[re:con]versations :: OF SOUND MIND :: Process and Practice with Everybody's Automat's Mark Gurarie

[line]

[box]

[quote] In 2016 The Operating System initiated the project of publishing print documents from musicians and composers, beginning with Everybody’s Automat and this year’s chapbook series, all of which fall under the OF SOUND MIND moniker, and all of which are written by creative practitioners who work in both poetry and music. I asked each of them a series of questions about the balance of these two disciplines in their practice, which I’ll share with you here.

Please consider this template, approaching The OS’s key concerns of personal and professional practice/process analysis combined with questions of social and cultural responsibility, as an Open Source document — questions to ask yourselves or others about process and the role of poetry today.

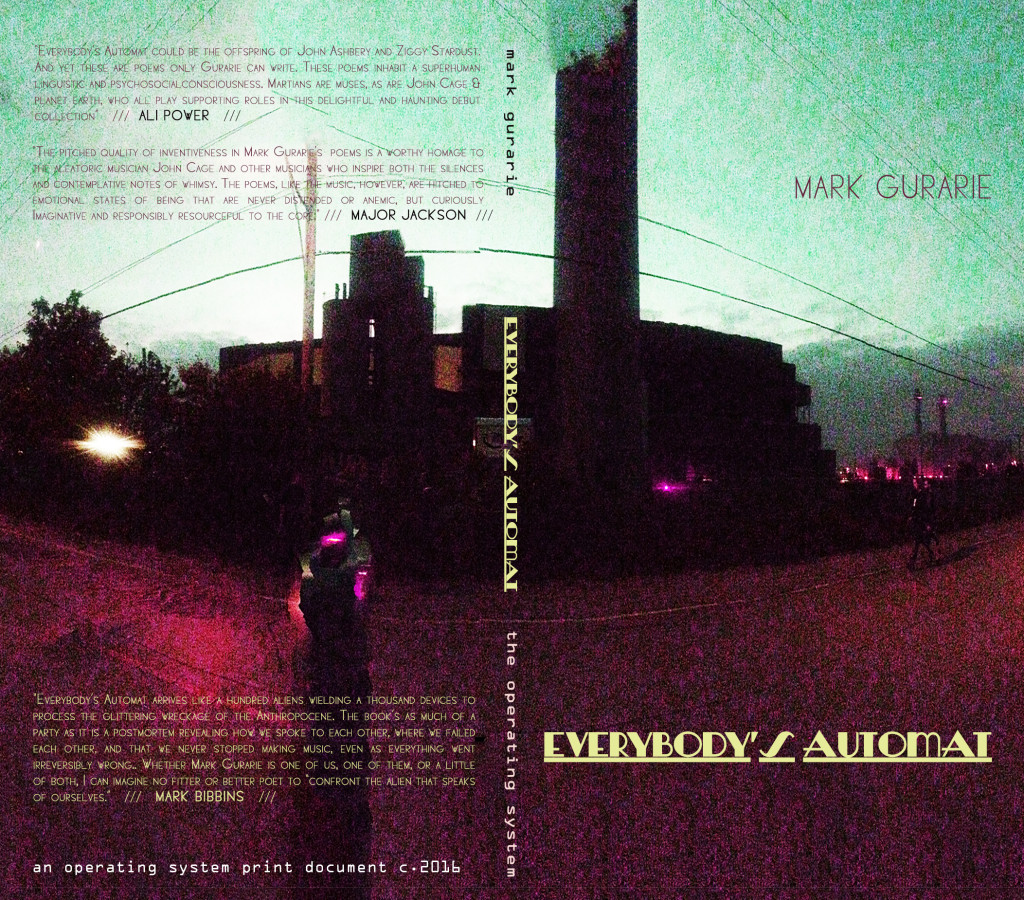

In this conversation, I talk to Mark Gurarie about his work and his debut volume on The OS Press, Everybody’s Automat.

– Series Editor / OS Managing Editor Lynne DeSilva-Johnson [/quote]

[/box]

[line][line]

[articlequote] A big ‘theme’ that I hope to convey in Everybody’s Automat is that of the strange utopianism, the resoluteness and ultimate failure of the 20th century; the book both idealizes and reels in horror of the cold war, capitalism and industrial process, as well as the ways in which the monochromatic aesthetic of the previous century—its hopes and dreams—fell to pieces and brought us here. Since the work is composed of discrete entities, I imagined them as sort of like slots in an abandoned automat lunch joint. The machinery is rusty and far removed from its original glossy and futuristic facade, but the plastic-wrapped Wonderbread sandwiches, chock-full of preservatives, might still be edible 60 some years on. Each section costs approximately 5 cents.” – Mark Gurarie [/articlequote]

[line][line]

Who are you?

