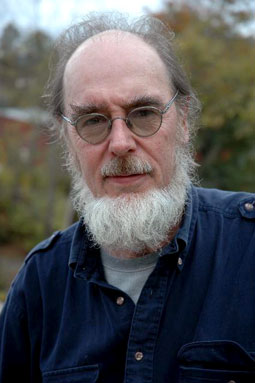

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 29 :: Doug Van Gundy on Eamon Grennan

The thing that first drew me to the poetry of Eamon Grennan was his deft handling of ekphrasis and his strong, playful sense of the music that is possible within a poem. “In The National Gallery, London” from his first book, What Light There Is still stands as perhaps the most shining exemplar of these twin traits in his work.

On my first trip to London a few years ago, I carried a photocopy of this poem with me. During my visit to the Dutch galleries that inspired Grennan, I found myself reading the poem out loud to the Rembrandts and Vermeers and Avercamps (and the handful of other patrons within earshot) in an effort to reverse-engineer the impulse that led to this chewy, musical poem.

The thing that first drew me to the poetry of Eamon Grennan was his deft handling of ekphrasis and his strong, playful sense of the music that is possible within a poem. “In The National Gallery, London” from his first book, What Light There Is still stands as perhaps the most shining exemplar of these twin traits in his work.

On my first trip to London a few years ago, I carried a photocopy of this poem with me. During my visit to the Dutch galleries that inspired Grennan, I found myself reading the poem out loud to the Rembrandts and Vermeers and Avercamps (and the handful of other patrons within earshot) in an effort to reverse-engineer the impulse that led to this chewy, musical poem.

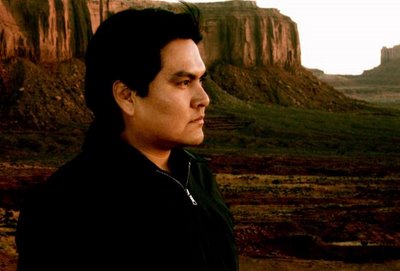

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 28 :: Roxanne Hoffman on Urayoán Noel

As an active participant of the New York poetry scene since about 2004, as a writer, performer, frequenter of open mics, writing workshop participant, reading series host and small press publisher, I like to think of myself and the other familiar faces on the local poetry circuit as a movement, a not so quiet conspiratorial insurgency, the proverbial flea buzzing in the ear of the silent sleepy majority.

As an active participant of the New York poetry scene since about 2004, as a writer, performer, frequenter of open mics, writing workshop participant, reading series host and small press publisher, I like to think of myself and the other familiar faces on the local poetry circuit as a movement, a not so quiet conspiratorial insurgency, the proverbial flea buzzing in the ear of the silent sleepy majority.

We are the defenders of free speech, free expression, freedom of the press, the right of the individual, and the power of minority opinion. Influence is what we do. We aim to move not only hearts and provoke minds with our little rants but to wake the sleepers to action. While we may make these wake-up calls with charm and style and great humor we never forget for one second it’s all about conveying that subliminal message. What’s the message? Maybe it’s just that we count simply because all human beings can create something of value and interest with a little observation, a little introspection , a little craft, the gift of vocal chords, a pen and a notebook and not much else (though many of us now write on laptops and iPads, even reading off them on the circuit.)

One of my favorite co-conspirators is Nuyorican poet Urayoán Noel. Author of three poetry collections -- Hi-Density Politics(BlazeVOX, 2010), Boringkén (Ediciones Callejón/La Tertulia, 2008), and Kool Logic/La lógica kool (Bilingual Press, 2005); Assistant Professor of English at SUNY; a Bronx Council on the Arts fellow in poetry, as well as a Ford Foundation postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, he has firmly established his foothold in the mainstream, and continues to facilitate the message. His latest project is a book-length study of Nuyorican poetry and its performance from the 1960s to the present. Not only is he making the wake-up call, he is documenting it, never forgetting he is part of a movement.POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 27 :: Annie Paradis on Prageeta Sharma

"The heritage of being alone is to transmit truth to yourself faithfully, to still the paradigm of what opposes you in the world." - ON LOVE, from Bliss to Fill

What if you have daily access to technology, but you want to be in nature, but you want to have a web presence, but you want to find truth, but you yell at your mom, but you try to meditate, but you have an active Netflix account, but you want to be THE PUREST PERSON EVER, but then you are just a human being? Yeah, me too. That's where Prageeta Sharma comes in.

I recently encountered Sharma's Bliss To Fill (Subpress Collective, 2000) a work that actively reminds one of what it is to be a person participating in her own life, but also participating in the world; a person that lives, but checks herself to see how her daily actions expand, how very threadlike it all is as they extend outward into a bigger picture.

