yet trans people are regularly reduced to bodies, and especially to genitals and hormones, in public and private discourse. This reductionism is also present in the expectations held for our creative output. Sometimes it’s even internalized by trans authors and audiences ourselves.

The book engages much more of my personhood than the physical process of transition. I’ve queered the “trans book” by allowing the language to serve me rather than an audience expecting something standardized and simple. I am a critical thinker and a feeler, a deeply spiritual person and a person newly emerging into bodily pleasure in a way that was never before accessible to me. I am also a person whose thought processes, perceptions and sensory experiences are—I’ll claim this proudly, positively—abnormal. But the daily flow of living with all of that is very private. The choice of whether and how to language it is and can only be my own. Likewise, my body, my genitals and what I do with them are no one else’s truth and no one else’s entertainment.

Also (and this is vital to me), the masking or coding in my language is a refusal of any assumed right to interrogate me, whether by active or passive means. The demand made by a cis person or a healthy person to “hear my story” is invasive. I am not a fetish nor am I a fascinating problem to be understood. No one has a right to full access to my private experiences. Putting the language out there on my own terms was the only way to create the powerful safety that made the book itself possible.

You have to understand how absolutely vulnerable and raw I was when writing CHELATE. My current work is more direct. I’m letting some of the above moves come through more legibly, not for others’ sake or convenience, but because I am more used to living in this embodiment and I am better prepared to support my own truths. But lately I am finding that it’s best to let the deep anger I’ve felt come through in my language; in fact, more and more emotions are closer to the surface and more legible to me, so they are getting into my language more directly.

What does this particular collection of poems represent to you

…as indicative of your method/creative practice?

…as indicative of your history?

…as indicative of your mission/intentions/hopes/plans?

CHELATE is a container for one specific part of my body’s history, and the history of my selfhood. This is about authenticity, which is also related to the question about intentions/mission. People talk about authenticity in a therapeutic context, and then they use the word differently in a poetic context to mean that the I in the text is close to the author’s own self, if not identical—and the word “history” crops up in that conversation too. But CHELATE’s authenticity and historicity are not that simple, even though the connection to my selfhood is direct. My “i” isn’t always trustworthy (“authentic”) and it isn’t always what you’d recognize as belonging to me.

Let me talk about form. Here’s where life and art become meaningfully blurred together. Before I could feel able to physically transition, I had to create a conceptual form—a new conceptual body—for myself. As far back as my first published full-length book, TELEPHONE (also from Brooklyn Arts Press) I found that to go where I needed to go in my work, I had to invent an idiosyncratic prose-poem form and punctuation mode to contain the fragments of text that were coming out onto the page.

Let me talk about form. Here’s where life and art become meaningfully blurred together. Before I could feel able to physically transition, I had to create a conceptual form—a new conceptual body—for myself. As far back as my first published full-length book, TELEPHONE (also from Brooklyn Arts Press) I found that to go where I needed to go in my work, I had to invent an idiosyncratic prose-poem form and punctuation mode to contain the fragments of text that were coming out onto the page.

Just as in preparing to transition, I needed to make a new textual space or make new use of the page before the things that needed to be there could even manifest. It couldn’t look like a more recognizable prose poem, with standard syntax and mechanics of capitalization and punctuation. I had tried that and the result just couldn’t hold up to even my own preconceptions about how a prose poem works, which were activated by the cues of the more standard form. So I just stripped everything away and was left with the problem of reading, specifically the breath. How could I let myself and other readers know when words needed pauses? I came up with the idea of using single and paired colons to show short pauses and full stop-and-consider rests. CHELATE carries this form. I am moving away from the need for that type of custom form right now, but I still favor a loose prose-block for much of my poetry.

Curiously, I also began using double colons a few years ago; it’s always interesting to see parallel invention totally unaware of others’ similar evolution or use. What formal structures or other constrictive practices (if any) do you use in the creation of your work? Have certain teachers or instructive environments, or readings/writings of other creative people (poets or others) informed the way you work/write?

You already know of the influence of the whole body of Tristan Tzara’s work on my own work. I’ve mentioned a lot about my work processes, constraints/procedural writing, and hybridism. But I’m in a kind of renaissance as a maker; over the last four years or so since the original call went out for the anthology Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics, edited by TC Tolbert and Trace Peterson, the feeling of coming home—and of acceptance and permission—allowed not only a personal transition to take place for me, but a creative one too. I suddenly had a community of other trans poets (experimental poets, to a large degree!) who validated my own work and selfhood simply by existing and working.