I’m a poet, writer, teacher, editor and rock “musician.”

Why are you a poet?

I’m a poet because I enjoy exploring what is possible in language, and the multifarious ways in which it can work. I like sort of chewing on words and collections of words; I savor the often disordered progression of thought that comes from an active mind, or is imprinted in it from the surrounding environment, or might suddenly appear as a means to memory. Especially in this day and age, we live surrounded by a constant influx of language—be it from reading books, from broadcasts, from the endless texts of the internet or just the chaos of the every day—so poetry becomes a way of tuning into specific frequencies within this array. It might also be a means to come into dialogue with disorder, while speaking to those parts of the psyche that create order; it’s something that is always in that liminal zone between sense and nonsense. I’m a poet because I appreciate the musical qualities of language as much as I appreciate the ways in which language might be able to convey ideas that do not fit into prose. In a sense, then, poetry is what I feel to be the most natural expression of my thoughts; I feel comfortable within its simultaneously freeing and restrictive idiom.

When did you decide you were a poet (and/or: do you feel comfortable calling yourself a poet, what other titles or affiliations do you prefer/feel are more accurate)?

I know that by the time I was in late high school, perhaps around the age of 17, I knew that I wanted to be a writer of some sort; up to that point, I focused primarily on visual art while playing bass in a band. It was not until I was 20 that I realized that poetry was to be my focus; I can’t quite pinpoint it, but I began writing stream-of-consciousness inflected prose poems in the manner of the beats, whom, of course, as a young white dude in college, I came to admire. I appreciated the lawlessness of it all—the radical spirit in the poems and the way that their form challenged convention—so I decided at that time to take it on by, well, writing poems.

What’s a “poet”, anyway? What is the role of the poet today?

This is a tough question because in the US, poetry is relegated to the margins of cultural and social production; whereas in many

other countries and cultures, poetry is more central. Here, outside of exciting popular developments like the emergence of slam and spoken word—and I actually think you might be able to include the vibrancy of hip-hop here—poetry is famously ignored by non-poets. That said, American poets have a special position as being the voice of the exterior, the underbelly, even if their exhile from whatever the “mainstream” might largely be self-imposed. In this sense, then, poets are able to use their craft to move in a freeer way than many of their artistic peers who are more closely attuned to the market, and furthermore, the relationship between poet and broader American society is always evolving.

As much as can be said about the disengagement of say, modernist poets in the early 20th century, from political or social discourse, you have strains that speak for under-represented voices, that lift the mirror to society at large, like those of the Harlem Rennaissance, for instance. In a similar way, the poet today has the opportunity to employ the craft to explore and challenge the status quo, and in that, to bear witness. To me, it’s incredibly exciting that Claudia Rankine’s Citizen was actually on the NYT’s best-sellers list (two different times, I believe), or that Patricia Lockwood’s “Rape Joke” went viral.

In its own way, and occasionally, the culture at large looks to the poets and lets them in; the onus is on the poets to use their craft and their perspective to make work that is meaningful, challenging and makes a genuine attempt to capture an underlying truth.

[line]

What do you see as your cultural and social role (in the poetry community and beyond)?

[articlequote]The poetry community is a sprawling and often dysfunctional family, but at the core of it, anyone that reads it or that goes to a reading becomes a member. As much as there are genuine and heated debates about how it functions, what it does and what it should do, it’s important to remember that poetry can only live when it is written and when it is read and when it is loved. In this sense, I view my position as a poet as one of a facilitator and champion for the voices I see as doing good work. This is why I was for a long time involved in curating a reading series, and it’s why I write reviews and work (well, volunteer) as an editor of them. In this, I like to think that I am helping create some more space for the art in the wider sphere, while letting it continue to grow and develop. Furthermore, every poem out there is in dialogue with the poetry that preceded it; in this sense, too, my own work serves the function of furthuring this important conversation. [/articlequote]

[line]

Talk about the process or instinct to move these poems (or your work in general) as independent entities into a body of work. How and why did this happen? Have you had this intention for a while? What encouraged and/or confounded this (or a book, in general) coming together? Was it a struggle?

