The OS Celebrates Women's History Month :: Pt 3 :: JP Howard, SAY/MIRROR

[box] FOR WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH 2017, I WANTED TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF THE WHOLLY ORIGINAL, CHALLENGING, SOMETIMES HEARTBREAKING WORK PUBLISHED ON THE OS BY WOMEN IN THE LAST FEW YEARS. TO FURTHER ENCOURAGE CELEBRATION, YOU ARE INVITED DURING THE MONTH OF MARCH TO PURCHASE ANY OF THE *17* BOOKS IN OUR CATALOG BY WOMEN FOR A 20% DISCOUNT (ENTERED AT CHECKOUT) USING THE CODE “THEFUTUREISFEMALE”.

.

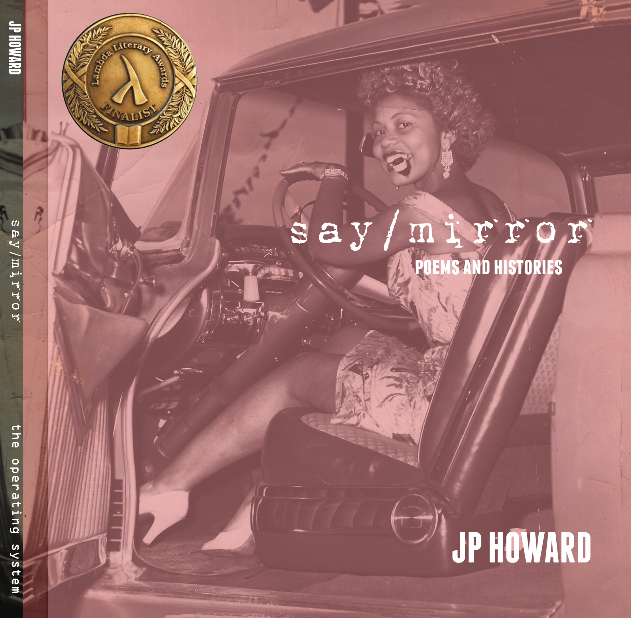

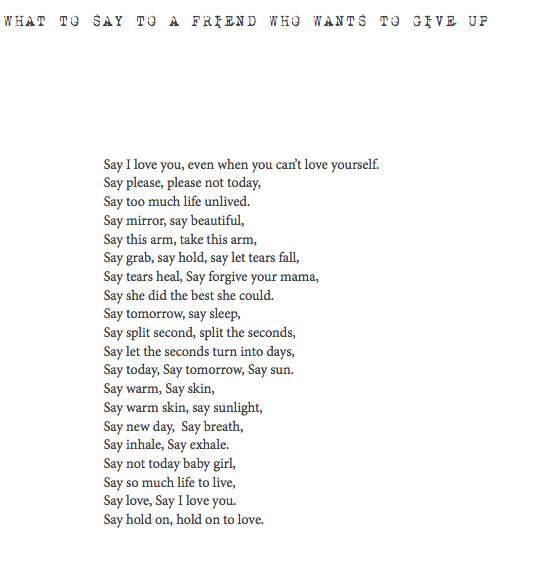

WE CONTINUE OUR CELEBRATION WITH EXCERPTS FROM JP HOWARDS’s POETRY COLLECTION, SAY/MIRROR, AS WELL AS A CONVERSATION WITH THE POET AND COMMUNITY ORGANIZER ABOUT HER PRACTICE. SAY/MIRROR WAS A FINALIST FOR THE LAMBDA LITERARY AWARDS IN 2016, WHICH JP WON AS “EMERGING POET OF THE YEAR.”

.

AND SPEAKING OF INCREDIBLE WOMEN: THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO AND INCLUDES MANY PHOTOGRAPHS OF JP’S DIVA MAMA, RUTH KING, WHO WE REMEMBER WITH ENORMOUS RESPECT.

.

ONWARD! – LYNNE DESILVA-JOHNSON[/box]

[line][line]

[line]

[line]

[line][line]

[line][line]

[box] JP Howard in conversation with Lynne DeSilva-Johnson.[/box]

Who are you?

I am a mom, a lover, a poet, a curator and nurturer of all things poetry.