So all my anthology-mates have been big influences on my renaissance, on my current work. Among those I’ve become close with TC, Trace, Max Wolf Valerio, j/j hastain (with whom I’ve collaborated since before the anthology) and Zoe Tuck. I’ve also been influenced by Ching-In Chen, Micha Cardenas and CAConrad in both personal and work-related ways.

My Chicago poet friends are deeply important to my work, as companions and inspirations and siblings. Sometimes simply being with them gives me a new idea or gets me unstuck. To name-check, I’m talking about Nicholas Alexander Hayes, Toby Altman, Laura Goldstein, Alix Anne Shaw, Cean Gamalinda, Joe Proulx (who just moved to NYC), Daniel Borzutzky, and others involved with the Absinthe & Zygote series, Meekling Press projects and Red Rover Series [Readings that play with reading]. There are some non-local poets I haven’t mentioned above who are very close, including Simeon Berry.

I am also deeply influenced by people who are perhaps not only or not primarily poets, but who also work in and around performance or other hybridisms (two of whom are also friends). I’m talking about Petra Kuppers, Stephanie Heit, Matthew Goulish, Guillermo Gomez-Peña, Bhanu Kapil, Jennifer Bartlett, and Claudia Rankine.

Some presses are very important to me and my work, even if they aren’t ones who’ve published me before. Essay Press and Plays Inverse are two such and I read their offerings hungrily. At various times I’ve been inspired by what I’ve learned from publications like BOMB, The Drama Review (TDR), Art Papers and Aperture, to which I subscribe currently. And there are actors who are particularly important to me, either for their body of work or their approach to acting/life, or both.

[line][box][articlequote]I’ve really been confronting different privilege systems since beginning the transition process two years ago. Because of the direction of my transition, I am a man who was raised with no experience or expectation whatsoever of male privilege. In fact my experience as a whole pre-transition has not led me to expect any sort of privilege at all—or to be aware of it when it worked in my life (i.e. to be aware of the armor my skin color provides). So when I experience it now, it causes a weird complex of reactions. I’m uncomfortable with some of the unearned respect I’m shown, but I’m also relieved by it, especially since it largely comes from the same people or in the same situations as those in which I was shamed, dismissed or dehumanized when I was less legible as any gender. That’s a hard thing to bear. I’ve moved in one sense from abjection to imposed (not assumed) privilege with no preparation and no experience of a middle ground![/articlequote][/box][line]

Let’s talk a little bit about the role of poetics and creative community in social activism, in particular in what I call “Civil Rights 2.0,” which has been continuously, immediately present all around us in the time leading up to this book’s publication. I’d be curious to hear some thoughts on the challenges we currently face in speaking and publishing across lines of race, age, ability/access, privilege, social/cultural background, and sexuality within the community, vs. the dangers of remaining and producing in isolated “silos.”

Recently there was a little Twitter exchange in which Wendy Xu wondered what would happen if white poets refused to perform in all-white readings of three or more people. I found that compatible with decisions and actions I’ve been taking in my own public poetic life, so I retweeted with a comment to the effect that I am prepared to do that, and to go one further by making resonant choices when organizing events and/or requesting co-readers. But to be totally honest, I’m not sure how much I can control or counteract the conditions she’s talking about with her question. I’m one queer trans sick white man, and I perform so rarely, and curate irregularly. What kind of impact can I hope to make? How consistent can I really expect myself to be? I know the point is to try, but I’d like to do more than that. The question got me thinking, or rather it helped crystallize some recent thinking.

I’ve really been confronting different privilege systems since beginning the transition process two years ago. Because of the direction of my transition, I am a man who was raised with no experience or expectation whatsoever of male privilege. In fact my experience as a whole pre-transition has not led me to expect any sort of privilege at all—or to be aware of it when it worked in my life (i.e. to be aware of the armor my skin color provides). So when I experience it now, it causes a weird complex of reactions. I’m uncomfortable with some of the unearned respect I’m shown, but I’m also relieved by it, especially since it largely comes from the same people or in the same situations as those in which I was shamed, dismissed or dehumanized when I was less legible as any gender. That’s a hard thing to bear. I’ve moved in one sense from abjection to imposed (not assumed) privilege with no preparation and no experience of a middle ground!