While the manuscript as a whole wasn’t in my mind, as such, when these poems were written, it should be noted that the sections within it represent discrete, if in many ways related, entities. The first and last sections—the two most directly concerned with exploring music—existed previously as a chapbook, Pop :: Song and were conceived to sort of counterbalance each other. The first is an exploration of experiment in musical forms through an ekphrastic response to 20th Century composer/troublemakers, Erik Satie and John Cage, and the latter is composed in the form of a pop song and looks at the ways popular music can be equal parts provocative, evocative and sentimental. The other two sections also hang together tightly. One is a series of poems in the voice of an alien who has mislearned the language through broken 20th century broadcasts, and in the other the urban contemporary and the natural is exposed as a mutually idealizing false binary.

I found, though, in looking at the poems over the years that they resonated with each other; they had similar investment in musical approaches, fractured lexicons and indirect approaches to shared, cultural memory as well as the personal. It should be noted, too, that these come from a two to three year historical period for me; though not my original intention to have them be some sort of “recording” of my life and my art, they became just that. Over the course of piecing together the manuscript, I did encounter struggles and doubts; particularly, it took me a while to accept that the sections really should be in their own “rooms.” It was jarring for me that this was not looking like a more traditional collection of poems, but a kind of nesting doll or some sort of toy composed of differently shaped pieces. Eventually, though, I relaxed, and, as the old trope goes, let the work guide me. I had to have faith in the original vision(s).

Did you envision this collection as a collection or understand your process as writing specifically around a theme while the poems themselves were being written? How or how not?

As mentioned above, it was easier to conceptualize each of the sections as thier own “collections,” and I think that it was really in retrospect that I realized that they broached similar thematic territory, if from different angles and approaches. Ultimately, these poems reflect the concerns I had at the time—and probably to a great extent still do—and the types of things I was doing in them mirrored each other. If anything really binds them, come to think of it, it is that they are all sort of top-down in construction. I developed a concept or idea, most likely after a few were written, and used that to guide the generation of the rest of them. It is very often a way that I work; I’ll land on an idiom, structure or form, and try to work it out in as many ways as I can without losing my mind.

Speaking of monikers, what does your title represent? How was it generated? Talk about the way you titled the book, and how your process of naming (poems, sections, etc) influences you and/or colors your work specifically.

A big “theme” that I hope to convey in Everybody’s Automat is that of the strange utopianism, the resoluteness and ultimate failure of the 20th century; the book both idealizes and reels in horror of the cold war, capitalism and industrial process, as well as the ways in which the monochromatic aesthetic of the previous century—its hopes and dreams—fell to pieces and brought us here. Since the work is composed of discrete entities, I imagined them as sort of like slots in an abandoned automat lunch joint. The machinery is rusty and far removed from its original glossy and futuristic facade, but the plastic-wrapped Wonderbread sandwiches, chock-full of preservatives, might still be edible 60 some years on. Each section costs approximately 5 cents.

I do love titles, and, since, as mentioned above, many of these poems were generated with a ruling concept in mind, the titles have a massive influence on the works themselves. This isn’t always how I work, but what is nice about working in this way is that it allows the poems in question to develop a life of their own and to surprise me. When that is happening, in my view, you are doing something right.

Of course, also, the title Everybody’s Automat is a riff off of Stein’s Everybody’s Autobiography, and must therefore be in dialogue with her fractured, self-conscious-without-a-self approach to memoir. As much as, at the time, I would’ve told you that these poems are not autobiographical in any sense, there was indeed a “there there” because my own history as the child of Ukrainian immigrants, as a kid invested in punk music and modern art, as an urbanite in fake deer skin, as a budding artist, is in there. It took some years for me realize that; as much as I tried not to be a self-referential, self-absorbed artist, I of course was.

What does this particular collection of poems represent to you

…as indicative of your method/creative practice?

…as indicative of your history?

…as indicative of your mission/intentions/hopes/plans?

These poems certainly encapsulate a particular period in my creative practice, one during which I was invested in formal experiment as a means to indirectly present autobiography, history, social critique and linguistic play. I was excited, at the time, by the possibilities that collage, translation, mistranslation and a focus on the musical aspects of language can bring to the lyric form. This is perhaps best seen in the “Resistant Is Futile” section, in which, in keeping with the imagined lexicon of an alien and how it might develop a concept of Earthly life through broadcasts, lines repeat or are slightly distorted. To create this effect, I sometimes used translation engines to fracture the meaning of some phrases, and I got to pun with abandon. Eventually, the persona of this possibly malignant being overtook, though it is likely also, in many respects, a reflection of the russian accented English of my parents. In crafting them, as well as the other sections, I became excited by the possibilities of experimental approaches to writing practice, and I exhuberantly took these on. I learned a great deal in working with these poems, especially in the editing process, and many of the methodologies still crop up in my current practice.

