[RE:CON]VERSATIONS :: COMPLICATED WORK :: Exploring "A GUN SHOW" with Sō Percussion's Adam Sliwinski

[line]

[box]In a conversation with composer, percussionist, conductor and educator Adam Sliwinski, we take a deeper look into A GUN SHOW, which brings together his critically acclaimed percussion ensemble Sō Percussion with Three-time Obie-winning director Ain Gordon and performer Emily Johnson to explore America’s fraught relationship with guns. Taking mallets to disassembled sniper rifles and assorted drums, the musicians serve as Greek chorus, commenting instrumentally on sung and spoken texts drawn from the nightmares and nostalgia of armed experiences, in a probing work in which anger meets inalienable rights, dark memories resurface, and a contested weapon sings a bittersweet song.

OS Founder and Managing Editor Lynne DeSilva-Johnson has been working with Adam, the members of Sō Percussion and their highly visionary collaborators on documentation of this important piece — and the processes of its making — for a book to be released in tandem with A GUN SHOW’s premiere at the BAM Next Wave Festival, 2016, Nov 30 – Dec 3. More information on the performance and tickets can be found here. [/box]

[line]

[articlequote]How do you even begin to make art about such a complicated subject? The emerging answer was that you make complicated work. – Adam Sliwinski [/articlequote] [line]

[line] Lynne DeSilva-Johnson: It’s hard to even begin to describe this piece, in language that feels adequate, in a time like this. That said, can you give us your elevator pitch? IE: what is ‘A GUN SHOW,’ in a few sentences?

Adam Sliwinski: The ways in which Americans perceive guns seems to intersect with numerous serious issues that confront our society – race, economic inequality, public safety, constitutional rights. A Gun Show is an exploration of these issues through music, text, and movement.

LDJ: What was the impetus that originally drove you to start developing this piece?

AS: After Sandy Hook, we were all devastated. My stepson was exactly the age of those children from Newtown, and there was something about that shooting that just pierced you when you heard about it. We’ve long been interested in the idea of Art as a response to social issues…perhaps not a responsive action, and definitely not a substitute for action, but more of a way to process our humanity. We realized that it wasn’t just these dramatic mass shootings that brought the gun issue out. The culture itself was saturated with their use and imagery.

We’ve all had different experiences with guns. Some of us, like Josh or Emily, grew up in rural areas where they are commonplace. Others, such as me, grew up mostly in suburbs where they really weren’t present. My views on guns were formed mostly as political views. I never had that human-object relationship with a gun that many others have, or that I have with one of my musical instruments.

[line][articlequote]Many of our percussion instruments, which we have such a joyful relationship with, were originally used as instruments of war. They have potential violence embedded in their very nature. [/articlequote][line]

We began researching, talking, and making work. Many of our percussion instruments, which we have such a joyful relationship with, were originally used as instruments of war. They have potential violence embedded in their very nature. That seemed to provide a bridge from the issue to a work of music theater.

LDJ: Who was involved at that point? Did you already have a vision about what sort of collaborations you envisioned? I imagined it evolved organically, as these things always do, but can you tell us a little bit about its early genesis and first steps?

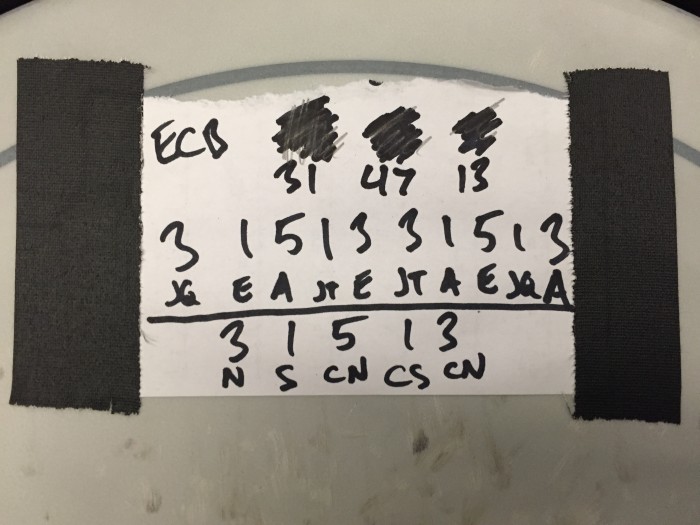

We decided very quickly that Ain and Emily, who we worked with on Where (we) Live, would be the perfect collaborators for the next project. They had the taste and sensitivity to tackle this difficult subject. The first steps evolved out of sidebar collaborations. Emily and Josh wrote texts independently of each other, then began combining them into something more ambiguous. Jason fixated on the number of gun related deaths in a recent year (31513) as a structural building block for new abstract rhythmic compositions.

