POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 26 :: Keetje Kuipers on Poets' First Books

This fall I’ll be teaching a class on first collections of poems. We’ll be talking about theme and shapeliness, the individual poems themselves as well as the way they come together to make a collection. I’m interested in first collections because I just published my own first book of poems two years ago, Beautiful in the Mouth, and I’m at work now on a second collection. Working on the second collection has made me reflect on the first book in ways that I hadn’t expected: I question the first book, and try to come up with the reasons for the way I put it together though those reasons have dissolved over time. And thinking about that first book has made me do what I probably should have done before I published it—it’s made me read lots and lots of other poets’ first books, looking in particular for the reasons that they are shaped the way they are. It’s been a wonderful journey, discovering books I hadn’t read before, and revisiting books that I had read and loved without realizing that they were a poet’s first effort. And along the way I think I’ve discovered a thing or two about first books: though they are not always the poet’s best work (and sometimes they are, which is obviously pretty sad in the long run), they are generally the poet’s most raw work, and that hunger and greed and ferocious devouring of language and emotion that happens in those first poems is a pleasure to encounter every time. First books aren’t perfect books, but they are wild ones that don’t hold back.

So I’ve been spending the last few days pouring over my books of poetry, looking for first collections that I love, and there are quite a lot to choose from. In fact, I’m having trouble taking my list of thirty books and paring it down to a very reasonable ten (I’m sure that many of us would love to spend our days reading poetry, but my undergraduate students might stop coming to class if I made them read thirty books). However, I’ve got three books that I know will make the final cut, and I’d like to share a poem from each with you today.

The first book, Beginning with O by Olga Broumas (which won the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition in 1977), is one of the first collections of poetry I ever read. It was assigned to me in a contemporary women’s poetry class while I was an undergraduate, and when I opened it up, it blew my little undergraduate mind. Scribbled on the pages of my copy are stars and hearts and the phrases “I love this poem!” and “I don’t get what this one’s about.” Reading that book was a mixture of joy and confusion for me, and maybe that’s what all really good poetry should feel like the first time we encounter it. Here’s one with lots of red and purple stars in the margins:

The first book, Beginning with O by Olga Broumas (which won the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition in 1977), is one of the first collections of poetry I ever read. It was assigned to me in a contemporary women’s poetry class while I was an undergraduate, and when I opened it up, it blew my little undergraduate mind. Scribbled on the pages of my copy are stars and hearts and the phrases “I love this poem!” and “I don’t get what this one’s about.” Reading that book was a mixture of joy and confusion for me, and maybe that’s what all really good poetry should feel like the first time we encounter it. Here’s one with lots of red and purple stars in the margins:

“Artemis”

Let’s not have tea. White wine

eases the mind along

the slopes

of the faithful body, helps

any memory once engraved

on the twin

chromosome ribbons, emerge, tentative

from the archaeology of an excised past.

I am a woman

who understands

the necessity of an impulse whose goal or origin

still lie beyond me. I keep the goat

for more

than the pastoral reasons. I work

in silver the tongue-like forms

that curve round a throat

an arm-pit, the upper

thigh, whose significance stirs in me

like a curviform alphabet

that defies

decoding, appears

to consist of vowels, beginning with O, the O-

mega, horseshoe, the cave of sound.

What tiny fragments

survive, mangled into our language.

I am a woman committed to

a politics

of transliteration, the methodology

of a mind

stunned at the suddenly

possible shifts of meaning—for which

like amnesiacs

in a ward on fire, we must

find words

or burn.

The second book, Richard Siken’s Crush (which also won the Yale prize, this time in 2005),  exhibits the same kind of erotic hunger that Broumas’ poem above elicits in the reader. In fact, the cover of Siken’s book is a delicious shot of a stubbled upper lip that seems to be salivating over its own hand—yum! One of my mentors in graduate school, Dorianne Laux, once said that all poetry is either about sex or death, and I’ve come to believe the same thing. I’ve also come to believe that the best poetry is about sex and death together—that to have these two sides of the same coin clasped together in a single poem is the ultimate kind of poetic pleasure. Broumas does it above with her burning bodies, and Siken does it, too, in every poem in his first collection. When I bought Crush, I couldn’t stop reading it—it was a compulsive kind of turning of the pages, the way when we fall in love we can’t stop making love, though we know there will be an ending to it. Here’s the poem that gets it all started:

exhibits the same kind of erotic hunger that Broumas’ poem above elicits in the reader. In fact, the cover of Siken’s book is a delicious shot of a stubbled upper lip that seems to be salivating over its own hand—yum! One of my mentors in graduate school, Dorianne Laux, once said that all poetry is either about sex or death, and I’ve come to believe the same thing. I’ve also come to believe that the best poetry is about sex and death together—that to have these two sides of the same coin clasped together in a single poem is the ultimate kind of poetic pleasure. Broumas does it above with her burning bodies, and Siken does it, too, in every poem in his first collection. When I bought Crush, I couldn’t stop reading it—it was a compulsive kind of turning of the pages, the way when we fall in love we can’t stop making love, though we know there will be an ending to it. Here’s the poem that gets it all started:

“Scheherazade”

Tell me about the dream where we pull the bodies out of the lake

and dress them in warm clothes again.

How it was late, and no one could sleep, the horses running

until they forget that they are horses.