What formal structures or other constrictive practices (if any) do you use in the creation of your work? Have certain teachers or instructive environments, or readings/writings of other creative people (poets or others) informed the way you work/write?

The poems here are certainly indebted to both received and invented forms and practices. At the core of it, they, and I think much of my work, play with notions of translation as this concept is taken on by writers like Anne Carson and Caroline Bergvall. Carson’s Nox, in particular, was influential; I was struck by the way that the act of translating a Catullus poem became her means of coping with the loss of her estranged brother to create a book that, in many respects, is so much more than “just” poetry. I got enamored with the idea that every creative act is, in essence, a form of translation; the translation of feeling and thoughts into certain forms; the translation of real-time musical moments into texts, and the extent to which mistranslations and mistakes are as integral as anything else. Everyone, it might be said, has their own personal language; therefore, every piece of writing or music is an attempt to translate this to something for the broader world.

The first and last sections are in direct dialogue with musical approaches; I was reading a great deal of John Cage, for instance, and became invested in his ideas about aleotoric and experimental practice. In some sections of “Pop : Poem Manufactured in the Furniture Music,” Cage’s lines intermingle with mine and provide shape to the poems. It should be noted, too, that the concept of “Furniture Music,” comes from Satie, who invisaged some of his pieces as being more ambient, something specifically to be background music. I tried to echo the sense of experiment that guided these composers, translating what I learned from them into the serial poem. Similarly, in the final section, “: Song: Poem to be read in 3:18,” I adopted the rigid structure of the pop song: intro, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, verse, coda. Here I was essentially translating the panoply of emotional and visceral reactions to the rock and punk songs I love (and hate).

The second section, “Sentimental Animals,” I view as musical in its approach; there is no rigid form to speak of, but I wanted it to have its own lexicon, and, in particular, to play off the ways that meaning and “sentiment” can be influenced by context. Certainly, also, these poems are intended to interrogate notions of urbanity and contemporary existence, at least in certain circles, as both separate from and idealizing the natural. Because of a variety of factors, we live in an era in which urban spaces like Brooklyn have been colonized by those enamored with a close connection to the land—you know, “farm-to-table,” and “rustic” in aesthetic looks—while being part of a demographic ecology that preys on and pushes out what the borough traditionally was. The nostalgia for authenticity, in the end, is what both drives development and preys on the local.

Perhaps most conspicuously, the “Resistant Is Futile” section is indebted to the exploded notion of the sonnet a la Ted Berrigan. Here texts are mixed and remixed: starting from material that comes from corporate speech, advertising and popular entertainment, I freely distorted, collaged and ran lines through translation engines to give it all that “extra-terrestrial” feel. I like the notion that all of our telecasts and broadcasts radiate endlessly into space and are being received by others that are out there, and further, that these frequencies are how extraterrestrials might form an understanding of the human race. The work certainly has roots in my reading of LANGUAGE poetry; they play with the inherently ideological and political sense of language as seen in corporate speech and pop culture. They are also my approach to both persona, a la David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust, and the kind of surrealistic cosmology you find in Sun Ra or Parliament Funkadelic albums.

[line]

[articlequote]As far as live performance, I don’t mean to be cliché here, but that is my drug or even my religion. When playing with my band or other musicians—when several players are locked in together and talking to each other in that ‘jazz’ sense—there is simply nothing like it. The sum is greater than the parts and it’s truly revelatory. I don’t have religion—I am through and through an atheist—but I’ve felt religious (or perhaps the term ought to be ‘spiritual’) experiences while performing. If you can truly connect with your audience, if you have their attention in that moment of time, it is zen, it is ecstasy, it is flow, and it is, above all, a communal and shared experience. I may never be a professional performer, there may not be stadiums in my future, but I will likely always be addicted to the stage. [/articlequote]

[line]

Talk about the specific headspace of being a musician / composer / performer – when and how do you feel you enter a space of consciousness in which “sound” or “music” is the dominant sense?