"The heritage of being alone is to transmit truth to yourself faithfully, to still the paradigm of what opposes you in the world." - ON LOVE, from Bliss to Fill

What if you have daily access to technology, but you want to be in nature, but you want to have a web presence, but you want to find truth, but you yell at your mom, but you try to meditate, but you have an active Netflix account, but you want to be THE PUREST PERSON EVER, but then you are just a human being? Yeah, me too. That's where Prageeta Sharma comes in.

I recently encountered Sharma's Bliss To Fill (Subpress Collective, 2000) a work that actively reminds one of what it is to be a person participating in her own life, but also participating in the world; a person that lives, but checks herself to see how her daily actions expand, how very threadlike it all is as they extend outward into a bigger picture.

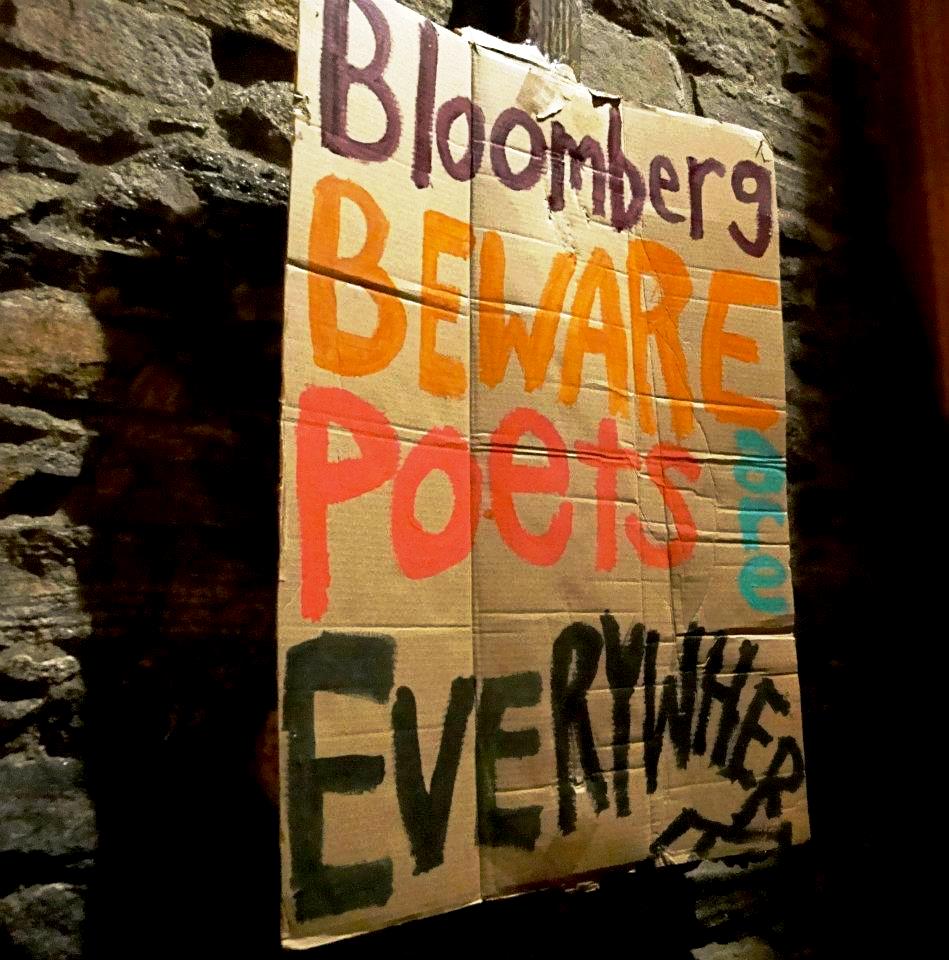

AWESOME CREATORS *NEED YOUR HELP* :: SUPPORT THE OCCUPY POETRY ANTHOLOGY!

In the introduction to the Occupy Wall Street Poetry Anthology it reads, "all movements need their poets to set the tone, to raise the questions and express the sensibility."

And so begins a tome of over 1000 pages, one that compiler Stephen Boyer originally imagined as merely a "few pages stapled together."

If you wonder how it sets the tone, you need only read the cover page, where the first words after the title are, "WE LOVE YOU."

In the introduction to the Occupy Wall Street Poetry Anthology it reads, "all movements need their poets to set the tone, to raise the questions and express the sensibility."

And so begins a tome of over 1000 pages, one that compiler Stephen Boyer originally imagined as merely a "few pages stapled together."