Many of the pieces in A Gun Show reflect abstract concepts and emotional states. This was often the only way we could wrap our heads and hearts around such a fraught subject. More than any other project, we really didn’t know what eventual shape it would take. How do you even begin to make art about such a complicated subject? The emerging answer was that you make complicated work.

Almost any time we tried to say something definitive about gun violence, it felt reductive. The ultimate reduction is the NRA’s assertion that “guns don’t kill people, people do.” Every time one of our statements started to approach that level of simplicity, we recoiled.

LDJ: Tell me about your role in these early conversations – and in the piece’s development.

There’s certainly a good deal of interplay between influences, story, and reflection on personal experience – talk a little about how you all, as collaborators, brought your history / reflections / emotions into framing the piece. How and when were other collaborators brought on, and how did they become involved?

AS: Yes, there is. As I wrote above, Emily and Ain were involved very early on. Our emotions and reactions to the gun issue could probably be grouped into several categories: personal, political, artistic.

Politically, we are mostly aligned with the prevailing educated urban viewpoint: that responsible regulation should be assertively applied in trying to curb the number of people who suffer from gun violence.

Personally, our experiences were all over the map. But these memories and impressions became a key part of making the work, as we realized that any attempt to reduce the issue as it affects other people felt wrong.

Artistically, there lingered this issue of what art can actually DO when it comes to a political or social issue like this. Leonard Bernstein has a quote that gets trotted around on Facebook whenever a gun tragedy or terrorist attack happens: “This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.” I’ve always hated it, and working on this show gave me cause to analyze that reaction.

Bernstein was responding in the wake of the Kennedy assassination, so I think it’s a bit unfair to hold him to this quote. He was a deeply intelligent and sensitive communicator.

I think if Bernstein’s quote were slightly altered, I’d agree with it.

“Despite the pervasiveness of violence in our society, we will continue to make music even more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.”

There is something definitive about Bernstein’s wording when he says “this will be our reply.” It suggests an attitude that was much more prevalent in his day among artistic and social elites, that art had the direct social purpose of ennobling humans and making them somehow “better.” According to this mindset, making and experiencing great art could in some sense directly address social problems. This premise is dubious, and it doubly bothers me because it funnels art towards a purpose that doesn’t always suit its strengths.

For me, art can fill in the cracks of human experience. That DOES NOT require it to always be noble or transcendent. In fact, art often creates problems in the sense that it addresses complexity through images and sounds that are difficult to speak about (just ask Wittgenstein).

My alteration of Bernstein’s quote suggests that art provides us with an opportunity to demonstrate our resilience and determination not to be intimidated by violence and terror (domestic or foreign). I secretly think that this is more or less what he was getting at.

[line][articlequote]Artistically, there lingered this issue of what art can actually DO when it comes to a political or social issue like this….For me, art can fill in the cracks of human experience. That DOES NOT require it to always be noble or transcendent. In fact, art often creates problems in the sense that it addresses complexity through images and sounds that are difficult to speak about…[but in so doing] provides us with an opportunity to demonstrate our resilience and determination not to be intimidated by violence and terror (domestic or foreign).[/articlequote][line]

LDJ: I think what may be difficult to parse for the general public is the ways in which each of you brings these elements not only to the concept of the show and its staging, and then to visual and textual factors within the production and its framework, but also to the composition of the percussion arrangement, itself.

AS: The primary symbolic importance of percussion in our performance is that many percussion instruments were originally designed to facilitate violence. After a delicate opening in which a quiet piece for snare drums is performed with the drums removed from our hands, the entire ensemble begins a Bolero-like accumulation of drum patterns that clearly references gun and cannon-fire. Our “chorus” of 8 percussionists returns to this role periodically throughout the show.

