EDITORIAL : THINKING ABOUT ART AT A TIME LIKE THIS

You who are on the road Must have a code that you can live by And so become yourself Because the past is just a good bye Despite the fact that I cannot think of a single person whose life has remained untouched by

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 25 :: Ana Bozicevic on Marguerite Yourcenar

disclaimer, from Ana: "if you need a word about why I am featuring a novelist as a poetic influence; her work is poetic to the point of absurdity." et alors...

---

I, YOUrcenar.

None of my friends seem to give a shit about Marguerite Yourcenar. Sure, someone’s father read her in the 80s—probably Memoirs of Hadrian—and there was an interview in the Paris Review with her just then—just at her death. Naming her as an influence has been taken at times (dans mon cas) as an affectation. {This is supposed to be personal, so I’m making it so. But what isn’t? There’s no person, so person’s everywhere.} So this is what I can tell you about Marguerite Yourcenar & “I” (“L’être que j’appelle moi”/the person I call myself, as she puts it):

That

- it was my father who introduced me to her. And started me toward owning most of her books.

- “I” passed her novella of incestuous love, Anna Soror, around my Croatian high school like the mind-porn that it sure was.

- “I” translated parts of her Fires, a reimagining of antique myths—especially the one about Sappho—and made an offering of them to a young woman. This was my idea of courtship; should’ve read Plato’s Lysis first.

- when “I” had a blog for four years, called Quoi? L’Eternité. it was named thus after Yourcenar’s memoirs, not Rimbaud. She also introduced me to Yukio Mishima.

That’s enough now. But from a current vantage, it’s incredibly ironic that Yourcenar’s writing should have served as a queer f-to-f offering – considering the fact that though she quite likely was queer, she was also very oblique about it – what I’ve heard called “old school.” Here’s a passage from that Paris Review interview cited here without value judgment – neither for Yourcenar nor her interviewer and his “deviance:”

disclaimer, from Ana: "if you need a word about why I am featuring a novelist as a poetic influence; her work is poetic to the point of absurdity." et alors...

---

I, YOUrcenar.

None of my friends seem to give a shit about Marguerite Yourcenar. Sure, someone’s father read her in the 80s—probably Memoirs of Hadrian—and there was an interview in the Paris Review with her just then—just at her death. Naming her as an influence has been taken at times (dans mon cas) as an affectation. {This is supposed to be personal, so I’m making it so. But what isn’t? There’s no person, so person’s everywhere.} So this is what I can tell you about Marguerite Yourcenar & “I” (“L’être que j’appelle moi”/the person I call myself, as she puts it):

That

- it was my father who introduced me to her. And started me toward owning most of her books.

- “I” passed her novella of incestuous love, Anna Soror, around my Croatian high school like the mind-porn that it sure was.

- “I” translated parts of her Fires, a reimagining of antique myths—especially the one about Sappho—and made an offering of them to a young woman. This was my idea of courtship; should’ve read Plato’s Lysis first.

- when “I” had a blog for four years, called Quoi? L’Eternité. it was named thus after Yourcenar’s memoirs, not Rimbaud. She also introduced me to Yukio Mishima.

That’s enough now. But from a current vantage, it’s incredibly ironic that Yourcenar’s writing should have served as a queer f-to-f offering – considering the fact that though she quite likely was queer, she was also very oblique about it – what I’ve heard called “old school.” Here’s a passage from that Paris Review interview cited here without value judgment – neither for Yourcenar nor her interviewer and his “deviance:”

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 13:: Lancelot Runge on Philippe Soupault

An interest in surrealist game play and collaboration brought me to Philippe Soupault years ago. My current manuscript deals with the doubling or mirroring of the self, as well as reconciling mythology and contemporary pissnshit vernacular (as a shamelessly romantic)- all of which I find in Soupault. Translations lead me to where I can mishear dialogue and rewrite my favorite songs, call them my own.

Philippe Soupault est un poète français, né à Chaville le 2 août 1897, décédé à Paris le 12 mars 1990. Avec ses amis André Breton et Louis Aragon il participe à l'aventure Dada, qu'il considère comme une « table rase nécessaire », pour ensuite se tourner vers le surréalisme, dont il est un des principaux fondateurs avec André Breton. Avec ce dernier, ils ont en effet écrit le recueil de poésie Les Champs magnétiques en 1919, selon le principe novateur de l'écriture automatique. Ce recueil de poésie peut être considéré comme une des premières oeuvres surréalistes, alors que le mouvement ne se lancera vraiment qu'en 1924 avec le premier Manifeste du surréalisme d'André Breton.

An interest in surrealist game play and collaboration brought me to Philippe Soupault years ago. My current manuscript deals with the doubling or mirroring of the self, as well as reconciling mythology and contemporary pissnshit vernacular (as a shamelessly romantic)- all of which I find in Soupault. Translations lead me to where I can mishear dialogue and rewrite my favorite songs, call them my own.

Philippe Soupault est un poète français, né à Chaville le 2 août 1897, décédé à Paris le 12 mars 1990. Avec ses amis André Breton et Louis Aragon il participe à l'aventure Dada, qu'il considère comme une « table rase nécessaire », pour ensuite se tourner vers le surréalisme, dont il est un des principaux fondateurs avec André Breton. Avec ce dernier, ils ont en effet écrit le recueil de poésie Les Champs magnétiques en 1919, selon le principe novateur de l'écriture automatique. Ce recueil de poésie peut être considéré comme une des premières oeuvres surréalistes, alors que le mouvement ne se lancera vraiment qu'en 1924 avec le premier Manifeste du surréalisme d'André Breton.