If you wonder how it sets the tone, you need only read the cover page, where the first words after the title are, "WE LOVE YOU."

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 26 :: Keetje Kuipers on Poets' First Books

This fall I’ll be teaching a class on first collections of poems. We’ll be talking about theme and shapeliness, the individual poems themselves as well as the way they come together to make a collection. I’m interested in first collections because I just published my own first book of poems two years ago, Beautiful in the Mouth, and I’m at work now on a second collection. Working on the second collection has made me reflect on the first book in ways that I hadn’t expected: I question the first book, and try to come up with the reasons for the way I put it together though those reasons have dissolved over time. And thinking about that first book has made me do what I probably should have done before I published it—it’s made me read lots and lots of other poets’ first books, looking in particular for the reasons that they are shaped the way they are. It’s been a wonderful journey, discovering books I hadn’t read before, and revisiting books that I had read and loved without realizing that they were a poet’s first effort. And along the way I think I’ve discovered a thing or two about first books: though they are not always the poet’s best work (and sometimes they are, which is obviously pretty sad in the long run), they are generally the poet’s most raw work, and that hunger and greed and ferocious devouring of language and emotion that happens in those first poems is a pleasure to encounter every time. First books aren’t perfect books, but they are wild ones that don’t hold back. So I’ve been spending the last few days pouring over my books of poetry, looking for first collections that I love, and there are quite a lot to choose from. In fact, I’m having trouble taking my list of thirty books and paring it down to a very reasonable ten (I’m sure that many of us would love to spend our days reading poetry, but my undergraduate students might stop coming to class if I made them read thirty books). However, I’ve got three books that I know will make the final cut, and I’d like to share a poem from each with you today.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 25 :: Ana Bozicevic on Marguerite Yourcenar

disclaimer, from Ana: "if you need a word about why I am featuring a novelist as a poetic influence; her work is poetic to the point of absurdity." et alors...

---

I, YOUrcenar.

None of my friends seem to give a shit about Marguerite Yourcenar. Sure, someone’s father read her in the 80s—probably Memoirs of Hadrian—and there was an interview in the Paris Review with her just then—just at her death. Naming her as an influence has been taken at times (dans mon cas) as an affectation. {This is supposed to be personal, so I’m making it so. But what isn’t? There’s no person, so person’s everywhere.} So this is what I can tell you about Marguerite Yourcenar & “I” (“L’être que j’appelle moi”/the person I call myself, as she puts it):

That

- it was my father who introduced me to her. And started me toward owning most of her books.

- “I” passed her novella of incestuous love, Anna Soror, around my Croatian high school like the mind-porn that it sure was.

- “I” translated parts of her Fires, a reimagining of antique myths—especially the one about Sappho—and made an offering of them to a young woman. This was my idea of courtship; should’ve read Plato’s Lysis first.

- when “I” had a blog for four years, called Quoi? L’Eternité. it was named thus after Yourcenar’s memoirs, not Rimbaud. She also introduced me to Yukio Mishima.

That’s enough now. But from a current vantage, it’s incredibly ironic that Yourcenar’s writing should have served as a queer f-to-f offering – considering the fact that though she quite likely was queer, she was also very oblique about it – what I’ve heard called “old school.” Here’s a passage from that Paris Review interview cited here without value judgment – neither for Yourcenar nor her interviewer and his “deviance:”

disclaimer, from Ana: "if you need a word about why I am featuring a novelist as a poetic influence; her work is poetic to the point of absurdity." et alors...

---

I, YOUrcenar.

None of my friends seem to give a shit about Marguerite Yourcenar. Sure, someone’s father read her in the 80s—probably Memoirs of Hadrian—and there was an interview in the Paris Review with her just then—just at her death. Naming her as an influence has been taken at times (dans mon cas) as an affectation. {This is supposed to be personal, so I’m making it so. But what isn’t? There’s no person, so person’s everywhere.} So this is what I can tell you about Marguerite Yourcenar & “I” (“L’être que j’appelle moi”/the person I call myself, as she puts it):

That

- it was my father who introduced me to her. And started me toward owning most of her books.

- “I” passed her novella of incestuous love, Anna Soror, around my Croatian high school like the mind-porn that it sure was.

- “I” translated parts of her Fires, a reimagining of antique myths—especially the one about Sappho—and made an offering of them to a young woman. This was my idea of courtship; should’ve read Plato’s Lysis first.

- when “I” had a blog for four years, called Quoi? L’Eternité. it was named thus after Yourcenar’s memoirs, not Rimbaud. She also introduced me to Yukio Mishima.