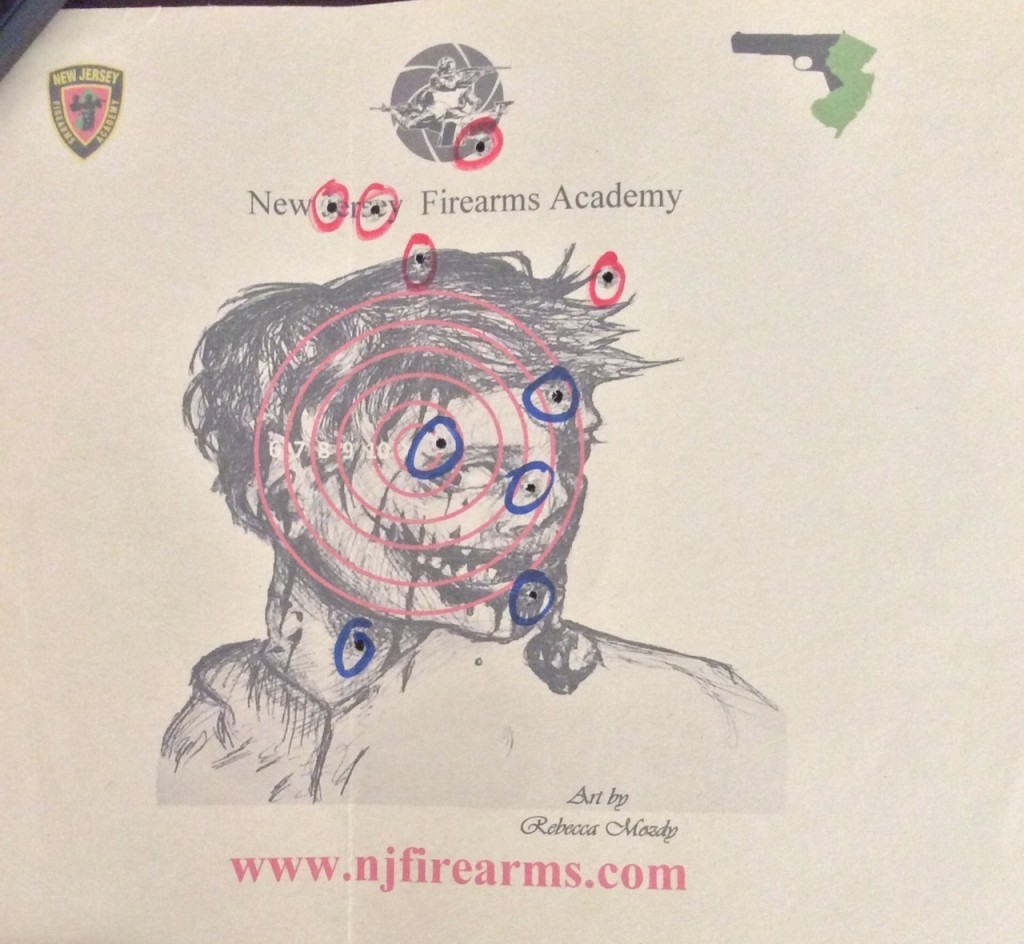

At other times, we force symbolic objects to become percussion instruments. Josh ordered pieces of decommissioned Russian sniper rifles online, which we Velcro-ed to tables in order to play. Many of the metal parts sounds surprisingly good. This is perhaps a small gesture towards “beating swords into plowshares, and spears into pruning hooks.”

Towards the end of the show, Josh hoists a large tam tam so that Emily can play it. Yellow cables splay out down the inclined stage, connecting to guitar pedals that turn the sound on and off. The tam tam doesn’t have a specific reference, but Josh’s struggle in carrying it connects the vibrations of the instrument to the spider-like cables, and the performers filter the intensity of that sound.

LDJ: Are all members of the ensemble equally involved in the composition process? Talk a little more about the development of a piece — especially when it has conceptual elements, like this one — how much do (and, in compositional, instrumental, musical terms how do) these influences come to bear on this process, collaboratively or individually? How has the influence of other, non-percussion based collaborators changed or directly influenced the evolution of the piece?