It’s not like a tree where the roots have to end somewhere,

it’s more like a song on a policeman’s radio,

how we rolled up the carpet so we could dance, and the days

were bright red, and every time we kissed there was another apple

to slice into pieces.

Look at the light through the windowpane. That means it’s noon, that means

we’re inconsolable.

Tell me how all this, and love too, will ruin us.

These, our bodies, possessed by light.

Tell me we’ll never get used to it.

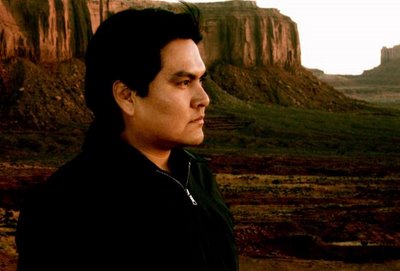

The third book is Sherwin Bitsui’s Shapeshift(which came out from the University of Arizona Press in 2003). I first encountered Bitsui’s work at a book release party that my friend, the poet Jennifer Foerster, threw for me in San Francisco when my own first collection came out. She suggested that everyone bring a book of first poems to the party so that we could read aloud from our favorites in celebration of bringing new books of poems into the world. Not only did I love this idea of celebrating my own book alongside the publication of so much other great work, but it also introduced me to a few poets I hadn’t had the chance to read before. One of those poets was Bitsui, and Jennifer was the one who presented his poems to us that night. Both Jennifer and Bitsui are Native writers, and when I read Bitsui’s poems I am struck by the seamless way that natural landscape and unnatural human landscape are so seamlessly intertwined—for instance, the way “police sirens trickle from water jars onto squash blossoms.” This line is from Bitsui’s second collection, Flood Song (Copper Canyon, 2009), and I’d like to share a poem from that book with you today. The book is a sequence of untitled poems, and the following poem, which to me is the very essence of the twisting together of life-giving force and death, is from the middle of that sequence.

The third book is Sherwin Bitsui’s Shapeshift(which came out from the University of Arizona Press in 2003). I first encountered Bitsui’s work at a book release party that my friend, the poet Jennifer Foerster, threw for me in San Francisco when my own first collection came out. She suggested that everyone bring a book of first poems to the party so that we could read aloud from our favorites in celebration of bringing new books of poems into the world. Not only did I love this idea of celebrating my own book alongside the publication of so much other great work, but it also introduced me to a few poets I hadn’t had the chance to read before. One of those poets was Bitsui, and Jennifer was the one who presented his poems to us that night. Both Jennifer and Bitsui are Native writers, and when I read Bitsui’s poems I am struck by the seamless way that natural landscape and unnatural human landscape are so seamlessly intertwined—for instance, the way “police sirens trickle from water jars onto squash blossoms.” This line is from Bitsui’s second collection, Flood Song (Copper Canyon, 2009), and I’d like to share a poem from that book with you today. The book is a sequence of untitled poems, and the following poem, which to me is the very essence of the twisting together of life-giving force and death, is from the middle of that sequence.

I carve this apple into a dove,

wrap it in a nest of boiling water.

I pinch your silences into soft whispers,

pile them on your still chest—

the marrows of turtles swirling counterclockwise inside them.

I offer a dry stem,

unfold this paper crane into a square cage.

I keep the butcher’s thumbprint’s here.

Speaking of second books, I’d like to end with a poem from mine, The Keys to the Jail (forthcoming from BOA in a year or so). This second book isn’t the most uplifting collection—the poems mostly grapple with depression, and what it feels like to blame oneself for one’s own sadness. But this poem comes at the end of the book, at the point when the speaker is starting to resurface and to grow hungry again. More than any of the other poems in the new collection, the feeling of this one takes me back to my first book: it’s original hunger, it’s raw appetite. There is a kind of quiet ecstasy that I wanted to capture in this poem—the joy of coming alive again after a long but temporary death—that feels like the kind of twining together I’ve been talking about in the other poems I’ve shared with you today.

This poem originally appeared in Cave Wall, which is a delicious little literary magazine out of North Carolina. It’s got a classy, old-school, single-tone cover with gorgeous block prints, and inside it’s just poem after poem after juicy poem. It’s a little magazine that I’m in love with—in fact, I’m requiring my poetry students to subscribe (at a special Poetry Month discount price) in the fall. It’s nice to know what it feels like to hold a piece of art in your hands.

Something with a Heart in It

I was as beautiful as I was ever going to be.

The man who loved me

liked to take my face in his hands

and remark on it.

When the doctor touched my breasts,

she seemed pleased

even with their fibrous underbellies.

I never recognized

my happiness. Not in the bouquets

of cherry blossoms

sold on Clement, tied with green plastic

ribbon. Not in the winning

dog, Tell You Why, I half-heartedly

bet on at the races.

Instead, there was this little world

I’d made.

And I celebrate it now

in the seagulls,

the way they rise and fall, tossing on the wind’s

pale confetti.

—–

Keetje Kuipers is a native of the Northwest. She earned her B.A. at Swarthmore College and her M.F.A. at the University of Oregon, and was most recently a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University. Keetje is the 2011-2012 Emerging Writer Lecturer at Gettysburg College. In 2007 Keetje was the Margery Davis Boyden Wilderness Writing Resident. She used the residency to complete work on her book Beautiful in the Mouth, which was awarded the 2009 A. Poulin, Jr. Poetry Prize and was published in 2010 by BOA Editions.