That’s enough now. But from a current vantage, it’s incredibly ironic that Yourcenar’s writing should have served as a queer f-to-f offering – considering the fact that though she quite likely was queer, she was also very oblique about it – what I’ve heard called “old school.” Here’s a passage from that Paris Review interview cited here without value judgment – neither for Yourcenar nor her interviewer and his “deviance:”

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 24 :: Elana Bell on Aracelis Girmay

It is impossible to encounter Aracelis Girmay’s work and not be moved. She writes with such an enormous heart that you cannot help being expanded in the presence of her poems. I first met Aracelis at a teaching artist training for the Community Word Project and immediately knew that my universe had shifted. Simply being in her presence and experiencing her mind is pure poetry.

Many poets are brilliant and full of heart, but I think it is a rare thing to come across a poet who is so fearless in the expression of her love and imagination. There are plenty of excerpts I could give of Aracelis’ work, but I have chosen the one below, from her first book Teeth, because before I heard this poem I didn’t know you could do that in a poem—make it that real and immediate. I recommend reading it aloud.

It is impossible to encounter Aracelis Girmay’s work and not be moved. She writes with such an enormous heart that you cannot help being expanded in the presence of her poems. I first met Aracelis at a teaching artist training for the Community Word Project and immediately knew that my universe had shifted. Simply being in her presence and experiencing her mind is pure poetry.

Many poets are brilliant and full of heart, but I think it is a rare thing to come across a poet who is so fearless in the expression of her love and imagination. There are plenty of excerpts I could give of Aracelis’ work, but I have chosen the one below, from her first book Teeth, because before I heard this poem I didn’t know you could do that in a poem—make it that real and immediate. I recommend reading it aloud.

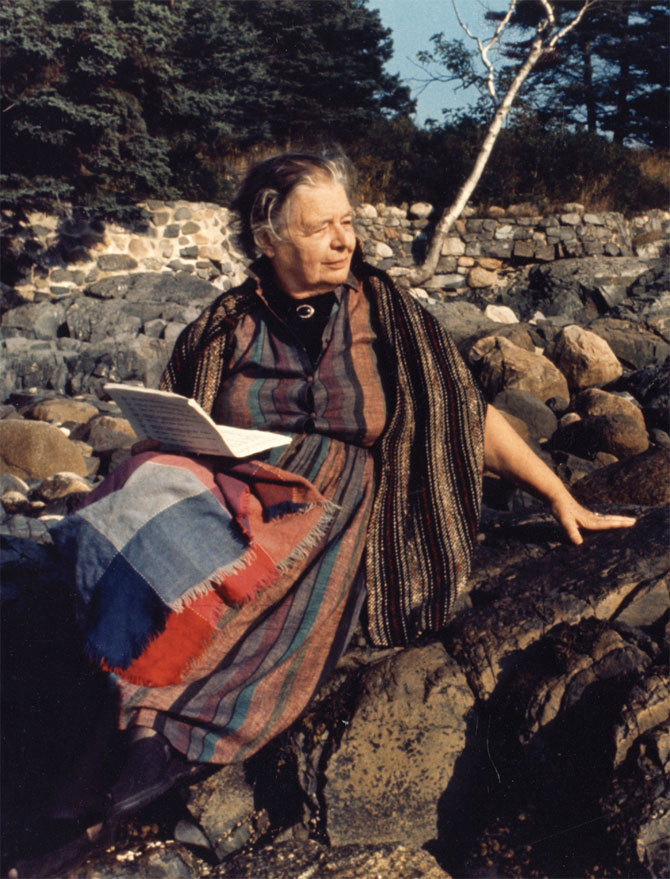

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30 : Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 23: Lauren Marie Cappello on Lorine Niedecker

The way it happens with water is like this: The beginning is unclear, maybe it happened first with rain, maybe the clouds made water from vapor or notes on dreams. Also, there is the way the water moves; it is sure of itself, searching the lowest point - steady in the breaking down of it retaining its structure to the smallest division. It asserts itself in seeking to fill its surroundings, tracing a path from one substance to the next leaving great distinction between where it is and where it is not. Lorine Niedecker’s poetry contains the essence of the water she lived by, moving across one phenomenon, seeking another in connection like a river, leaving a trail on the small portion of those places her poetry touches.

The way it happens with water is like this: The beginning is unclear, maybe it happened first with rain, maybe the clouds made water from vapor or notes on dreams. Also, there is the way the water moves; it is sure of itself, searching the lowest point - steady in the breaking down of it retaining its structure to the smallest division. It asserts itself in seeking to fill its surroundings, tracing a path from one substance to the next leaving great distinction between where it is and where it is not. Lorine Niedecker’s poetry contains the essence of the water she lived by, moving across one phenomenon, seeking another in connection like a river, leaving a trail on the small portion of those places her poetry touches.