AS: This is a good opportunity to address Emily Johnson’s role in the process. She is a co-creator of the piece, and we talk about her contribution mostly in terms of “movement,” although she also wrote some of the texts and contributed musical ideas. The word “choreographer” doesn’t really suit our concept of what she does, because it too easily brings to mind a very limited idea of what dance looks and feels like. None of us dance during the piece in the traditional sense, but a lot of what Emily does is think about bodies and dynamics: groupings, obsessions, relationships.

Emily has brought an entire vocabulary of movement to the piece which tends to address our topic in oblique and abstract ways. Rather than finding some way for us to act out or dance a response to gun violence, she tends to occupy us with tasks that hint at the emotional and psychological states we inhabit while dealing with it.

Throughout the show, performers are tasked with small back-and-forth foot stomping, which sometimes feels like military marching, at other times like meandering distraction. She pushes us to perform tasks that are exhausting, like jumping repeatedly, primarily for what they authentically produce in our bodies and minds, i.e. not as any literal portrayal of gun-related symbolism.

During a particularly moving section of the piece, eight of us walk in a slowly moving pinwheel around the center of the stage while droning on hand-cranked sirens. There are multiple interpretations of these movements – funeral walk, a beautiful shape, or what?

[line] [line]

[line]

Musicians are usually focused first and foremost on sound. Other visual and theatrical aspects of what we do often fall out as a by-product of this focus. Go to many classical concerts to see how strange this can be. We’re often not aware of how we look, while a great dancer or actor can spend a lifetime figuring out how to walk across a stage. Sometimes, Emily simply asks us to perform a task faster or slower, changing our sense of purpose or intention.

Emily and Ain constantly challenge us to evaluate, and often subvert, the reasons why we move onstage. It would be impossible to overstate the influence of this mindset on how the music comes out in the show.

As for the musical composition process, this is very fluid. I compose the least, tending to focus more on programmatic elements, writing like I’m doing now, and sometimes contributing text. I wrote a few poems during this process that were mostly throw-away, but one line from them stuck out and became a constant element in the show: “Sing when your voice feels faintest.”

Usually a text piece in our shows has been written by Josh, and in A Gun Show he and Ain (who is a brilliant and award-winning playwright) worked intensively on those texts. Jason and Eric wrote the pattern-based percussion pieces, such as the opening drum chorus.

LDJ: You’re performing together but in some ways all maintain individual identities within the piece – there are solo elements, movement elements, and other aspects that are performed or led by individuals. Can you talk about this and how it does or does not represent or correspond with your voices / input into the piece?

AS: Our concept of a chorus originally was meant to hew more closely to the function of a Greek chorus in the great tragedies. We studied a few of them and thought about how this might manifest in our new work. In the end, their function has become more abstract, but it has allowed the five of us to be more individual characters within the drama. A lot of Sō Percussion’s repertoire is about the four of us blending into uniformity, but the 8-member chorus now absorbs that role.

In the last part, I obsessively recite the phrase “well-regulated.” Jason conceived of this piece with my voice and way of intoning rhythm in mind. He knew that I enjoy using my voice, and that I’d also enjoy the task of obsessively layering my recitation on top of itself over and over again.

Jason and Emily have a particularly close relationship when generating new material. They love to get together and try stuff. There are a few moments, such as an early duet, where the two of them move through some sequences that Emily composed. Many of these started as discreet ideas which we then weaved into the show.

Similarly, Josh and Emily wrote independent texts which they merged together into a piece called “squaw wood,” a dark and impressionistic recollection of childhoods spent in the woods and half-remembered experiences with guns.

One element that Ain and Emily get to toy with and take for granted is our established virtuosity as percussionists. We do not always feature it in a traditional way, but it can be pulled out if it fits the conceit. In “gun parts,” Josh wrote for three of us to play on pieces of sniper rifles. The piece is essentially a Sō Percussion piece, with canons and complicated rhythmic elements. Ain directed us to change some of our natural behaviors when performing a piece like this, to make it a bit more regimented visually.

In this way, individual personalities constantly emerge and recede, but the possibility of Sō Percussion members playing complex music together always lingers.

LDJ: How literally has the concept of creating a piece around the loaded question of the GUN influenced the music/composition? Can you paint a more detailed picture for us of the soundscape you’ve created, and what might differentiate the experience of A GUN SHOW in performance vs. other So Percussion pieces? There’s vocal elements, both sung and spoken, marching, and drumming on gun parts, but not exclusively and not throughout the performance — nonetheless in attending rehearsal recently I felt like there were elements of dirge/funereal music, perhaps fife and drum or early military marches, and other nods. Can you talk a little more about this interplay, and your intentions around literal inclusion / allusion / etc?