Why are you a poet?

I am a poet because poetry helps me stay connected to the world and express myself. It’s the lens through which I view the world.

When did you decide you were a poet?

I was in elementary school definitely. Maybe 8 or 9 years old.

What’s a “poet”?

A poet is someone who has the courage to speak the truth as they see or experience it.

What is the role of the poet today?

The poet has many roles, currently I see the role of the poet as educator, as political activist, as lover of words and ideas.

What do you see as your cultural and social role? (in the poetry community and beyond)

My cultural role and social role is as community organizer/curator/nurturer. I think I am a natural leader, perhaps true to my Leo sign. I am most comfortable as collaborator and I work well with others to effectuate change. It’s a strength I’ve become more aware of and truly embraced these past, nearly six years, curating the Salon and working with a larger community.

Why did you decide to create a book from your work?

I’ve been writing different versions of this book my whole life.

I especially started focusing on this particular version after my mom gave me a ton of her vintage black and white modeling photos from the 1940’s and 1950’s a few years back and this really 1) mesmerized me, because some of the pictures I hadn’t seen previously and they were stunning and 2) I began to think a lot about how beauty and how the lens through which I saw my mom, growing up, in her shadow so to speak, affected me. The poems began to unfold the more I let myself explore that part of myself.

What does this particular collection of poems represent to you — as representative of your method/practice:

— as representative of your history:

The poems are definitely like a lens which allow me to look back on my childhood, but also look forward and see where I was and how both my mom and I have evolved. They are like a kaleidoscope through which fragments of my life are turning, but on the page.

— as representative of your beliefs:

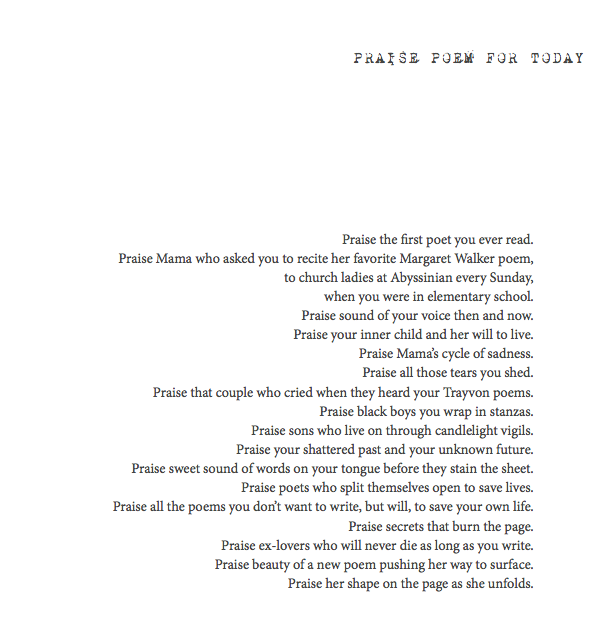

While some of the poems are a bit dark, sharing “childhood secrets” or events society tells us not to traditionally write about, I am all about being open and I view poetry as cathartic, so in that sense these poems represent my belief that writing brings us towards healing.

How is this collection representative of your mission/intentions/hopes/plans….?

The poems support my vision that poetry can tell complicated stories within a narrow frame. I also have a creative non-fiction/memoir type book that I am working on right now, so SAY/MIRROR is a small, but important way for me to explore my sometimes complicated mother/daughter relationship.

Talk a little bit about method, form, and writing process. How are the poems in this book representative of your practice and/or the history of your practice?

Some of these poems were written when I had fellowships at Cave Canem or Lambda Literary Foundation and a number were written during National Poetry Month poetry exchange groups which I am a part of, which have extended years after NaPoMo ended. I enjoy writing in form, though many of the poems in this collection loosely use form.

How do we see your development as a poet through these poems?

Some first drafts of these poems were written a number of years ago, and many of the final versions have changed with time and editing. I think poems, just like people evolve and mature with time and life experience.

What formal structures or other constrictive processes do you use in the creation of your work?