In contrast to writing text, which for me can be a much more deliberate and painstaking process, I feel that when I am writing songs or playing music, there is a much more “natural” and intuitive feel that takes place. While I can read music and have some understanding of theory, I approach playing from a more instinctual space; I hate jam band music, but I am, at the heart, a jammer. This is likely because I have developed most as a musician from the perspective of the blues idiom, in the sense that I am most accomplished at playing “rock” bass. Though I was lucky enough to have had some violin and piano lessons as a kid, it wasn’t until I owned a guitar and had to play bass in my friend’s band (at the age of 13) that I felt in any way competent. I guess it has to do with the fact that, at the core of it, music is more closely aligned to math and physics; there are principles that determine harmonies, that dictate dissonance, that determine the frequency and rate of distortion. And yet, it’s not analytical: You don’t need to speak any language or to have read any books to “get” music.

I am not nearly as prolific a songwriter as I am a writer of poetry or prose, but when I do it, I actually feel much more relaxed. Since songs work within real time, there is, at least for me, less fretting about small decisions. So, for instance, I like writing lyrics because, in many ways, it is so much less stressful than writing poems; sure you can flip amazing things with them—express a great deal in a literary sense—but you can also be as effective singing ‘ooh’ and ‘aah.’ Sometimes, while walking, I feel I can tune into rhythms, melodies and harmonies very sharply and distinctly—be they compositions of my own or ear worms—in a very sudden and direct way. It’s that old feeling, I guess, overtaking me. This makes sense because music more so than text, in my opinion, taps into the body and works in a non-logical or semantic way.

As far as live performance, I don’t mean to be cliché here, but that is my drug or even my religion. When playing with my band or other musicians—when several players are locked in together and talking to each other in that ‘jazz’ sense—there is simply nothing like it. The sum is greater than the parts and it’s truly revelatory. I don’t have religion—I am through and through an atheist—but I’ve felt religious (or perhaps the term ought to be ‘spiritual’) experiences while performing. If you can truly connect with your audience, if you have their attention in that moment of time, it is zen, it is ecstasy, it is flow, and it is, above all, a communal and shared experience. I may never be a professional performer, there may not be stadiums in my future, but I will likely always be addicted to the stage.

Do you consider yourself equally musician/composer/poet? Are there other equally important disciplines, influences, labels or other words you’d want to call our attention to that we might not know that you feel are important in understanding your creative practice?

I wouldn’t say I am more a poet or a musician, so much that I like to think my sense of one informs the other. That said, while I am a capable musician (decent bass player, so so on the guitar), I probably feel more confidence in my use of language and words. I can’t hang with classical players, with jazz cats, with those folks that spend and have spent hours a day practicing, but I can play by ear, write bass lines, think of and play chord progressions, structure songs, think of harmonies and that sort of thing. Maybe just maybe this simplification could be true: I approach writing like a musician, and music like a writer. Well, maybe not.

I can say that a very formative experience for me as musician, poet and performer was my time spent doing spoken word in San Francisco and collaborating with individual or small ensembles of musicians. Back in 2003, I became involved in an arts collective called the Collaborative Arts Insurgency or the C.A.I. (for the record, I never loved the name, but I did like the acronym), which organized guerilla style open mics at the 16th and Mission BART stop plaza on Thursday evenings. There was no sign up and no mic; you just sort of went up and did one piece at a time before ceding the “stage.” The collective itself was rather short-lived (too many divergent ideas, colliding egos and disparate agendas), but it’s pretty neat that, to this day, that plaza plays host to poetry open mics on Thursdays.

Anyway, while the collective was running, a core of musicians and poets emerged—of which I became a part—and we began to put on variety type shows in performance spaces in the Bay Area. Our thinking was that poetry and art needed to be public, needed to be pulled out of the academy and brought to the “people,” and we also really believed in the power of dialogue between different art forms. Anyway, I “cut my teeth” there, every Thursday, out in the street, shouting poems that I memorized to my peers, strangers, passersby, stragglers, drug addicts and audience regulars. This eventually lead to my working with extremely talented collaborators in the creation of spoken word/music pieces, some of which we even recorded, and with which we even did a tiny scale tour (by tour, I guess I mean like three gigs in Portland, but still!). More so than any previous band experience I had, I felt that performance high there. Even though it gave me a bad case of “Spoken Word Voice,” (I was 23, I was idealistic, I was pretentiously anti-pretension, youth!) it also influenced the way I thought about poetry as it relates to real time. I also would occasionally play some bass for others, and it was there that I first learned to vocalize while playing.