AS: Many times, literal allusions felt dissonant for us. There are still plenty, but we started to focus our creative process more and more around how the individual and/or collective human is affected by this societal scourge. Most of our political dialogue pits archetypal characters against each other: the gun-toting white rural “patriot,” the inner city gang member, the sensitive and concerned educated urbanite. But the real human truth is MUCH more complicated than the political operatives would have us believe.

One of the constant compositional elements in the piece would be difficult to discern from hearing the piece (even though we explain it in the overhead slides). In the year for which we had most recent data, the number of gun deaths in the United States was 31,513. This number stuck in our imaginations, and many of the percussion pieces in A Gun Show are literal soundings of this pattern. It creates an off-balance meter of 13, which rarely allows us to play in a squarely satisfying groove. We’re constantly kept off-balance, and constantly reminded of this number.

Eric’s opening drum music is quite literal in its evocation of gunfire, especially the canon impact of the bass drums. This music is violent enough and persistent enough to remind you that percussion instruments have this potential.

[line][articlequote]One of the constant compositional elements in the piece would be difficult to discern from hearing the piece (even though we explain it in the overhead slides). In the year for which we had most recent data, the number of gun deaths in the United States was 31,513. This number stuck in our imaginations, and many of the percussion pieces in A Gun Show are literal soundings of this pattern. It creates an off-balance meter of 13, which rarely allows us to play in a squarely satisfying groove. We’re constantly kept off-balance, and constantly reminded of this number.[/articlequote][line]

Some of the music symbolically represents an issue that orbits around gun culture. Several times throughout the show, our chorus sings the iconic blues chord progression (I, IV, I, V, IV, I). This is a nod to the fact that gun culture in America is inescapably tied to its history of oppression through enslavement. The weary hopefulness of Afro-American diaspora music has had a profound influence on us, although we try very hard to be respectful and not appropriative of that influence.

Here it’s worth mentioning that the symbolism of the drum gets very richly complicated. I wrote above that percussion instruments were often invented to facilitate violence, which is true. But in America (and now really the world), those same instruments like the snare drum and cymbals are most closely associated with one of the great American instruments, the drumset. Black musicians played a singularly important role in adapting these instruments from their purpose of violence to one of joy, expression, even ecstasy. To watch a drummer like Tony Williams, Philly Jo Jones, or Max Roach, one can only think of flow, creativity, and inspiration. Growing up as a drummer, we worshipped these black performers, and to be a percussionist in the USA is to be profoundly affected by this tradition.

We cannot ignore that two of the primary social movements of our time – gun control and black lives matter – are intimately intertwined. In our opinion, one of the frustrating blind spots of the gun issue is when white proponents of gun rights refuse to acknowledge that guns have been the primary tool of oppression against people of color. They reduce this thorny history to “guns don’t kill people,” as if there’s no significance whatsoever to the power that widespread gun usage exerts in social hierarchies.

LDJ: Now we get perhaps to the stickier stuff – let’s talk about the social and community potential / intentions of this piece.

For a little background – you’re all educators, directly, running the institute and doing substantial work in schools – am I missing anything? Has there always been a didactic element of what you do as musicians? How has that part of your work evolved individually and/or as an ensemble?

AS: Yes, it has always been a part of what we do. I actually always imagined I’d be a teacher, partially because it seemed one of the only avenues open for doing what I wanted to do. Many gigs and residencies in the classical circuit expect and require you to do teaching, whether as community outreach or university classes.

We currently have a very heavy teaching load: we are the ensemble in residence at Princeton University, we run the percussion department at the Bard Conservatory of Music, and we have our Summer Institute and teaching that is tied to touring.

What we’ve found is that we’re all as passionate about teaching as we are performing. If you gave me ten million dollars right now, I’d definitely take more vacations, but I wouldn’t stop teaching.

As co-teachers we’ve slowly learned how to lean on each others’ strengths. Percussion is a vast subject, and any one teacher can only facilitate all the different kinds of learning that might be involved. The four of us work together constantly to provide the best instruction we can.