At the same time, I’ve experienced a loss of privilege that some people (across class, gender, sexuality, or skin color) can take for granted: health. I’ve had to learn exactly what it means to live with manageable but incurable, serious, unpredictably degenerative, chronic illness. It changes everything. Illness makes it difficult to participate as actively as I would like in both my own career (getting work out there, promotion) and in the community-fostering projects involving publishing/curating/supporting others’ work.

At the same time, I’ve experienced a loss of privilege that some people (across class, gender, sexuality, or skin color) can take for granted: health. I’ve had to learn exactly what it means to live with manageable but incurable, serious, unpredictably degenerative, chronic illness. It changes everything. Illness makes it difficult to participate as actively as I would like in both my own career (getting work out there, promotion) and in the community-fostering projects involving publishing/curating/supporting others’ work.

I can’t tour, and conference/residency/retreat attendance is unlikely for me, especially if it involves travel. My immune system and my energy levels can’t take it: a four-day conference (including round-trip travel) requires weeks of recovery afterwards, and that turns into months if (as usually happens) I get a virus in the process. Of course, that’s just the physical limitations; any travel I undertake must be domestic, as I still can’t get a passport with the correct gender marker. And I have no money, and no energy for filling out endless grant applications. Many of the opportunities for participation and contribution are multiply inaccessible to me. Even if I fall into a vat of cash or achieve total documentation accuracy, I’ll still be sick.

So this is the space from which I make my own work, edit/publish/promote/curate others’ work, and move about in the world, living my life. Illness sometimes “silos” me, against my will. Taking steps to get out of that sequestered state, even just in a virtual sense, responds to my need for companionship and support, but it also comes from an impulse to give of myself, to offer what I can. I need to contribute. One way of doing that, for me, is to actively seek out and work with other people from the edges of the privilege spectrum, I guess you could say. It’s a process. It’s not something I’m good at (I’m also an introvert!) but I hope that means I can stay teachable.

As someone who struggles with chronic illness, and queer visibility issues, as you know well, you’re speaking my language. Let’s talk for a minute, too, about another type of language: nonverbal. You describe yourself as a hybrid artist, and you work in a variety of forms both analog and digital. Do you feel that your interdisciplinary practice has informed the form you use as all, and/or if perhaps the form you developed for TELEPHONE and CHELATE? Can you tell us a little more about your work in other mediums in general? I’m curious to know if perhaps seeing the page as a visual artist as well as as a poet is something you think has had a striking influence on how the poems themselves eventually have come to be not only designed and laid out but eventually generated, and how (I think for sure this is true in my case).