But so what I got from that was a couple things: I wanted on the one hand to make work that could impact a wider range of people, but also I wanted to challenge the form and be respected as an artist by the community. I think that this is why, these days, I play music and write songs in an indie-rock/punk/what-have-you band as a ‘popular’ outlet and also am a poet in a more “academic” sense. There’s no denying that music impacts more people than poetry; it is simply more democratic in the way it works. At any rate, I like to think I bring musical intuitive strategies into poems, and I like to think that my poetics help with lyric work.

Describe in more detail the relationship between music and language in your life and practice. How and when are these discrete influences / practices and how/when are they interconnected? How do they influence each other? Do they ever not?

In terms of your written or text based work, do you “hear” it, speak it out, hear its rhythms, before you write or as you write and/or before you perform? Do you ever memorize your texts / treat them more like a score or sheet music?

So first of all, as any editor or teacher will tell you, you absolutely must read written work aloud to edit it, and for my poetry practice—as with I assume most all poets—the editing phase is the most vital. I tell my students that this helps place you into the head of your reader, so it’s absolutely essential to the process of going from rough ideas to finished product. I don’t know if there is a set way that I write poems, but sometimes certain lines will be “heard” to me before they are written down; as with some songs I’ve written, I tend to think clearest when I am walking, and I’d venture to guess that I’ve composed some of my best work en route somewhere and was likely only able to scribble down a tiny piece of it retrospectively.

As I mentioned above, I used to make it a point to memorize poems I would “perform” when I was younger and more involved with what people call “spoken word.” It was, to the 23 year old me, a point of pride that I didn’t need a page, and I liked the idea—likely stolen from musicians—that every time you performed a poem, you were rewriting it in that space of real time. Of course, that snotty nosed kid I was then would likely think the person I am now, some 13 years later, is a lame, academic sell-out, in that I read from pages, and I have one of those expensive MFAs.

I don’t often read poems these days—perhaps an “always the bridesmaid, never the bride” type effect from having been a reading series host and curator for so long and not, like, actively trying to get myself booked—but when I do, even though I don’t memorize the poems, I practice them and I time them. Bring on the rant about how too many brilliant poets out there simply do not know how to read their work aloud or use a microphone, to their detriment. Poems on the page, when read aloud, are indeed a kind of score to me; they have the words, they might suggest how they are to be presented through line breaks/punctuation/spaces, but, like a violinist interpreting a written piece of music, it’s up to the reader in the moment to give it life (or to be Biblical about it, to breathe life into it).

I am sometimes tempted to try and memorize poems I write these days, but I think a good deal of that impetus is subsumed by the singing I do in the band. Frankly, I also feel that I don’t have the time to do it; I want to move on to the next thing. It’s just not as important to me these days, necessarily, to read poems to audiences of strangers (which isn’t to say that I don’t enjoy it). Still, when I see poets do that, it is always so striking; if you can recite your work while staring into someone’s eyes, it’s a certain kind of spell you’re casting. Some might argue that this is cheap or for effect—maybe sometimes it is—but it can also be amazingly engaging.

I should add, too, specifically with this book, that I recorded one of the sections, “Resistant Is Futile” in collaboration with the brilliant cellist and composer Eric Stephenson. [Ed: listen via soundcloud, above.] These poems, being in the voice of an invading alien that has not quite learned the language properly, lent themselves to performance, quite naturally, and essentially became a kind of score for a body of recorded work. Using studio techniques, synthesizers, live instruments, basically everything that current technologies allow in terms of audio-manipulation, we were able to create a truly extra-terrestrial space to package these pieces in. We initially recorded the words “dry,” that is without any bells and whistles, and then went back through them and turned them into what they became: very, very strange and haunting. In terms of this recorded body of work, I happily ceded much authority to Eric, allowing him to respond to the material through his idiom and his art. He is not only classically trained, but has an interest in a huge range of jazz, classical and popular musical forms; you could be as easily wowed by his cello playing, his arranging and his ability to rock Ableton Live, effects pedals and a Midi-keyboard. What would take me 45 takes to get right, he’d nail in one. At any rate, it was fascinating to bring the words on the page essentially “back” to life—to interpret them as a score quite literally—and to treat them as I imagined them to be: broken broadcasts from innerspace/outerspace.