LDJ: What’s SP’s general position on public education and community engagement via the creative arts? Do social issues inform your work with any frequency? Beyond the sort of standard post-show talk-back or Q&A, either individually or as an ensemble have you sought to engage in public dialogue about particular issues or conflicts via particular compositions or performances in the past?

AS: We’ve never tackled a social issue like this directly. By and large, we do not see ourselves as an issue-based artistic collective. There was something shattering and infuriating about Sandy Hook that just tipped us over into wanting to deal with this subject.

[line][articlequote]…our opening drum piece is much more evocative of war than it is of a mass shooting or some other domestic conflict. The bass drums sound like cannons, and by opening with that piece I think we remind people that the overall militarization of a society has consequences for its domestic life. We see now that US police departments often resemble SEAL strike teams more than constables. Eisenhower warned us that permanent militarization would produce this….the role of the gun in contemporary life is our main concern, without losing sight of the gun as a historical tool as well.[/articlequote][line]

LDJ: Though the initial impetus was gun violence and gun control, in the US specifically, does this mean that questions as to militarization and war, import and export of weapons, etc, beyond the US borders, whether in relationship to the US as a major exporter of weapons (and of wars), is also part of the story? Since its non-us military weapon pieces that are being used as percussive elements, there is already a nod to that. Would you say that, in general, the main topic is the role of the GUN in contemporary US life? Human life? Media? History?

AS: This is undoubtedly part of the story. I think our opening drum piece is much more evocative of war than it is of a mass shooting or some other domestic conflict. The bass drums sound like cannons, and by opening with that piece I think we remind people that the overall militarization of a society has consequences for its domestic life. We see now that US police departments often resemble SEAL strike teams more than constables. Eisenhower warned us that permanent militarization would produce this.

I would say that our focus is really the USA. The Russian sniper rifle was chosen more for its availability than for its provenance. But yes, the role of the gun in contemporary life is our main concern, without losing sight of the gun as a historical tool as well.

LDJ: Whose voices have been considered in the process of putting together the piece so far? (ie, whether specific people or specific groups of people / interest groups / books, etc). What has the research process consisted of to date? I know we’ve spoken a lot about the potential crowdsourcing of stories from various communities in relationship to putting the book together.

AS: At the moment, two distinct paths are emerging: what’s in the hour-long show itself, and what else we’re planning to gather/solicit/put out there. In the show, we endeavor to constantly speak with voices that we know and experiences we’ve had. This means that Emily or Josh’s background of growing up in rural areas where guns are commonplace is reflected in the show, but stories about what life is like in gun-saturated minority urban areas is not.

A lot of the research has been focused around the statistics of gun violence and the political conversation. Our main protest is against the binary and oversimplified nature of the dialogue around the issue.

We’ve also immersed ourselves by visiting a shooting range and spending some time with rural hunters in Vermont. Our primary interest has been in trying to understand the perspective of people who want gun rights to be protected. What we’ve mostly found is that the vast majority of gun enthusiasts are reasonable people who wouldn’t have a problem in principle with some basic controls and regulations. But the NRA plays a zero sum game with them, telling them you’re either all in or you’re out. [line]

[line] We are working on several supplementary activities right now (including this dialogue with you) that will make room for a broader and more diverse collection of voices that could flow into our project.

LDJ: We’ve spoken at some length about A GUN SHOW’s desire to not be a singular statement on gun control or gun violence, so perhaps it’s most accurate to describe it as more of a meditation around the role of the gun in our lives both actively and in our imaginary. If A GUN SHOW needn’t have an agenda, or an answer, where is the line drawn in terms of ENOUGH? Ie: how does one determine what is essential to include, or ok to leave out?

AS: This has been an active conversation among our collaborators. We spent a fair amount of time thinking about what we wanted to avoid – misrepresenting or appropriating voices of people of color, exploiting the suffering of gun victims for the sake of an artistic statement, etc – and now we’re thinking more about what we want to stand for.

We’ve all agreed that we can’t be completely agnostic, as much as we want to make room for multiple sides of the issue. In that spirit, we believe that we can sum up what we stand for by saying “sensible gun regulation now,” and “black lives matter.”