Niedecker's work places the objects before the reader; it is in the selection of them by this poet that the scene is imbued with meaning. All else is relative. Throughout the objectivist movement, most avoided metaphor in their poetry. They took to the style of portraying the happening as it was with a feeling that in its conveyance to the audience the intended emotion would be transmitted. Niedecker’s work is a hybrid of objectivism blended with her interest in surrealism, which was contained and bubbling just below the surface. In a letter to Monroe in 1934, Lorine wrote"…the whole written with the idea of readers finding sequence for themselves, finding their own meaning whatever that may be, as spectators before abstract painting."

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 22 :: Tony Hoffman on Vicente Huidobro

I don’t recall where I first encountered the works of Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro (1893-1948)—most likely in the introduction to a collection by one of his contemporaries who came to overshadow him (Neruda or Borges). In America, at least among English-speaking poets, his work is largely forgotten; I don’t remember his name ever coming up in a conversation I didn’t initiate. But he is still well loved by people with an interest in Spanish-language poetry.

A century ago, he initiated a literary movement known as Creationism (no relation to the term’s current religious context), which holds that a poem is something new, created by the author for its own sake, not to act as commentary or to please either author or audience. He wrote of the created poem, “Nothing in the external world resembles it; it makes real what does not exist, that is to say, it turns itself into reality. It creates the wonderful and gives it a life of its own. It creates extraordinary situations that can never exist in the objective world, that they will have to exist in the poem so that they exist somewhere.”

I don’t recall where I first encountered the works of Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro (1893-1948)—most likely in the introduction to a collection by one of his contemporaries who came to overshadow him (Neruda or Borges). In America, at least among English-speaking poets, his work is largely forgotten; I don’t remember his name ever coming up in a conversation I didn’t initiate. But he is still well loved by people with an interest in Spanish-language poetry.

A century ago, he initiated a literary movement known as Creationism (no relation to the term’s current religious context), which holds that a poem is something new, created by the author for its own sake, not to act as commentary or to please either author or audience. He wrote of the created poem, “Nothing in the external world resembles it; it makes real what does not exist, that is to say, it turns itself into reality. It creates the wonderful and gives it a life of its own. It creates extraordinary situations that can never exist in the objective world, that they will have to exist in the poem so that they exist somewhere.”

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 20:: Annaliese Downey on CA Conrad

CA Conrad gave a reading at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where I study poetry, about a week ago, and afterwards the general consensus among the students in attendance was that Conrad was “insane.” We meant this affectionately and admiringly. If the motto of the Situationists, with whom Conrad has much in common, was “Be realistic—demand the impossible!”, then a suggested motto for those wishing to proceed in the spirit of Conrad might be, “Be reasonable—do what is insane!”

Conrad’s most recent book of poems, A Beautiful Marsupial Afternoon, [from Wave Books] is a guide to practical insanity. Collected within are twenty-seven “(soma)tic exercises,” instructions for the radical disruption of routine living at the individual level, and the poems resulting from those created conditions. For example: “(Soma)tic 7: Feast of the Seven Colors,” which instructs the reader to consume and surround themselves with a single particular color each day for seven days. Or “(Soma)tic 17: OIL THIS WAR!,” an exercise in making visible the linkages between waste and war. Many of the exercises are even wilder, weirder, and more uncomfortable than these, and Conrad has performed them all.

CA Conrad gave a reading at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where I study poetry, about a week ago, and afterwards the general consensus among the students in attendance was that Conrad was “insane.” We meant this affectionately and admiringly. If the motto of the Situationists, with whom Conrad has much in common, was “Be realistic—demand the impossible!”, then a suggested motto for those wishing to proceed in the spirit of Conrad might be, “Be reasonable—do what is insane!”

Conrad’s most recent book of poems, A Beautiful Marsupial Afternoon, [from Wave Books] is a guide to practical insanity. Collected within are twenty-seven “(soma)tic exercises,” instructions for the radical disruption of routine living at the individual level, and the poems resulting from those created conditions. For example: “(Soma)tic 7: Feast of the Seven Colors,” which instructs the reader to consume and surround themselves with a single particular color each day for seven days. Or “(Soma)tic 17: OIL THIS WAR!,” an exercise in making visible the linkages between waste and war. Many of the exercises are even wilder, weirder, and more uncomfortable than these, and Conrad has performed them all.