Let’s talk a little bit about the role of poetics and creative community in social activism, in particular in what I call “Civil Rights 2.0,” which has remained immediately present all around us in the time leading up to this series’ publication. I’d be curious to hear some thoughts on the challenges we face in speaking and publishing across lines of race, age, privilege, social/cultural background, and sexuality within the community, vs. the dangers of remaining and producing in isolated “silos.”

We certainly do live in a time in which these issues—who publishes, what is published, who are the gatekeepers, and how do we ensure that all voices are represented—are being discussed more and more. The older guard, the major publishers, the institutions and the MFA programs, are indeed being exposed for their lack of diversity and for their conscious or unconscious endorsement of white/male/economic privilege. This also mirrors larger debate and discussion within society as a whole, and rightly so. If you look at the poetry world, though, what you find is a tension fueled by the hierarchical nature of the arts, and the fact that it’s all still subject to a market in itself. We are all in competition for our tiny little spaces, so the fighting gets fierce, and it really is a problem when vast majorities of those who are published, get positions or win awards are white and male.

The thing is: It seems that we are only now fully coming to grips with these issues, and the current state of things is a direct result of hundreds nay thousands of years of history. This means that it is more important than ever to avoid the “isolated silo” or echo chamber that only promotes itself; certainly, it was this self-congratulatory nature and dangerous lack of awareness on the part of the conceptual poets within the institutionalized avant-garde that lead to things like the travesty and racist tone-deafness of Kenneth Goldsmith’s “Michael Brown’s Body,” or Marjorie Perloff’s defense of it. Frankly, it is because the space became too white that such provocations could come into being in the first place and could find institutional support.

In the end, I think, the important steps are to take these lessons, to listen and to figure out ways to make it better. Luckily, the first step, that of recognizing there is a problem, is happening, so it becomes important to figure out what to do next. For my part, I guess, the task is to be open and receptive, and in so doing, to try to become a better ally. Just because it might seem that there will always be problematic issues of gender, sexuality, race and class in the poetry world, doesn’t mean that it can’t get so much better. In the least, I am confident that we as poets and artists will find a better way. It won’t happen overnight—we are talking about issues that have existed throughout human history—but a dedicated effort on the part of those in the community can do a great deal to right the ship; if we define the world we live in, then we can make it a better space.

[line][line]

[h3]Praise for Everybody’s Automat:[/h3]

[articlequote] Mark Gurarie’s Everybody’s Automat could be the offspring of John Ashbery and Ziggy Stardust. And yet these are poems only Gurarie can write. These poems inhabit a superhuman linguistic and psychosocial consciousness. Martians are muses, as are John Cage & planet earth, who all play supporting roles in this delightful and haunting debut collection.” – Ali Power [/articlequote]

[articlequote] The pitched quality of inventiveness in Mark Gurarie’s poems, is a worthy homage to the aleatoric musician John Cage and other musicians who inspire both the silences and contemplative notes of whimsy. The poems, like the music, however, are hitched to emotional states of being that are never distended or anemic, but curiously imaginative and responsibly resourceful to the core.” —Major Jackson[/articlequote]

[articlequote] Everybody’s Automat arrives like a hundred aliens wielding a thousand devices to process the glittering wreckage of the Anthropocene. The book’s as much of a party as it is a postmortem revealing how we spoke to each other, where we failed each other, and that we never stopped making music, even as everything went irreversibly wrong. Whether Mark Gurarie is one of us, one of them, or a little of both, I can imagine no fitter or better poet to “confront the alien that speaks of ourselves.”

—Mark Bibbins[/articlequote]

[line]

[box]

Originally of Cleveland, Ohio, Mark Gurarie currently splits time between Brooklyn, New York and Northampton, Massachusetts. He is a graduate of the New School’s MFA program, and his poems and prose have appeared in Pelt, Paper Darts, Sink Review, Everyday Genius, The Rumpus, The Literary Review, Coldfront, Publishers Weekly, Lyre Lyre and elsewhere. In 2012, the New School published Pop :: Song, the 2011 winner of its Poetry Chapbook Competition. Heco-curates the Mental Marginalia Poetry Reading Series in Brooklyn, serves as the Printed Matter Editor at Boog City and lends bass guitar and occasional vocals to psych-punk band, Galapagos Now!. In addition, he is an adjunct instructor teaching online for George Washington University, a book reviewer and a free-lance copywriter.

[/box]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]