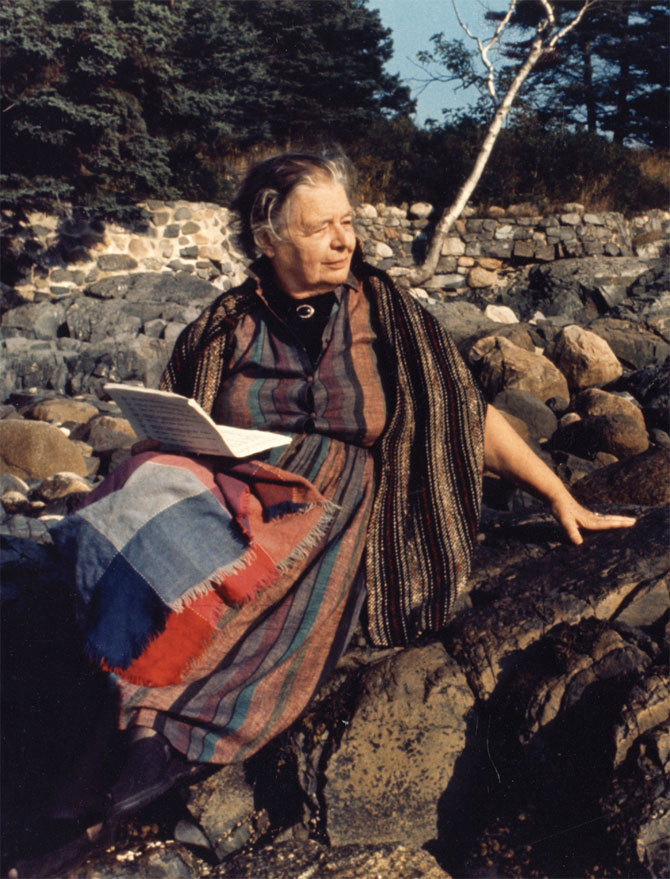

POETRY MONTH: 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 12 :: Frank Sherlock on Etel Adnan

Etel Adnan was born in 1925 in Beirut, Lebanon. Her father was a Syrian Muslim and her mother was a Greek Christian. She was raised speaking French, English, and her father taught her written Arabic. Adnan studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, Paris, University of California, Berkeley, and Harvard. She has many books of poetry and fiction published, including Paris When It's Naked, Of Cities and Women, and Sitt Marie Rose, which has been translated into over ten languages and is considered a classic of Middle Eastern literature. She also creates oils, ceramics and tapestry.

“A life spent writing has taught me to be wary of words. Those that seem clearest are often the most treacherous.” So begins Amin Malouf's In the Name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong. [Ed: free e-book/pdf at link] As words are navigated into the public sphere, to be watchful requires an interrogation of language, conscious of its make up and observant of mutations as it travels across borders and time.

Etel Adnan was born in 1925 in Beirut, Lebanon. Her father was a Syrian Muslim and her mother was a Greek Christian. She was raised speaking French, English, and her father taught her written Arabic. Adnan studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, Paris, University of California, Berkeley, and Harvard. She has many books of poetry and fiction published, including Paris When It's Naked, Of Cities and Women, and Sitt Marie Rose, which has been translated into over ten languages and is considered a classic of Middle Eastern literature. She also creates oils, ceramics and tapestry.

“A life spent writing has taught me to be wary of words. Those that seem clearest are often the most treacherous.” So begins Amin Malouf's In the Name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong. [Ed: free e-book/pdf at link] As words are navigated into the public sphere, to be watchful requires an interrogation of language, conscious of its make up and observant of mutations as it travels across borders and time.

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: Day 4 :: Tishon Woolcock on Orhan Veli Kanik

I’m going to level with you; I know nothing about Turkey and I know even less about Turkish Poetry. Luckily, I have Buké, my sole Turkish friend. Buké is tiny, smokes cigarettes, and speaks with a directness that can sometimes be mistaken for rudeness. It is she who introduced me to the Turkish poet Orhan Veli Kanik (1914-1950). I can’t speak to Kanik’s stature but, like Buké, his poetry is about as direct as a poet can get. Like the work of William Carlos Williams or, more contemporarily, Billy Collins, Kanik’s poems have been described as the kind of poetry that convinces readers they, too, can write a poem. Take, for example, “The Hill”.

I’m going to level with you; I know nothing about Turkey and I know even less about Turkish Poetry. Luckily, I have Buké, my sole Turkish friend. Buké is tiny, smokes cigarettes, and speaks with a directness that can sometimes be mistaken for rudeness. It is she who introduced me to the Turkish poet Orhan Veli Kanik (1914-1950). I can’t speak to Kanik’s stature but, like Buké, his poetry is about as direct as a poet can get. Like the work of William Carlos Williams or, more contemporarily, Billy Collins, Kanik’s poems have been described as the kind of poetry that convinces readers they, too, can write a poem. Take, for example, “The Hill”.