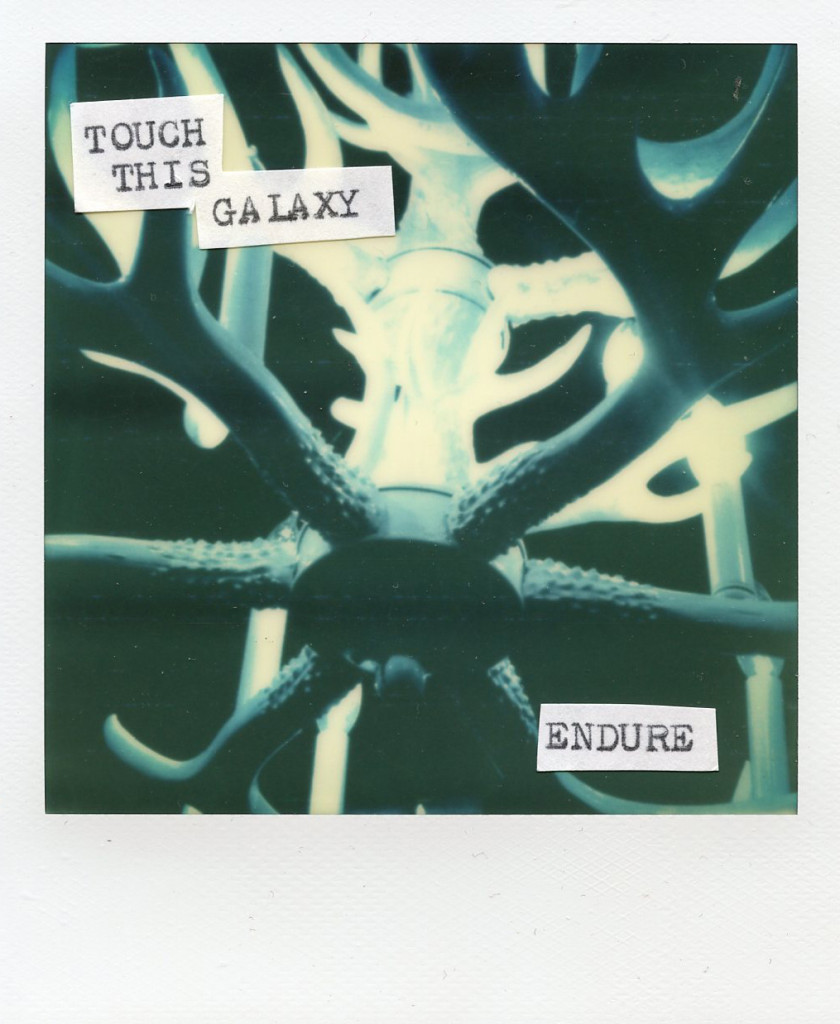

Good question. I’d have to say yes about the page. I’ve recently wondered if the squarey block prose form is related to the Polaroid instant photos I’ve been making for the last 5 years or so. I happened to notice that the size of the poem on the page is almost identical to that of the Spectra-format instant photos I tend to favor! This was a very amusing discovery. I’ve made photos (not Polaroids though) even longer than I’ve made poems, so if there’s a connection it’s deep. A way of composing an image using language rather than light or a physical medium.

This is a really ambitious and important volume, for so many reasons, and I’m so thrilled to see it making its way into the world. What are your hopes for the book, as it enters public awareness? Do you have any plans for helping it reach certain audiences and/or intentions for its use as a community tool? Are there any events or public readings that we can go to, or anything coming up you’d like to share? And what’s next on your agenda?

Thanks for saying so! To be honest, I have a great deal of difficulty projecting hopes and ambitions onto my work. I have no particular plans for putting it before certain audiences or using it as a community tool. Also, for reasons I’ve stated earlier, I believe it isn’t well-suited to be an ambassadorial book. It was not meant to be. Nor am I well-suited to be an ambassador. While I do hope that someone who needs it finds it on their own and recognizes something nurturing in it, I can’t hold the expectation that it would function in this way. However, I have a strong suspicion that certain of my friends in academic contexts might teach it. (Hi Trace, hi TC!) And of course I will promote it according to my own capabilities, alongside my publisher.

Most of the readings involving the book will be in the Chicago area in the fall and winter of 2016/17, and are being scheduled right now. The best thing to do for updates on CHELATE events will be to check out my social media (Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook) and follow, like, whatever:

https://twitter.com/divinetailor

http://jaybesemer.tumblr.com

https://www.facebook.com/jaybesemer

What’s next? I keep writing. I have so many ongoing projects right now—I’m working in experimental prose and poets’ theatre currently but have also recently finished two full-length poetry books. I’d also like to prioritize my Intermittent Series (there have been some nibbles) and move forward on some video and OS curatorial projects! I’ve also got some ongoing collaborations that have been interrupted…

All of this is health and life-circumstances permitting, of course!

Thank you!

——-

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/1459900974087-e1467206127648.jpeg[/textwrap_image]Jay Besemer –

Jay Besemer is the author of many poetic artifacts including Telephone (Brooklyn Arts Press), A New Territory Sought (Moria), Aster to Daylily (Damask Press), and Object with Man’s Face (Rain Taxi Ohm Editions). He is a contributor to the groundbreaking anthology Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics. His performances and video poems have been featured in various live arts festivals and series, including Meekling Press’ TALKS Series; Chicago Calling Arts Festival; Red Rover Series {readings that play with reading}; Absinthe & Zygote; @Salon 2014 and Sunday Circus. Jay also contributes performance texts, poems, and critical essays to numerous publications including Nerve Lantern: Axon of Performance Literature, Barzakh, The Collagist, PANK, Petra, Rain Taxi Review of Books, The VOLTA, and the CCM organs ENTROPY and ENCLAVE. He is a contributing editor with The Operating System, the co-editor of a special digital Yoko Ono tribute issue of Nerve Lantern, and founder of the Intermittent Series in Chicago, where he lives with his partner and a very helpful cat.

[line][line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]