The last section of the work is about 500 utterances of the phrase “well-regulated,” so the show is not truly agenda-less. What we fervently want is to be able to have an aesthetic experience and a conversation that doesn’t immediately retreat to the pre-scripted corners of identity and partisan bickering that usually defines it.

LDJ: When I work with performers or visual artists on documenting their work, they often find that the act of considering writing in tandem to the performance or art itself shifts the burden somewhat away from the work vis-a-vis its responsibility in concretely carrying the social message. You’re already a writer who considers your work via language as a personal practice. Have you found that this is the case with A GUN SHOW? We’ve been talking about a book / documentation in tandem for some time, and you’ve always planned on some additional materials. Tell us more about where and how you’ve decided to speak directly to the issues and where you’ve allowed it to be more sensory / experiential, and how you found (or are continuing to find) this balance.

AS: As I mentioned previously, I think art is much better at dealing with humanity than with a specific issue. The universal experience of suffering, fear, and hope are not just about gun issues, but they can be magnificently conveyed in a work of art.

It has been enormously helpful to me to think about a multi-pronged way of dealing with this project, where I can articulate thoughts and ideas to you in a more concrete way, while our staged work deals with the cracks and corners of human experience.

LDJ: What are your hopes for this piece, both in its upcoming performances and beyond? What sort of impact or potential positive conversations might it generate? Would it be something you’d like to see other professional or school ensembles performing and using to encourage dialogue in their own communities?

AS: I hope we get more opportunities to do it (several are already booked as of this writing). We’ve already had many positive conversations around showings of the work. Along the way, even people we know well have shared stories with us about a suicide or other gun-related impact on their life. The ubiquitous nature of guns in our society is not always felt on the surface, but it’s there in surprising quantities that we don’t always talk about.

I cannot imagine this being a repertory piece for anybody but us. So much of the storytelling and movement is meant for our own bodies and voices.

LDJ: Could and should this piece continue to evolve and change in response to the continuously fraught story of guns in this country and worldwide? If others wanted to perform this piece but customize it in some way, including their own stories and images, would you be open to that? Is there flexibility in the piece for continued growth and adaptation?

AS: It certainly could, but I’d say that we’ve been honing it relentlessly, so that it doesn’t feel like a modular piece. (Our last show “Where (we) Live” was explicitly modular).

I shouldn’t say now that there’s no way others could do it, but I can’t currently imagine that.

[line][articlequote]Our guiding principal, which I think is a good one when making art, is to listen to our own inner voices and consciences. On some level, we just wanted people to be in a room together where they can feel some sense of humanity and connection to each other over this issue. The overriding emotions conveyed by the media are fear, suspicion, and rage. I think music and theater have great potential to open up such a space.[/articlequote][line]

LDJ: Do you feel that this piece can help us begin to heal and work together? What audiences do you feel would most benefit from this piece and discussion around it? Is it possible that by including music in the conversation, we are accessing subconscious emotional spaces of connection around our human experiences of fear and anxiety, care for loved ones, a desire for safety, etc? Have you intentionally worked with the emotional landscape of the piece in considering audience reaction and potential affect?

AS: I really don’t know what it can or can’t do. Our guiding principal, which I think is a good one when making art, is to listen to our own inner voices and consciences. On some level, we just wanted people to be in a room together where they can feel some sense of humanity and connection to each other over this issue. The overriding emotions conveyed by the media are fear, suspicion, and rage. I think music and theater have great potential to open up such a space.

A lot of our most intensive honing of the piece has to do with feedback we’ve gotten from audiences. This is a very delicate place to tread, and any muddled intentions or mis-read cues can backfire in conveying what you want to. We’ve worked hard on the emotional experience. I’d sum it up as communal, contemplative, and sometimes challenging. But we work really hard to not make the audience feel alienated. That matters to us a great deal.

LDJ: What are your next steps, for future projects? Do you feel a growing commitment to create work that speaks to major subjects in the social imaginary? Has (and how has) working on this project shifted your consciousness about the role of performers / composers in community dialogue and healing?

It’s funny, we’ve just finished another project in parallel to this in the Northeast of England. Called “From Out a Darker Sea,” it’s a meditation on the people and landscape of that historical industrial area, formerly full of coal mines and shipyards.