‘Diva Doll’ was initially written in the summer of 2012 in Los Angeles at a Lambda Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBT Voices in a workshop with our fierce facilitator Jewelle Gomez. There have been numerous revisions and edits in the few years since, but the overall pace and intention of the poem has not changed. The prompt for the poem was the picture of a Black Barbie doll, a collectors item, dressed in an original Bob Mackie gown that a friend had given me some years ago. Jewelle had told us before we came to California for the retreat to bring pictures that had some meaning to us and one had to be an object, so that was my object. The prompt to write about that object pushed me to write Diva Doll and also I ended up creating a poetry video collage using that doll and my mom’s black and white photos.

The poem ‘Family Secret’ was one of the most difficult poems I have ever written. I wrote the initial draft during a Cave Canem retreat in 2009. Toi Derricotte suggested a prompt, which was to write about a family secret – preferably about something we had never written about ever before. That night I went back to my room on campus and wrote Family Secret, which was literally a family memory that I had never written about previously. I remember staying up to 3 or 4am in the morning working on that poem in the dorm at the University of Pittsburgh and my two closest Cave Canem friends came out to check on me. I recall literally reading it to them and crying as I read it. I both loved and hated that poem. I had never written about that childhood memory of finding my mother, passed out and the EMT workers trying to revive her. I was really scared to turn it in for my assignment the next morning, but I did.

My friends encouraged me and it was a defining moment for me as a poet. If I could write about that HUGE family secret and still live and not explode, I figured there were other things I could also write about. Dynamic poet and Professor Ed Roberson was my instructor and gave such positive feedback on that poem. He explained it was essentially a litany, because of the repetition and form and also like a dirge, because there was a mourning for the loss of the innocence of the child and he felt it worked really well. Another student ran out of class in tears because that poem had touched something in her. It was both terrifying and cathartic to share that poem and also I experienced a bit of the same feelings when deciding whether to include it in this manuscript.

There is this “taboo” particularly in the Black community, about airing our “dirty laundry” and this poem felt a bit like that. However, the reality is that depression knows no color, race, sexual orientation or age and can affect any and everyone. I’m sure many adults have a childhood memory they may be encouraged to keep hidden, so this poem is for all those people holding in those secrets.

Let’s talk a little bit about the role of poetics and creative community in social activism, in partic- ular in what I call “Civil Rights 2.0,” what we’re going through now as this book nears publication. Can you tell me about your engagement in #blackpoetsspeakout, for instance?

I’d also be curious to hear some thoughts on the challenges we face in speaking and publishing across lines of race, age, privilege, social/cultural background, and sexuality within the creative community vs. the danger of remaining and producing in isolated silos.

The #BlackPoetsSpeakOut movement is a way for me to stay connected to the long line of poets who have been a part of justice movements. It has also been a way for me, as the Mom of two school age Black sons, and one a teenager, to express my rage, my anger, my dismay with the current state of the world, particularly continued examples of racial injustice and police brutality against young African American men and women. Every time a Black youth is killed I find myself first reacting as mother, then as a poet. This poetic movement allows me to continue to use my poetry to mourn, to protest, to wish for peace and to fight for justice.

When I think about the challenges of speaking/publishing/representing all parts of my self, I often think of the words of the late poet, Pat Parker, who said in her book Movement in Black:

“If I could take all my parts with me when I go somewhere, and not have to say to one of them, “No, you stay home tonight, you won’t be welcome,” because I’m going to an all-white party where I can be gay, but not Black. Or I’m going to a Black poetry reading, and half the poets are antihomosexual, or thousands of situations where something of what I am cannot come with me. The day all the different parts of me can come along, we would have what I would call a revolution.”

I am always aware of wearing multiple hats, I am Black lesbian, poet, partner, mother, daughter, community organizer and advocate. Like Parker, I strive to bring all parts of myself to the table when I show up; yet I also know that some parts of me are more welcome than others, depending on the forum or audience I am addressing. That being said, my goal is to not let other peoples issues, phobias and/or “isms” keep me from bringing my whole complicated poetic self to the table.

[line][line]

[box] Check out Part 1 of this series, with Caits Meissner, author of Let it Die Hungry, and Part 2, with Stephanie Heit, author of The Color She Gave Gravity.[/box]

[line]