In this particular piece, our last movement memorializes a young man who died an accidental and senseless death down in the mines 30 years ago. Some of his comrades from the pits were at our show, and the emotion on their faces made it evident that the incident still felt like yesterday to them. There really was no need to have any conversation about whether our contemporary practices were accessible, because there was something deeper and more immediate that spoke to their aesthetic experience.

Working on A Gun Show has given us confidence to meet social complexities head on through our art, and our other project was immeasurably helped by that process.

LDJ: Do you feel in general, as a performer and therefore someone commanding public attention, that you have a responsibility to the public to at least engage with and/or to take clear political and social stances on issues? Is it enough to just perform and teach the arts without clear relationship to / engagement with art and creativity’s (historic and potential, continued) role in activism and social justice/change?

AS: I and we are still grappling with this. Our mission as an organization is generally not geared towards political advocacy, hence my long and slow process of deciding where to draw the line on gun politics. I do think that teaching and making art/music/theater can be helpful in this regard even if your work isn’t specifically political. Values like diversity and inclusiveness are moving to the forefront of our concerns as a group, and that’s where I think we’ll see the most activity in the near future.

[line][line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/adam-300×300.jpg[/textwrap_image]Adam Sliwinski has built a dynamic career of creative collaboration as percussionist, pianist, conductor, teacher, and writer. He specializes in bringing composers, performers, and other artists together to create exciting new work. A member of the ensemble Sō Percussion (proclaimed as “brilliant” and “consistently impressive” by the New York Times) since 2002, Adam has performed at venues as diverse as Carnegie Hall, The Bonnaroo Festival, Disney Concert Hall with the LA Philharmonic, and everything in between. Sō Percussion has also toured extensively around the world, including multiple featured performances at the Barbican Centre in London, and tours to France, Germany, The Netherlands, South America, Australia, and Russia.

Adam has been praised as a soloist by the New York Times for his “shapely, thoughtfully nuanced account” of David Lang’s marimba piece String of Pearls. He has performed as a percussionist many times with the International Contemporary Ensemble, founded by classmates from Oberlin. Though he trained primarily as a percussionist, Adam’s first major solo album, out on New Amsterdam records in 2015, is a collection of etudes called Nostalgic Synchronic for the Prepared Digital Piano, an invention of Princeton colleague Dan Trueman (who collaborated on There Might Be Others) with Rebecca Lazier for The OS in Spring of 2016. In recent years, Adam’s collaborations have grown to include conducting. He has conducted over a dozen world premieres with the International Contemporary Ensemble, including residencies at Harvard, Columbia, and NYU. In 2014, ECM Records released the live recording of the premiere of Vijay Iyer’s Radhe Radhe with Adam conducting.

Adam writes about music on his blog. He has also contributed a series of articles to newmusicbox.org, and the forthcoming Cambridge Companion to Percussion from Cambridge University press will feature his chapter “Lost and Found: Percussion Chamber Music and the Modern Age.”

Adam is co-director of the Sō Percussion Summer Institute, an annual intensive course on the campus of Princeton University for college-aged percussionists. He is also co-director of the percussion program at the Bard College Conservatory of Music, and has taught percussion both in masterclass and privately at more than 80 conservatories and universities in the USA and internationally. Along with his colleagues in Sō Percussion, Adam is Edward T. Cone performer-in-residence at Princeton University. He received his Doctor of Musical Arts and his Masters degrees at Yale with marimba soloist Robert van Sice, and his Bachelors at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music with Michael Rosen.

Check out Adam’s blog about music.

[line][line]

[box]

Adam has said that: “The Operating System has been an incredibly valuable resource and outlet for me and for Sō Percussion. Although writing is not my primary craft, I love to do it, and Lynne facilitaties communication and writing about music in a way that makes it feel perfectly seamless and natural. There are times when I need to go way deeper than a standard interview or boilerplate explanation of what Sō Percussion does. Lynne gets to that point wickedly fast, so that I can move straight into my most developed thoughts about what we are trying to do artistically. Independent projects like The Operating System have the potential to transform the way different art forms speak to each other and bring many vital voices to the forefront. Supporting and funding this project will help us all to crawl out of our creative tunnels and speak more fruitfully together.” – Adam Sliwinski, Sō Percussion

Our crowdfunding campaign is currently underway – won’t you help us do this important work with a donation today?

[/box]

[line][line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]